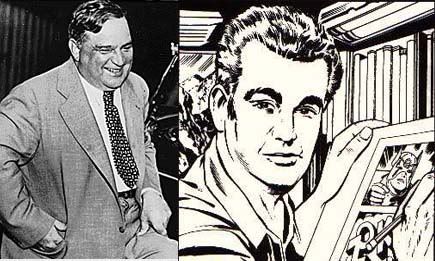

Once upon a time we had a real mayor of the people in New York. Talk about a lineage that KVer's would love, Fiorello's dad was Italian and his mom was Jewish.

from Wikipedia:

Fiorello Henry LaGuardia (born Fiorello Enrico LaGuardia; December 11, 1882 – September 20, 1947) (often spelled La Guardia [la 'gwardja]) was the Mayor of New York for three terms from 1934 to 1945. He was popularly known as "the Little Flower," the translation of his Italian first name, Fiorello [fjo'rɛl:o], or perhaps a reference to his short stature. A Republican, he was a popular mayor and a strong supporter of the New Deal. LaGuardia led New York's recovery during the Great Depression and became a national figure, serving as President Roosevelt's director of civilian defense during the run-up to the United States joining the Second World War.

LaGuardia was born in the Bronx to an Italian lapsed-Catholic father, Achille La Guardia, from Cerignola, and an Italian mother of Jewish origin from Trieste, Irene Coen Luzzato; he was raised an Episcopalian. His middle name Enrico was changed to Henry (the English form of Enrico) when he was a child. He spent most of his childhood in Prescott, Arizona. The family moved to his mother's hometown after his father was discharged from his bandmaster position in the U.S. Army in 1898. LaGuardia served in U.S. consulates in Budapest, Trieste, and Fiume (1901–1906). Fiorello returned to the U.S. to continue his education at New York University. During this time, he worked for New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty for Children and as a translator for the U.S. Immigration Service at Ellis Island (1907–1910).

He became the Deputy Attorney General of New York in 1914. In 1916 he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, where he developed a reputation as a fiery and devoted reformer. In Congress, LaGuardia represented then-Italian East Harlem and was a member of the House of Representatives almost continuously until 1933. According to his biographer-historian Howard Zinn, there were two brief interruptions, one to fly with U.S. forces in Italy during World War I, and the other to serve during 1920 and 1921 as president of the New York City Board of Alderman.[1]

Zinn wrote that LaGuardia represented "the conscience of the twenties":

As Democrats and Republicans cavorted like rehearsed wrestlers in the center of the political ring, LaGuardia stalked the front rows and bellowed for real action. While Ku Klux Klan membership reached the millions and Congress tried to legislate the nation toward racial 'purity,' LaGuardia demanded that immigration bars be let down to Italians, Jews, and others. When self-styled patriots sought to make the Caribbean an American lake, LaGuardia called to remove the marines from Nicaragua. Above the clatter of ticker-tape machines sounding their jubilant message, LaGuardia tried to tell the nation about striking miners in Pennsylvania.

Zinn continued (p. viii): "The progressives of the twenties and early thirties, however, did not merely complain; they offered remedies, again and again.... Most of the New Deal legislation was anticipated by LaGuardia... and others both before and after the 1929 crash, so that, when Franklin D. Roosevelt took his oath of office, a great deal of initial work had already been done."

LaGuardia briefly served in the armed forces (1917-1919), commanding a unit of the United States Army Air Service on the Italian/Austrian front in World War I, rising to the rank of major.

In 1921 his wife died of tuberculosis. LaGuardia, having nursed her through the 17-month ordeal, grew depressed, and turned to alcohol, spending most of the year following her death on an alcoholic binge. He recovered and became a teetotaler.

