From the Sarasota Patch

By Marc Maturo

Joe Bruno is perhaps one of the most direct people I know. When he speaks his mind, you know precisely where he stands – just as he has done for many years in epistolary fashion with a local newspaper columnist.

This should not be surprising perhaps for a transplanted New Yorker who, he clearly recalls, was ripped from the outset for his accent. Ripped or not, the former parking lot owner and writer hosted his own radio show—"In the Know with Joltin' Joe -- on WQSA (1220) from 4 p.m.-6 p.m. each day. He did that for about two years without a co-host. "That wasn't easy -- and I can talk," Joe noted, with an obvious but unintended understatement.

One of his early guests was an 11- or 12-year-old Russian tennis player, Maria Sharapova, who was taking boxing lessons for her conditioning on the advice of Floridian Harold Wilen.

Bruno – who served in Vietnam aboard the USS Constellation in the Gulf of Tonkin -- also sold commercial real estate as well (bars and restaurants) and kept writing, kept writing and kept writing.

Bruno's latest novel, Find Big Fat Fanny Fast, is the second he has had published; the other is Angel of Death.

So, Joe, can we now call you a novelist? To which the 63-year-old Atkins diet proponent – he works out five days a week at Lifestyle Gym – bellowed in his patented staccato-like manner: "Novelist! I've been a novelist for 30 years! I had two in the 80's, but didn't get published; you don't have to be published to be a writer."

Bruno relocated to Sarasota in 1995 following the breakup of his marriage to be near his children Nancy Cason, an associate at the Ringling Blvd. law firm of Syprett, Mishad, Resnick and Lieb; and his son Joe Jr., a preacher with the Church of Christ in Charlotte, N.C. – "Can you imagine this!" Bruno the Elder exclaims, himself in amazement.

Bruno had met a gal named Jeanie in 1988 and, lo and behold, they formally tied the knot this past April.

"Now they can say, Joe Bruno finally did the right thing," Bruno pontificated.

But, Bruno still feels like an outsider. "Accepted? Yeah – no," he says. "Not really. When I sold bars and restaurants I was out almost every night. What abuse I took. When you're from up north, especially a New Yorker, you're an outsider. I hide in my house. I'm the only guy in Sarasota with a baseball bat near every door."

On a sign attached to his front door are various messages. Among them:

* Don't knock unless you are leaving a package.

* If you knock, I won't be very happy.

* If you want a friend, get a dog.

"Even the post office is afraid to knock on my door. Let's face it I'm a fish out of water. I've been here 15 years and never met anyone from New York City … just one guy from Brooklyn. I have one good friend and he's not from Sarasota, he's from Scotland. He lives outside London now. He comes here on a visa; comes after Thanksgiving and stays six months. He was the best man at my wedding and I can't understand a word he says."

What then, would keep Joe the Patriot here in Florida despite the drawbacks, perceived or otherwise.

"Where am I going to go?" asks the Patriot, who spent his pre-Sarasota years in New York at Knickerbocker Village on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. "It's like paradise here. I have a house with a pool. I'm 63 now, can't drink every night and my wife works. I have four dogs, one cat and a bird. We have to take separate vacations because someone has to watch the animals.

"They're going to have to carry me out of this house in a box. If I was younger, I'd be back in New York. But if I went back, it would cost me $4,000 a month for two bedrooms. And at my age, No. 1, the cold is no good for me; No. 2 it's paradise (here). The only problem is, all my friends, my real friends are in New York. "

Although he's "still a maniac in a cage," – his own words – Bruno keeps pounding the keyboard, producing 800-word essays on American mobsters, dating back to 1825. One book of excerpts is his next project, and then two more volumes will focus on New York. "Another book I'll be doing will be on 'rats', informers -- you know, like Sammy The Bull (Gravano)," Bruno rattles on, relentlessly. "I'm tied up with book deals for the next five years, and I have a screenplay that will be turned into a novel."

And with that, abruptly, the stream of consciousness ends. "Got enough? If you need more, let me know."

The print version of Find Big Fat Fanny Fast is available here

Tuesday, December 28, 2010

Monday, December 27, 2010

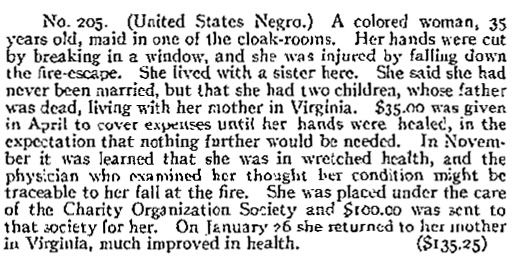

Triangle Factory Fire Aftermath

The above is from the Red Cross report on the distribution of aid to triangle victims and families.

I recently learned that many of the survivors of the fire were not listed and that there were many black people who worked at the factory in janitorial jobs.

I recently learned that many of the survivors of the fire were not listed and that there were many black people who worked at the factory in janitorial jobs.

Sunday, December 26, 2010

Christmas 1921: Hamilton House Toy and Clothing Giveaway

Christmas Coulter Hamilton 1921

The story mentions Major Wiliam Francis Deegan It also says that the 79th Street Neighborhood House, the Lincoln House, and Hamilton House were branches of the Henry Street Settlement. The Lincoln Houe on west 63rd Street was for the "colored"

The story mentions Major Wiliam Francis Deegan It also says that the 79th Street Neighborhood House, the Lincoln House, and Hamilton House were branches of the Henry Street Settlement. The Lincoln Houe on west 63rd Street was for the "colored"

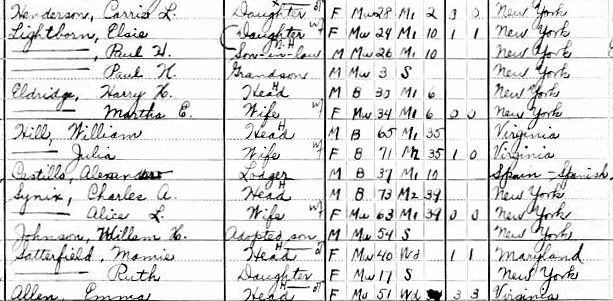

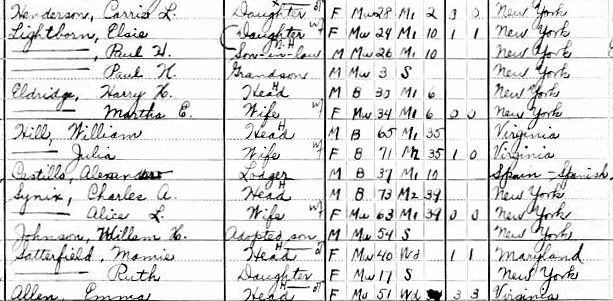

Was This Harry Eldredge?

Below, a portion of the census for the above building in 1910. Most of the inhabitants were either black or listed as mixed white.

I tried to find the Harry Eldredge who worked at the Triangle Factory in the 1910 census. Maybe it was the Harry who lived at the above address with his wife Martha

(mixed). Harry's job was listed as a coachman for a private family.

Saturday, December 25, 2010

The Triangle Factory Fire Scandal 1979 Film

A few minutes of the movie's opening. A hard to find film and not really worth the premium price it commands. I found it useful for giving a basic understanding of the events for kids although I edit certain scenes. A movie goof

At one point one of the ladies working in the factory makes reference to having seen Charlie Chaplin. This film is set in 1911; Chaplin didn't make his first film until 1914 and would have been completely unknown in America in 1911.Tovah Feldshuh, one of the stars of the film, will be the narrator of a 2011 HBO documentary on the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire.

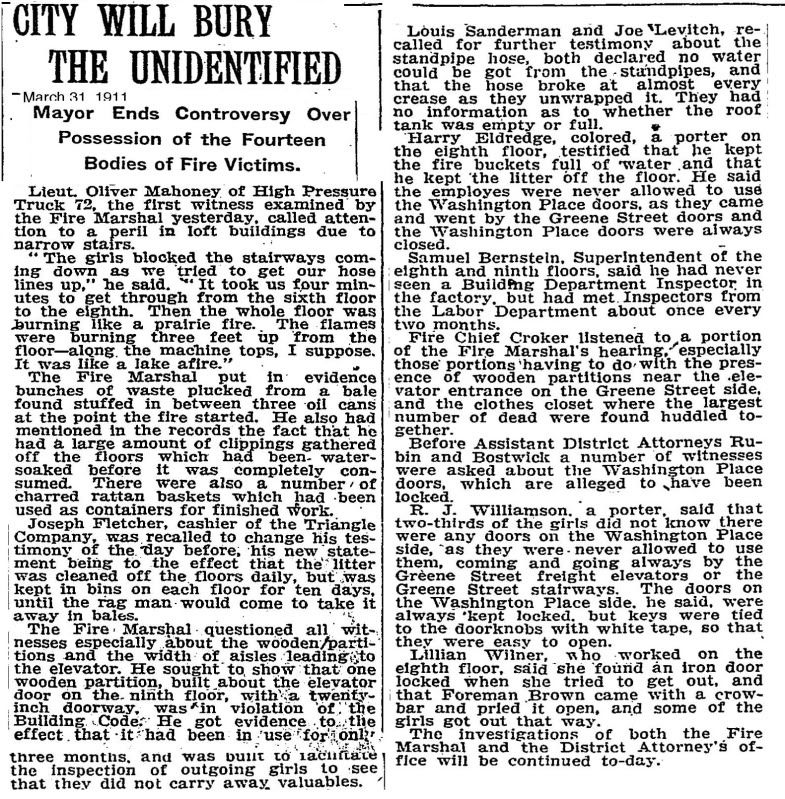

Harry Eldredge Testifies At Triangle Hearing

This is new to me, that there were black people employed at the factory. It's possible that Eldredge wasn't working that day or left earlier since he isn't listed as a survivor.

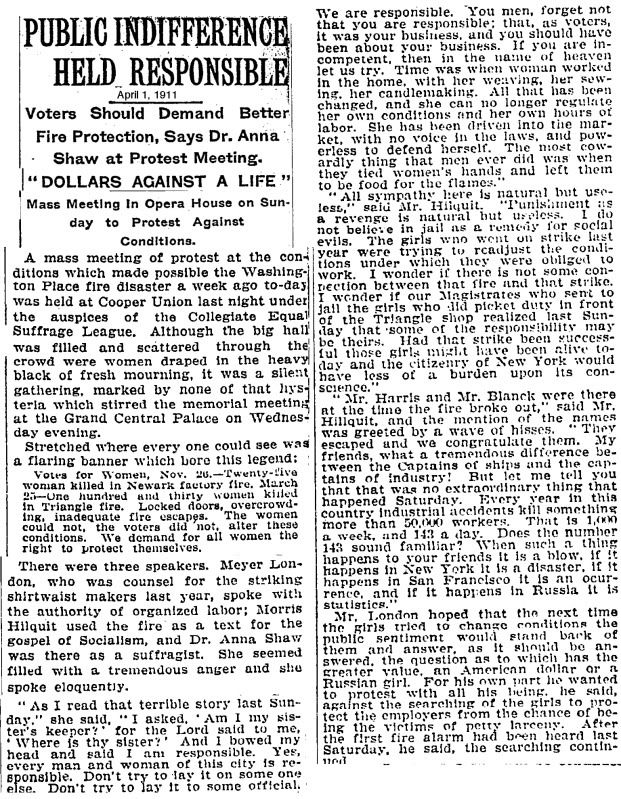

Anna Howard Shaw "Day"

Anna Howard Shaw (February 14, 1847 – July 2, 1919) was a leader of the women's suffrage movement in the United States. She was also a physician and the first ordained female Methodist minister in the United States.