"Fio" LaGuardia (as his close family and friends called him) ran for, and won, a seat in Congress again in 1922 and served in House until March 3, 1933. Extending his record as a reformer, LaGuardia sponsored labor legislation and railed against immigration quotas. In 1929 he ran for mayor of New York, but was overwhelmingly defeated by the incumbent Jimmy Walker. In 1932, along with Sen. George Norris (R-NE), Rep. LaGuardia sponsored the pro-union Norris-LaGuardia Act. In 1932 he was defeated for re-election to the House by James J. Lanzetta, the Democratic candidate (the year 1932 was not a good one for people running on the Republican ticket, and additionally, the 20th Congressional district was shifting from a Jewish and Italian-American population to a Puerto Rican population).

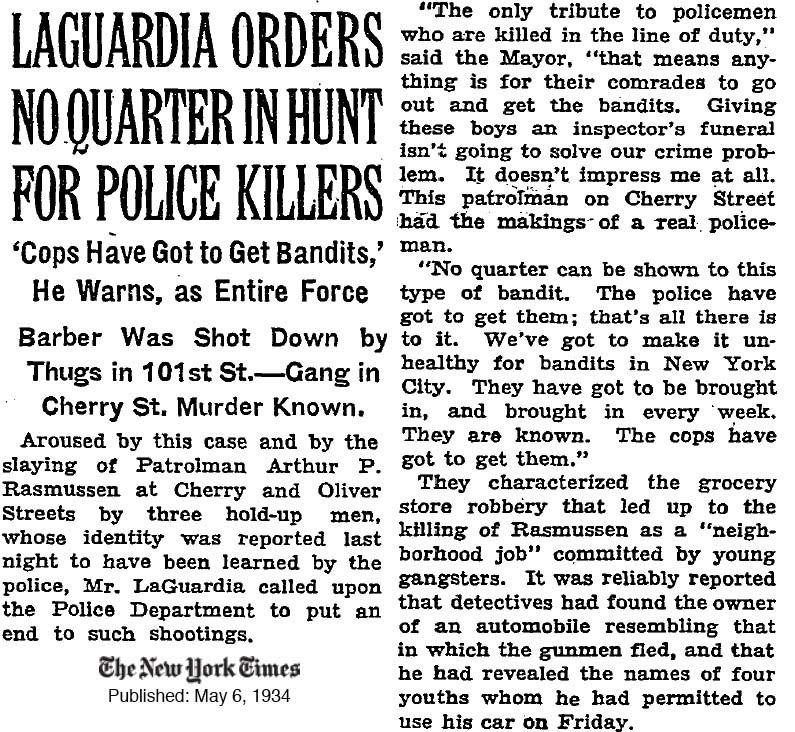

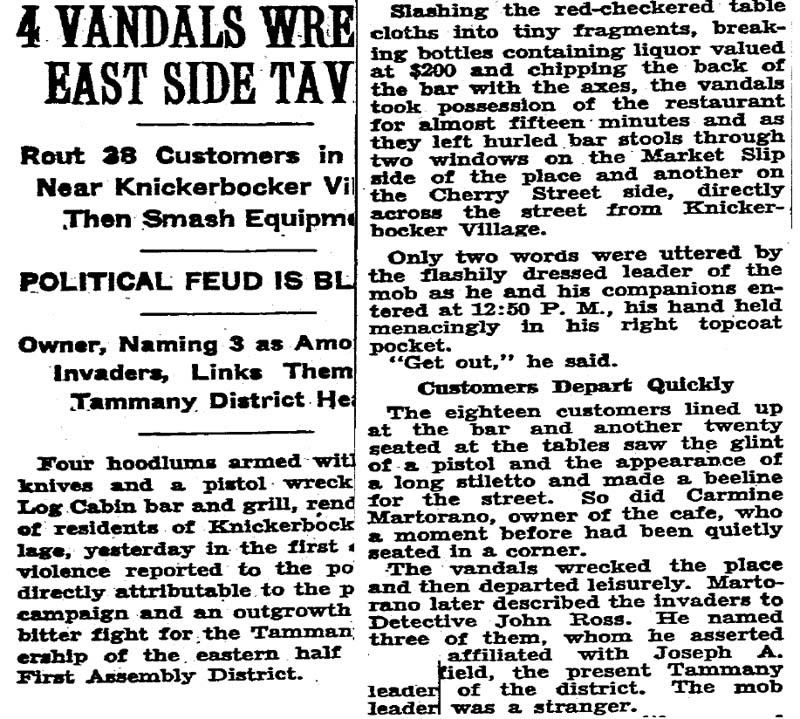

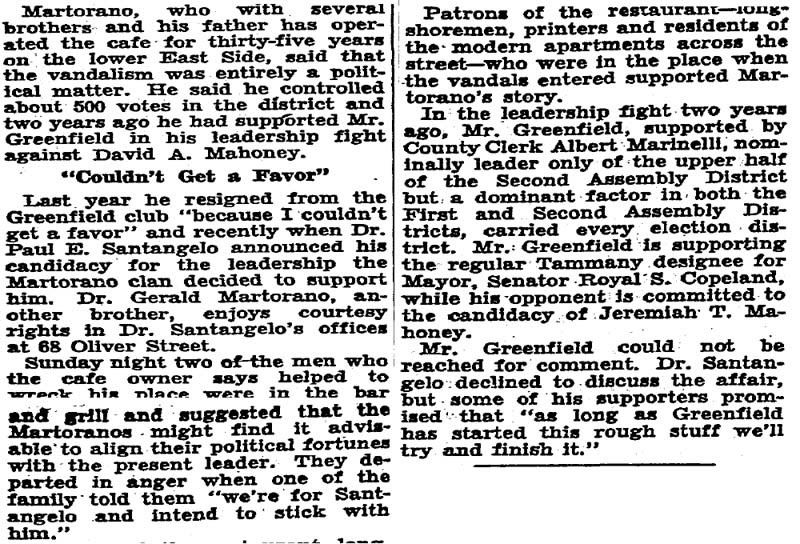

Being of Italian descent and growing up in a time when crime and criminals were prevalent in the Bronx, LaGuardia loathed the gangsters who brought a negative stereotype and shame to the Italian community; the "Little Flower" had an even greater dislike for organized crime members. When he was elected to his first term in 1933, the first thing he did after being sworn in was to pick up the phone and order the chief of police to arrest mob boss Lucky Luciano on whatever charges could be laid upon him. LaGuardia then went after the gangsters with a vengeance, stating in a radio address to the people of New York in his high-pitched, squeaky voice, "Let's drive the bums out of town." In 1934, LaGuardia's next move was a search-and-destroy mission on mob boss Frank Costello's slot machines, which LaGuardia executed with a gusto, rounding up thousands of the "one armed bandits," swinging a sledgehammer and dumping them off a barge into the water for the newspapers and media. In 1936, LaGuardia had special prosecutor Thomas E. Dewey, a future Republican presidential candidate, single out Lucky Luciano for prosecution. Dewey managed to lead a successful investigation into Luciano's lucrative prostitution operation and indict him, eventually sending Luciano to jail on a 30-50 year sentence.

LaGuardia was hardly an orthodox Republican. He also ran as the nominee of the American Labor Party, a union-dominated anti-Tammany grouping that also ran FDR for President from 1936 onward. LaGuardia also supported Roosevelt, chairing the Independent Committee for Roosevelt and Wallace with Nebraska Senator George Norris during the 1940 presidential election.

LaGuardia was the city's first Italian-American mayor, but was not a typical Italian New Yorker. He was a Republican Episcopalian who had grown up in Arizona, and had an Istrian Jewish mother and a Roman Catholic-turned-atheist Italian father. He reportedly spoke seven languages, including Hebrew, Croatian, German, Hungarian, Italian, and Yiddish.