Shaw was born at Newcastle-on-Tyne, England, but was brought to the United States as a small child. Her family initially lived in Lawrence, Massachusetts, but soon moved to the Michigan frontier where they lived in a floorless log cabin in the wilderness. After the Civil War, Shaw, now a teenager, moved in with her sister in Big Rapids, Michigan. Inspired by the sermons of a Unitarian minister, Marianna Thompson, Shaw decided to pursue a religious life. Shaw delivered her first sermon in 1870. Soon she was preaching in towns throughout the area.

Shaw entered Albion College, a Methodist school in Albion, Michigan, in 1873. From there she went on to Boston University School of Theology where she graduated in 1876. She was the only woman in her graduating class. She paid her own expenses through college and university by preaching and lecturing. After serving as a minister at Methodist churches in Hingham and East Dennis, Massachusetts, Shaw was ordained by the Methodist Protestant Church in 1880—the first ordination of a woman by that church. She received an M.D. from Boston University in 1886. During her time in medical school, Shaw became an outspoken advocate of political rights for women. She was also active in the temperance movement and served as national superintendent of franchise for the Woman's Christian Temperance Union from 1886 to 1892.

Shaw became a confidant of Susan B. Anthony in the woman's suffrage movement, leading the National American Woman Suffrage Association from 1904 to 1915. During her tenure as president, the organization renewed efforts to lobby for a national constitutional amendment granting women the right to vote. Due to growing factionalism within the organization, Shaw decided not to run for reelection in 1915. She was succeeded by Carrie Chapman Catt.

During World War I, Shaw was head of the Women's Committee of the United States Council of National Defense, for which she became the first woman to earn the Distinguished Service Medal.

Shaw died of pneumonia at her home in Moylan, Pennsylvania at the age of seventy-two, only a few months before Congress ratified the Nineteenth Amendment to the US Constitution.

In 2000, she was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame. Anna Howard Shaw Day is celebrated on her birthday, February 14th, (or the nearest Sunday by an act of the United Methodist Church or by some feminists as an alternative to Valentine's Day. The NBC show 30 Rock referenced the holiday as an alternative to Valentine's Day in the episode "Anna Howard Shaw Day".

Meyer London: 279 East Broadway

Meyer London (1871—1926) was an American politician from New York City. He is best remembered as one of only two members of the Socialist Party of America elected to the United States Congress.

Meyer London was born in Kalvarija, Lithuania (then part of the Russian Empire) on December 29, 1871. Meyer's father, Efraim London, was a former Talmudic scholar who had become politically revolutionary and philosophically agnostic, while his mother had remained a devotee of Judaism. His father had established himself as a grain merchant in Zenkov, a small town located in Poltava province of the Ukraine, but his financial situation was poor and in 1888 his father emigrated with Meyer's younger brother to the United States, leaving Meyer behind.

Meyer attended Cheder, a traditional Jewish primary school in which he learned Hebrew, before entering Russian-language schools to begin his secular education.[2] In 1891, when Meyer was 20, the family decided to follow his father to America so Meyer terminated his studies and departed for New York City, taking up residence in the city's largely Jewish Lower East Side.

In America, Meyer's father had become a commercial printer, doing jobs in the Yiddish, Russian, and English languages and publishing his own radical weekly called Morgenstern. Efraim London's shop was a hub of activity, bringing together Jewish radical intellectuals from throughout the city, many of whom met and influenced the printer's son with their ideas.

Meyer earned money as a tutor, taking on pupils at irregular hours and teaching literature and other topics. He later obtained a job as a librarian, a position which allowed him sufficient time to read about history and politics and to study law in his free time. Meyer also frequented radical meetings, gradually developing proficiency as a public speaker and participant in public debates.

In 1896, London was accepted to the law school of New York University, attending most of his classes at night. He completed the program and was admitted to the New York state bar in 1898, becoming a labor lawyer, taking on cases which fought injunctions or defending the rights of tenants against the transgressions of landlords. London did not handle criminal cases, but rather limited himself to matter of civil law.

In 1898, London ran for New York Assembly in the old 4th Assembly District, as the candidate of the Social Democratic Party of America, successor organization of Debs' Social Democracy.

London was active in the 1910 New York Cloakmakers Strike, during which the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union (ILGWU) brought out 50,000 in a successful struggle for higher wages and better work conditions against their employers. In his capacity as counsel for the ILGWU, London drew up and published a communique in the name of the strike committee.[10] In this manifesto, London declared:

"We charge the employers with ruining the great trade built up by the industrious immigrants. We charge them with having corrupted the morale of thousands employed in the cloak trade.... Treachery, slavishness and espionage are encouraged by the employers as great virtues of the cloakmakers. This general strike is greater than any union. It is an irresistible movement of the people. It is a protest against conditions that can no longer be tolerated. This is the first great attempt to regulate conditions in the trade, to do away with that anarchy and chaos which keeps some of the men working sixteen hours a day during the hottest months of the year while thousands of others have no employment whatever.... We appeal to the people of America to assist us in our struggle."

London argued against an injunction issued against the strikers before the New York Supreme Court en route to a victory of the strikers after a labor action lasting the better part of two months.

In January 1916, London was joined by Socialist Party leaders James Maurer and Morris Hillquit in a meeting with President Woodrow Wilson trying to forestall American entry into World War I.

London's place in the cloakmakers' strike made him one of the best-known public faces of the Socialist Party in New York City and over the course of three runs for Congress he gradually constructed a winning coalition, emerging victorious despite the violence and fraud practiced by the campaign of his Tammany Hall-supported Democratic opponent in the election of 1914. London thus became the second Socialist elected to Congress, following Wisconsin's Victor Berger.

As a Congressman, Meyer London was one of 50 representatives and six senators to vote against entry into World War I. Once America was at war, however, London felt obliged to support the nation's efforts in the conflict. He strongly opposed the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918, which made criticism of the president or the war a crime. These actions angered his constituency, London said, "I wonder whether I am to be punished for having had the courage to vote against the war or for standing by my country’s decision when it chose war."

The Aftermath Of The Triangle Fire: Shaw, London and Hillquit Speak Out

an excerpt from the full nytimes' article

It would be great if the Meyer London School, PS 2 on Henry Street and the Anna Howard Shaw School, aka the Children's Workshop/East Village Community School, on East 12th Street, were involved with the 100th anniversary of the triangle shirtwaist fire

It would be great if the Meyer London School, PS 2 on Henry Street and the Anna Howard Shaw School, aka the Children's Workshop/East Village Community School, on East 12th Street, were involved with the 100th anniversary of the triangle shirtwaist fire

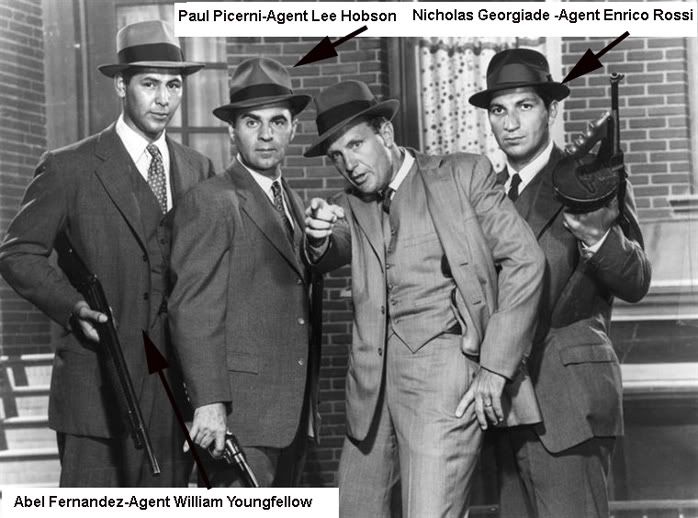

Nicholas Georgiade: A Greek Portraying An Italian

I was hoping that Nick had links to the Greek immigrant community in the Fourth Ward. His roots, however, are in Queens.

Nicholas Georgiade (born May 25, 1933, New York City) is an American actor of television and film.

He is a veteran of 37 movies and television programs. His television career began on the December 11, 1958 Playhouse 90 episode titled Seven Against the Wall with Warren Oates, Tige Andrews, and Paul Lambert. Georgiade followed this with playing Tommy on the January 23, 1960 Westinghouse Desilu Playhouse episode Meeting at Appalachia which included Cameron Mitchell and Jack Warden. Other appearances on such notable programs as Hawaiian Eye, Hawaii Five-O, Batman, I Spy, Kojak, and The Rockford Files. He had a recurring role from 1959—1963 as Agent Enrico Rossi on 105 episodes of the 1959 hit program, The Untouchables. Agent Enrico Rossi, the lone Italian member of the elite law enforcement squad. Georgiade had played a hood in the pilot episode for the show but the producers liked his presence and cast him as a regular member of the good guys once the show was picked up as a weekly series. Has lived in Las Vegas with his wife for many years and still does some occasional stage and film work

The Untouchables And Almost KV

Plot Summary for "The Untouchables" Stranglehold (1961)from the internet movie database

Frank Makouris, associated with the New York mob and Dutch Schultz, controls the city's Fulton Fish Market which provides much of the fish in the Eastern United States. Anything the fisherman might need - docking rights, ice, wholesalers - can only be had with a payment to Makouris. Eliot Ness is invited by the US Attorney in New York to help bring Makouris down. They find that one fisherman in particular, Capt. Joe McGonigle, is prepared to help them out but even then, Makouris manages to have Ness' phone tapped and they get to McGonigle before he can testify. Ordered by the mob bosses to knock off the violence, Makouris oversteps the mark and the Syndicate orders him to get rid of his enforcer, Lennie Shore.Ricardo Montalban as a Greek!

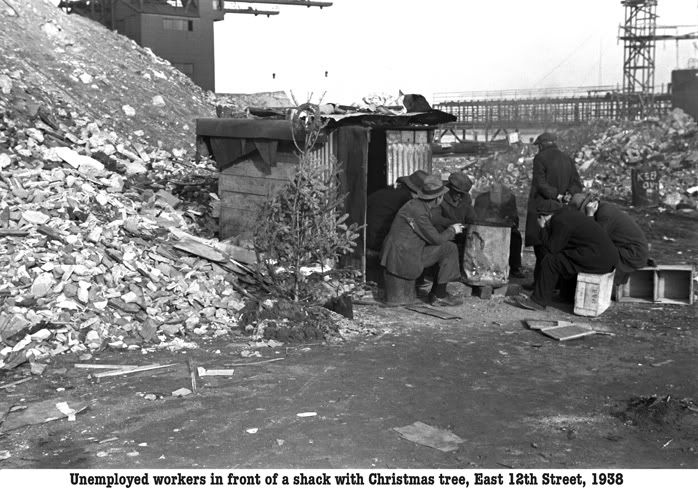

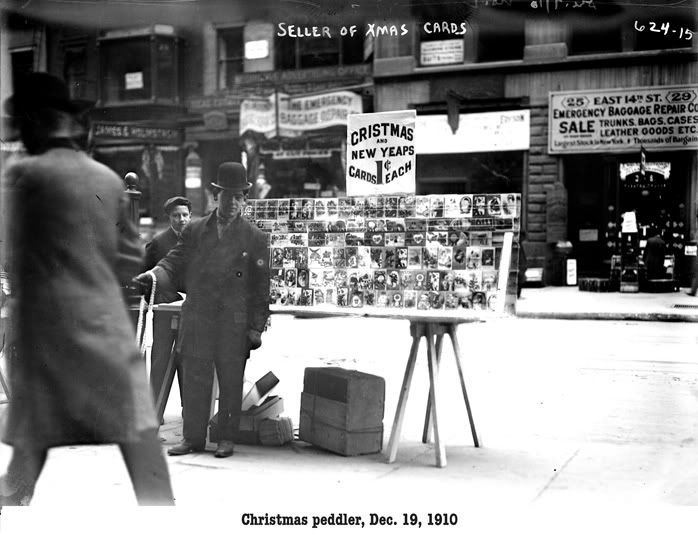

A KV Christmas Present: Archival Images From The Museum Of The City Of New York

kv-mcny

The Museum has recently added thousands of images to its digital collection.

I found these KV gems there. The nytimes had an article about the new feature on December 23

The first four appear to be from the west court. The fifth picture I believe is Cherry Street looking west from Market. The last picture I believe is from the east court looking towards Cherry Street.

The Museum has recently added thousands of images to its digital collection.

I found these KV gems there. The nytimes had an article about the new feature on December 23

The first four appear to be from the west court. The fifth picture I believe is Cherry Street looking west from Market. The last picture I believe is from the east court looking towards Cherry Street.

Thursday, December 23, 2010

1953: "Old Timers" Remember The Triangle Fire: Jacob Panken

about Jacob Panken

Jacob Panken (1879 – 1968) was an American socialist politician, best remembered for his tenure as a New York municipal judge and frequent candidacies for high elected office on the ticket of the Socialist Party of America.

He was born January 13, 1879, in Kiev, Ukraine, then part of the Russian empire. He was the son of ethnic Jewish parents, Herman Panken and Feiga Berman Panken. His father was employed as a merchant.The family emigrated to the United States in 1890, arriving at New York City, a city in which the family settled.

Panken went to work at age 12, working first making purses and pocketbooks. He later worked as a farmhand, a bookkeeper, and an accountant.

Panken married the former Rachel Pallay on February 20, 1910. His wife would eventually be a Socialist Party politician in her own right, running for the New York City Board of Aldermen in 1919 and for New York State Assembly in 1928 and 1934.

In 1901, Panken left accountancy to go to work as an organizer for the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union. Returning to the industry in which he first worked as a child, Panken was an organizer of the Purse and Bag Workers' Union in 1903.

Panken graduated from New York University Law School in 1905 and became a practicing attorney in the city.

An outspoken opponent of World War I, Panken was a member of the People's Council for Democracy and Peace in 1917.

Panken attended the 1912 National Convention of the Socialist Party of America (SPA), to which he delivered the report of the "Jewish Socialist Agitation Bureau," forerunner of the Jewish Socialist Federation.

Panken was a public advocate of civil rights for black Americans, sitting on the advisory board of an organization established in 1919 by Chandler Owen and A. Phillip Randolph, the National Association for the Promotion of Labor Unionism Among Negroes, the motto of which was "black and white workers unite."

Panken was a leading figure in the bitter 1919 Emergency National Convention of the SPA, chairing the all-important Credentials Committee which acted as a filter to insure the victory of the "Regular" faction headed by Executive Secretary Adolph Germer, New York state party leader Julius Gerber, and National Executive Committee member James Oneal. He was also a delegate to subsequent SPA conventions held in 1920, 1924, and 1932.

Panken was frequent candidate for public office on the ticket of the Socialist Party. He was first a candidate for New York State Senate in the 11th District in 1908.[ He ran for State Assembly from New York County's 8th District the following year. In 1910 he ran for Justice of the New York Supreme Court for the first time, later pursuing the office again in 1929 and 1931.

Panken won election to a ten-year term as a municipal judge in New York in 1917, the first Socialist to be elected to New York City's Municipal Court. In 1927, he declined to accept endorsement from both the Republican and Communist parties and was defeated in his re-election bid. The 1927 election was the first in the New York City boroughs of Manhattan and Brooklyn to use voting machines in all districts. The result of the election was challenged, with allegations of vote rigging, including an allegation that the lever for Panken's name was rendered inoperable in one district.

While sitting as a judge, he remained a candidate for high offices on behalf of the Socialist Party, pursuing a seat as U.S. Senator from New York in 1920 and running for Mayor of New York in 1921. He was ran for U.S. Congress in 1922 and 1930; for Governor of New York in 1926, and for Chief Judge in 1932.

During the bitter internal party fight that swept the Socialist Party during the second half of the 1930s, Panken was a committed adherent of the so-called "Old Guard faction" headed by Louis Waldman and James Oneal. In 1936 he exited the SPA along with his co-thinkers to help found the Social Democratic Federation.

Panken was one of the most outspoken anti-Zionists on the Jewish left, a key supporter of the Jewish Newsletter published by William Zukerman as well as of the American Council for Judaism.

In 1934, he was appointed to the Domestic Relations Court by Mayor Fiorello La Guardia and served until his retirement in 1955.

Panken died in The Bronx on February 4, 1968, at the age of 89. His papers are housed at the Wisconsin Historical Society on the campus of the University of Wisconsin in Madison.

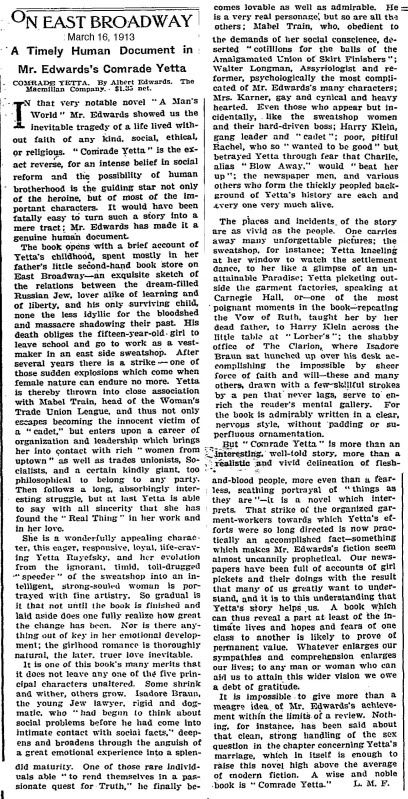

Comrade Yetta Of East Broadway

link to download the book

A review of a 1913 book that dealt with striking garment workers.

an excerpt

Source: The Cry For Justice: An Anthology of the Literature of Social Protest, ed. by Upton Sinclair, John C. Winston Co., 1915.

Transcribed: for marxists.org in January, 2002.

A review of a 1913 book that dealt with striking garment workers.

an excerpt

Source: The Cry For Justice: An Anthology of the Literature of Social Protest, ed. by Upton Sinclair, John C. Winston Co., 1915.

Transcribed: for marxists.org in January, 2002.

(The story of an East Side sweat-shop worker who becomes a strike-leader. The present scene describes a meeting in Carnegie Hall)

YETTA stood there alone, the blood mounting to her cheeks, looking more and more like an orchid, and waited for the storm to pass.

"I'm not going to talk about this strike," she said when she could make herself heard. "It's over. I want to tell you about the next one--and the next. I wish very much I could make you understand about the strikes that are coming....

"Perhaps there's some of you never thought much about strikes till now. There's been strikes all the time. I don't believe there's ever been a year when there wasn't dozens here in New York. When we began, the skirt-finishers was out. They lost their strike. They went hungry just the way we did, but nobody helped them. And they're worse now than ever. There ain't no difference between one strike and another. Perhaps they are striking for more pay or recognition or closed shops. But the next strike'll be just like ours. It'll be people fighting so they won't be so much slaves like they was before.

"The Chairmen said perhaps I'd tell you about my experience. There ain't nothing to tell except everybody has been awful kind to me. It's fine to have people so kind to me. But I'd rather if they'd try to understand what this strike business means to all of us workers--this strike we've won and the ones that are coming....

Tuesday, December 21, 2010

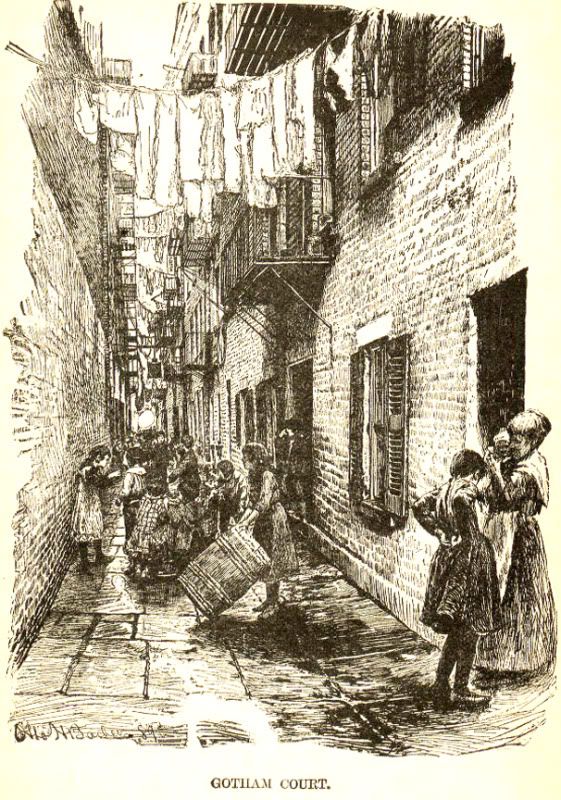

Gotham Court, Sweeney's Shambles and Paradise Alley

Knickerbocker Village's favorite NYC historian Kevin Baker will be speaking before Bronx teachers next month as part of a Teaching American History Grant. The topic will be his book Paradise Alley. Here, in an excerpt from the full interview, Kevin discusses the history surrounding the book

A Conversation with Kevin Baker

Q. You've written Dreamland, a novel set in 1910s New York, and you've done research for Harold Evan's The American Century. How did you come across the historical events described in Paradise Alley and why did you decide to write about them?

KB: I first came across the events depicted in Paradise Alley, when my father gave me a copy of Herbert Asbury's The Gangs of New York to read, over 30 years ago. Having grown up in America in the 1960s, I was not terribly surprised by the idea of urban riots, or by protests over a draft — it seemed, in those days, that every time you turned on the TV you saw a halftrack rolling down a city street — but I was stunned by how violent and furious these protests from the 1860s were. Asbury's book, which is now emerging as a classic of our hidden history, is not terribly long on accuracy; an estimated 119 people died, instead of the 2,000 he claims. But it was, still, the worst riot in American history, and something that was very alien to the received history I had about the Civil War, and what kind of a fight it was, and who the good guys and the bad guys were. I wanted to know more — and what I learned, I thought, made for a great story.

Q. You've placed three women at the center of your narrative and each is portrayed with a striking degree of intimacy. How did you, as a man, get to know these characters? Was it difficult finding their voices?

KB: I always find it difficult to get any character's voice down. I know that the conventional wisdom of today is that one should not be able to truly depict anyone not exactly one's own self, but that would mean the death of literature. There is always a lot of groping in the dark, and it's even harder, of course, when you're dealing with a different time period. I have been fortunate enough to know many wonderful women in my life, my wife, sisters, mother, many friends. I have learned a great deal from them all, and I feel that I know many of them better than the male friends and relatives I have. The gap between the sexes is great, but it is not so wide as to preclude the basics of human love, fear, desire, greed, etc.

Q. In Paradise Alley, you're delving deep into the heart of Irish Roman-Catholicism. Was it easy to become familiar with the cultural norms and behavioral patterns of a different religion?

KB: As it happens, much of my father's family is Catholic, and I have attended a number of masses in my life. It's not exactly another world to me. But yes, I was brought up in different Protestant faiths — and on top of this difference, I had to find out what the Catholic church in America was like in the 19th century. In this endeavor, I was fortunate enough to have the help of several priests in the New York area, all of whom had a good historical perspective, and several books that I cite in the bibliography. The differences between then and now are not vast, but in general the Catholic church in America was, at the time of Paradise Alley, poorer, more defensive, more besieged, more persecuted, somewhat more proper and conservative, and perhaps a little more directly involved with life in the streets, where most of its communicants were living.

Q. Your use of geographical landmarks brings to life vividly the anatomy of historical New York. Which places are real and which are fictional? Where could we find Paradise Alley today?

KB: Paradise Alley was a very real place, an alley that emerged from a terrible double tenement known as "Sweeney's Shambles." Both are long gone, thank goodness. Their approximate location was just off Cherry Street, behind where the New York Post printing plant is today, and about where the Smith Houses currently stand. The anatomy of the whole Fourth Ward over there is very much changed now, and scarcely recognizable. Gone, too, are the old homes of The New York Times and the Tribune, the grand old hotels such as the Astor House and the St. Nicholas, and most of the tenements of the old Five Points.

But many other buildings are still standing, such as the churchyard of the Old St. Patrick's (the church itself burned and was rebuilt shortly after the Civil War), where Tom meets Deirdre; New York's graceful, Georgian City Hall; Federal Hall, the old Sub-Treasury building, where they kept the gold, and quite a few older residential buildings. The oldest known tenement, for instance — dating back to at least 1824 — still stands, at 65 Mott Street, in the heart of Chinatown. The Lower East Side of New York is truly a unique place in America, a neighborhood that has been a poor, immigrant community continuously for at least 175 years. The ethnic groups have changed — from Irish and German, to Jewish, Eastern European, and Italian, to Hispanic and Asian — but the flavor of struggle, of aspiration, of sheer density and poverty, still remains. To get a very vivid idea of how new Americans lived from the 1850s to the 1930s, I would highly recommend that one visit The Lower East Side Tenement Museum, at 97 Orchard Street, which has preserved an old tenement and created inside replicas of how various apartments looked during different ages. I certainly did — which is why no location in Paradise Alley is made up out of wholecloth.

Down Among The Lowly: 1871 In The Fourth Ward

4th-ward-1871

the last page of the doument mention Sweeney's Shambles

an excerpt from rootsweb

the last page of the doument mention Sweeney's Shambles

an excerpt from rootsweb

One of the main streets in the Fourth Ward was Water Street. The police reported that every building along Water housed either a saloon, dance hall or bordello on one of its floors. It was common for a family to live one floor away from a bordello. For almost a quarter of a century, Water Street was the highest crime area in New York City.

Cherry Street became infamous during the mid-1800s. Cherry was lined with boarding houses that were known as 'crimp houses.' Since the Fourth Ward was on the water, many ships would dock and its crew disembark into the city for the night. Many seamen would rent rooms in these boarding houses for the night. However, though the sign outside said 'boarding house' it was just a ruse. The unsuspecting seaman would pay for his room and retire for the night. Once the seaman was asleep, the denizens of the boarding house would sneak into his room, usually through a hidden panel in the wall, then 'crimp' or rob and murder him. The seaman's body was then dragged downstairs and dumped into the sewer. 'Crimp house' residents usually consist of the

landlord, prostitutes and maybe a bartender or two. Sometimes the people of the boarding house would simply drug the seaman while he enjoyed some liquor on the ground floor of the building. Chloral hydrate was the drug of choice for crimpers, but laudanum and opium were also used.

These drugs could be purchased fairly easily on any street in the Fourth Ward. Opium was not hard to come by as the area was full of opium dens. The crimpers would put such a large dosage of chloral hydrate into the seaman's drink, that it would kill him shortly after consuming it. Crimp houses had a mortality rate of seventeen percent. Many women found work as prostitutes in the numerous bordellos throughout the Fourth Ward. Children were also sold into prostitution -- their customers

being either adults or other children. Unlike Five Points which was largely a business area, the Old Fourth Ward was mostly residential. Tenements littered every block. Arch Block was a famous tenement building that was so large it covered the entire block from Thompson to Sullivan Street between Broome and Grand. While the Old Brewery in Five Points was enough to give people nightmares, it wasn't as bad as Gotham Court, nicknamed Sweeney's Shambles. Sweeney's Shambles held the dishonor of being the worse tenement in New York City history. Not much is known now of the history of the building except that the nickname came from the landlord, Sweeney.

Sweeney's Shambles was a huge imposing tenement complex that stood at 36 and 38 Cherry Street. It consisted of two rows of connected tenement houses, 130 feet in length. It was the home of over 1000 people, mostly Irish. You could only enter Sweeney's Shambles through one of two alleyways that ran around the building. On the East side was Single Alley, a mere 6 feet in width. On the West side was the 9-foot wide Double Alley, also known as Paradise Alley.

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire Graphic History Book

A good representation of the story for younger kids and struggling readers. An excerpt I put together from its google books' site

Triangle Comic Combined

Triangle Comic Combined

Monday, December 20, 2010

Hyman Meshel, Triangle Shirtwaist Fire Survivor

While armed troops gather in Minsk today due to a standoff in recent elections one can recall a son of Minsk who survived a much more harrowing event almost 100 years ago.

Meshel Docs

I put together the Times' story of his survival along with census records of Meshel to chart his life after the fire. Sometime after 1920 he moved from his East 15th Street address to Plainfield, New Jersey and became a baker. He was married to a woman named Fanny. He lived at 525 Somerset Street. Sometime around 1940 he moved to Newark. The Social Security Death index has him passing away in January of 1969 in Cape Canaveral Florida at the age of 80.

Meshel Docs

I put together the Times' story of his survival along with census records of Meshel to chart his life after the fire. Sometime after 1920 he moved from his East 15th Street address to Plainfield, New Jersey and became a baker. He was married to a woman named Fanny. He lived at 525 Somerset Street. Sometime around 1940 he moved to Newark. The Social Security Death index has him passing away in January of 1969 in Cape Canaveral Florida at the age of 80.

Brooklyn Fancy Cakes......4th Ward Origins

An excerpt from the 12/17 nytimes

Brooklyn’s Allure? Fancy Cakes, Dahling

By HELENE STAPINSKI

Because of cheap rents and relative proximity to the affluent if demanding customers of Manhattan, at least five bakeries have settled within a two-mile radius of one another. “You’re not going to get customers to come out and meet you in Queens,” Ms. Gamble said. “But they will come in to Brooklyn.”.....

A few blocks up Columbia Street from Elegantly Iced is Nine Cakes, which Betsy Thorleifson, a former harpsichordist from Washington State, opened just over a year ago, focusing on tiered specialty cakes. In Carroll Gardens, Karyn Kwok opened Kakes in May, and this summer displayed her cartoonish cakes, including giant cheeseburgers and Oreos, in her Sackett Street window. Two miles away, in a second-floor kitchen, is Made in Heaven, which moved from Staten Island to Gowanus two years ago in search of a “higher-end clientele,” Lisa Zagami said. She runs the business with her husband and 21-year-old daughter.

The Zagamis trace their baking roots to Lisa’s father, Anthony, who ran Savola, an Italian bakery on the Lower East Side, for 35 years. Lisa’s husband, Victor, worked at Brooklyn’s best Italian bakeries — like Villabate and Argento’s — before becoming a correction officer for 20 years. After he retired, “we dragged him back in,” Lisa Zagami said.

Their daughter, Victoria, graduated recently from the Culinary Institute of America in Hyde Park and worked in Manhattan with Colette Peters — whom Lisa Zagami calls “the Picasso of cakes” — before joining her parents’ 15-year-old wedding cake operation.

Victoria Zagami’s first edible artwork was helping her mother design her first communion cake at age 7. Until she joined the family business a year ago, the shop did mostly traditional tiered wedding and special-occasion cakes. “Now we’re doing more intricate, whimsical things,” she said....

Brooklyn’s Allure? Fancy Cakes, Dahling

By HELENE STAPINSKI

Because of cheap rents and relative proximity to the affluent if demanding customers of Manhattan, at least five bakeries have settled within a two-mile radius of one another. “You’re not going to get customers to come out and meet you in Queens,” Ms. Gamble said. “But they will come in to Brooklyn.”.....

A few blocks up Columbia Street from Elegantly Iced is Nine Cakes, which Betsy Thorleifson, a former harpsichordist from Washington State, opened just over a year ago, focusing on tiered specialty cakes. In Carroll Gardens, Karyn Kwok opened Kakes in May, and this summer displayed her cartoonish cakes, including giant cheeseburgers and Oreos, in her Sackett Street window. Two miles away, in a second-floor kitchen, is Made in Heaven, which moved from Staten Island to Gowanus two years ago in search of a “higher-end clientele,” Lisa Zagami said. She runs the business with her husband and 21-year-old daughter.

The Zagamis trace their baking roots to Lisa’s father, Anthony, who ran Savola, an Italian bakery on the Lower East Side, for 35 years. Lisa’s husband, Victor, worked at Brooklyn’s best Italian bakeries — like Villabate and Argento’s — before becoming a correction officer for 20 years. After he retired, “we dragged him back in,” Lisa Zagami said.

Their daughter, Victoria, graduated recently from the Culinary Institute of America in Hyde Park and worked in Manhattan with Colette Peters — whom Lisa Zagami calls “the Picasso of cakes” — before joining her parents’ 15-year-old wedding cake operation.

Victoria Zagami’s first edible artwork was helping her mother design her first communion cake at age 7. Until she joined the family business a year ago, the shop did mostly traditional tiered wedding and special-occasion cakes. “Now we’re doing more intricate, whimsical things,” she said....