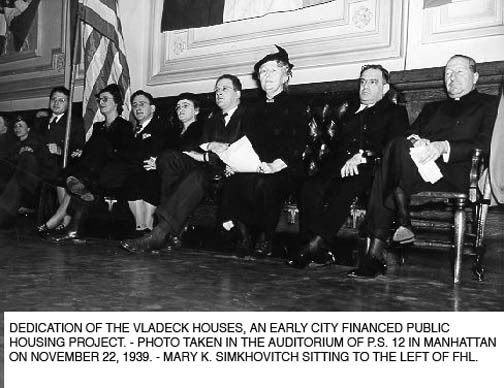

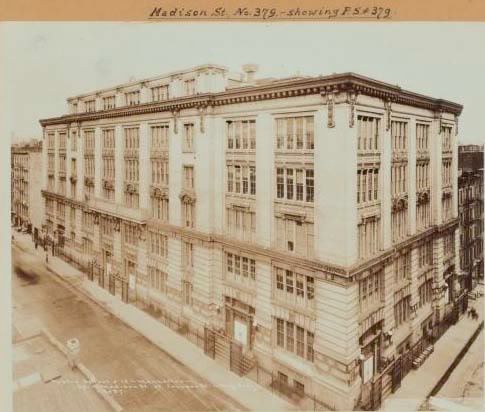

LaGuardia's fans credit him for, among other things, restoring the economic lifeblood of New York City during and after the Great Depression. His massive public works programs administered by his friend Parks Commissioner Robert Moses employed thousands of unemployed New Yorkers, and his constant lobbying for federal government funds allowed New York to develop its economic infrastructure. He was well known for reading the newspaper comics on WNYC radio during a 1945 newspaper strike, and pushing to have a commercial airport (Floyd Bennett Field, and later LaGuardia Airport) within city limits. Responding to popular disdain for the sometimes corrupt City Council, LaGuardia successfully proposed a reformed 1938 City Charter that created a powerful new New York City Board of Estimate, similar to a corporate board of directors.

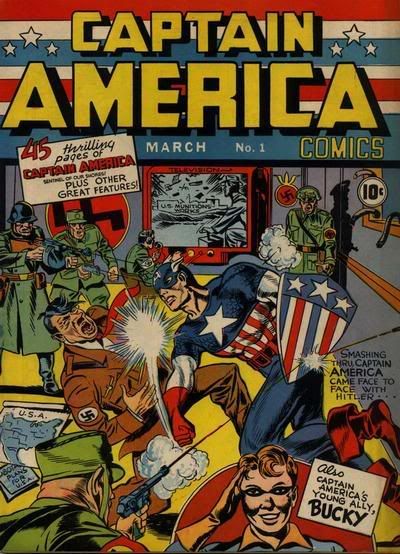

He was an outspoken and early critic of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi regime. In a public address as early as 1934, LaGuardia warned, "Part of Hitler’s program is the complete annihilation of the Jews in Germany." In 1937, speaking before the Women’s Division of the American Jewish Congress, LaGuardia called for the creation of a special pavilion at the upcoming New York World’s Fair "a chamber of horrors" for "that brown-shirted fanatic."

In 1940, included among the many interns to serve in the city government was David Rockefeller, who became his secretary for eighteen months in what is known as a "dollar a year" public service position. Although LaGuardia was took pains to point out to the press that Rockefeller was only one of 60 interns, Rockefeller's working space turned out to be the vacant office of the deputy mayor.

In 1941, during the run-up to American involvement in the Second World War, President Roosevelt appointed LaGuardia as the first director of the new Office of Civilian Defense (OCD). The OCD was responsible for preparing for the protection of the civilian population in case America was attacked. It was also responsible for programs to maintain public morale, promote volunteer service, and co-ordinate other federal departments to ensure they were serving the needs of a country in war. LaGuardia had remained Mayor of New York during this appointment, but after the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 he was succeeded at the OCD by a full-time director, James M. Landis.

According to Try and Stop Me by Bennett Cerf, LaGuardia often officiated in municipal court. He handled routine misdemeanor cases, including, as Cerf wrote, a man who had stolen a loaf of bread for his starving family. LaGuardia still insisted on levying the fine of ten dollars. Then he said "I'm fining everyone in this courtroom fifty cents for living in a city where a man has to steal bread in order to eat!" He passed his hat and gave the fines to the defendant, who left the court with $47.50.[2]

LaGuardia was the director general for the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) in 1946.

LaGuardia loved music and conducting, and was famous for spontaneously conducting professional and student orchestras that he visited. He once said that the "most hopeful accomplishment" of his long administration as mayor was the creation of the High School of Music & Art in 1936, now the Fiorello H. LaGuardia High School of Music & Art and Performing Arts.[3] In addition to LaGuardia High School, a number of other institutions are also named for him, including LaGuardia Community College. He was the subject of the Pulitzer Prize-winning Broadway musical Fiorello!. He was a member of Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia music fraternity.

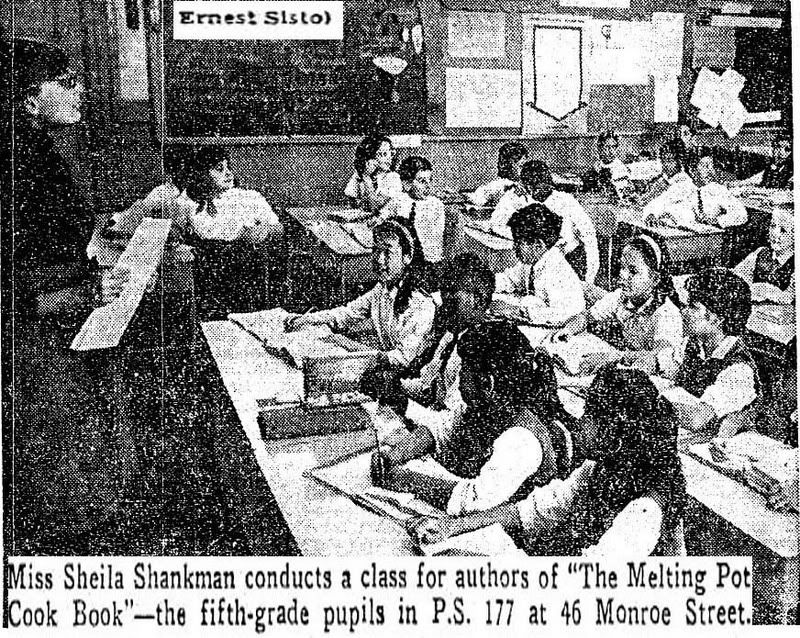

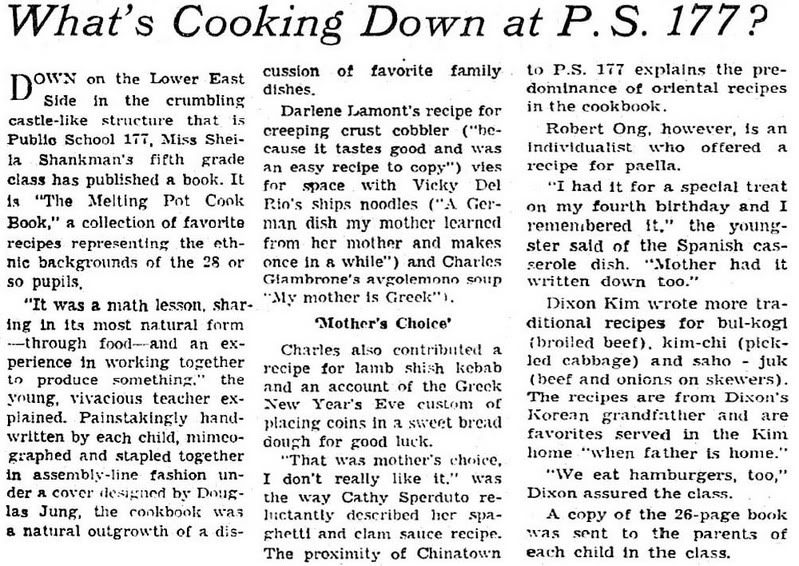

He died at his 5020 Goodridge Avenue home, in the Riverdale section of the Bronx, of pancreatic cancer at the age of 64 and is interred at Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx.