Bernard E. Lemonick was an All-America football player at the University of Pennsylvania from 1948-1950. He was my mother's first cousin. I never met him, he's still alive and well. It's a long sad story of family estrangement. As a kid I was fascinated to learn about this famous cousin from my mother. His brother Aaron, a physics professor at Princeton had greater accomplishments, but to think a Jewish All American!

Bernie's Career Highlights: "An outstanding guard at Pennsylvania, Lemonick was considered one of the nation's best lineman during his career. In 1949, Bernie was named AP All-Ivy League second team. In 1950, he was Helms Athletic Foundation All-America defensive team, UP All-America second team, and Grantland Rice All-America honorable mention. Lemonick played in the 1951 East-West Shrine game, the Hula Bowl, and on the College All-Star team against the Cleveland Browns. During his senior season, Bernie was also a two-time selection as National Lineman of the Week.

After graduating with honors in 1951 (he was the 1951 class president as well), Lemonick became a line coach at St. Joseph's Prep and then returned to Penn in 1955 as an assistant football coach. In 1959, his last season as a coach at Penn, Bernie was the defensive line coach for the school's first Ivy League Championship team. In 1985, he received the Distinguished American Award from the National Football Foundation and College Hall of Fame. Lemonick recently received the 1996 University of Pennsylvania Alumni Award of Merit and was inducted into the state of Pennsylvania's 1995 Sports Hall of Fame City All-Star chapter. He is also a member of the Philadelphia Jewish Sports Hall of Fame and the Penn Athletic Hall of Fame."

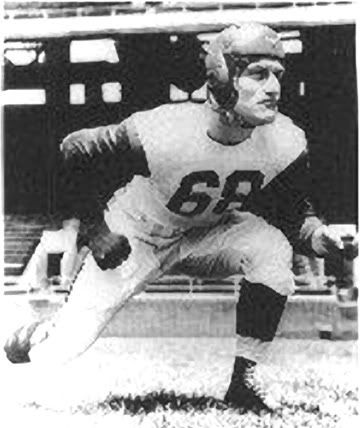

The above photo comes from this 2003 article

Hurrah For …What Was That Again?

The Quaker spirit lives on, in Franklin Field’s upper tiers and the occasional freshman heart.

By Patrick Brugh | I hop down the last set of steps into the basement of Houston Hall the night before Penn stomps Duquesne into the ground in the football season opener on September 20. A small herd of freshmen mill around the Hall of Flags and pick red and blue pom-poms from a box near the door. The room echoes with each horn-snort from the marching band and titters with the shouts of Penn cheerleaders as they skip and twirl like red-and-blue whirligigs.

This is “Football 101,” the would-be grand kickoff to the Penn football season. But the weather has dampened its grandeur a bit. “It seems that this is about the only thing around here [Hurricane Isabel] did wash out,” says Katherine Lowe, dean of Ware College House, which is sponsoring the event. The advertised “old-fashioned pep rally” was “supposed to be in the Quad,” she says as a few more freshmen scuffle past the pom-pom box to seats in the back of the room, “but because of Isabel, we had to move it indoors.” I can envision a bunch of first-years, unaware of the change, hanging out in lower Quad wondering where the hell the band was.

Music piping full blast from the band and more bopping cheerleaders signals the rally’s start. Two little boys in the middle of the room hop onto chairs and flick their pom-poms to the drum beats. Eight students walk up to the second row and sit down by themselves after checking to see if anyone they know is around. The rest of the crowd sits quietly in their seats behind me.

The band master introduces himself, and then head football coach Al Bagnoli assures us that there is going to be enough passing for a four-hour game. He reads the names of the team captains, and a sudden roar from the back startles me. Most of the football team has been hiding with the freshmen behind me, and they are whooping and catcalling at the three massive senior captains.

The promotion for the event had promised a football grad who would talk about the “good old days,” and Bagnoli presents Bernie Lemonick C’51, who certainly fits the bill. Lemonick displays his uniform from his days as a lineman. The red-and-blue armstripes and the giant 68 emblazoned on the white field of the chest must have inspired fear in the hearts of the Quakers’ opponents the year Bernie earned All-American status. He brings back an era of students crowding the stands and Franklin Field bursting with the cries of 50,000 fans, when Penn would play teams like Ohio State, Notre Dame, and Pittsburgh. Cataloguing Penn’s tradition of football greatness, he appeals to the 30 or 40 Quaker faithful in the room: “All the people that you know in the dorms: get them to come out to the games. That’s where they belong on Saturday, because this team deserves all the attention you can give them.”

Bernie reads a quote from the Duquesne quarterback—“It’s probably the biggest game of our careers. It’s Penn, and it’s Penn’s opener, and there will be a great crowd.”—and makes a prediction: “There’s only one thing he’s right on. There’s going to be a great crowd, and they’re going to get their asses handed to them!” The students holler and clap so loud it seems to shake the flags of the other Ivies that hang from the walls above us. The two little boys hop on their chairs and flick their pom-poms wildly as the band begins to play.

The band master regains the podium and explains traditions like jingling keys, throwing toast, and singing “The Red and the Blue.” When the song starts, I realize I am the only one in the back who leaps up to sing. Slowly a few more join me, starting with the football team and then the other students, most of whom have never heard this song in their lives, and certainly don’t know the words. I belt out the lyrics in my wretched voice, and a brunette down the row looks at me like I have a third arm. Just wait till tomorrow, I think, when the band plays at the end of the game, and thousands of students cock their arms in pride.

I get to Bernie Lemonick after the world finishes greeting him, and the mass exodus of freshmen has crammed out the single door like an impromptu fire drill. When I ask if I can speak with him, he crinkles his sparkling young eyes behind his glasses and nods. We go outside for some air, and sit awkwardly on a stone wall behind Houston.

“You knew when you first came in that there were certain things that they expected in terms of behavior, activity, and response to things like football and basketball games,” he says of his student days. “I expect that at a gathering like this, they would have had most of the freshmen class. There should have been 2,000 people in there.”

He tells me that the low attendance at games upsets him a little, “because I think it reflects the kind of thinking that goes on, that this is kind of an appendage, that it doesn’t mean a hell of a lot.”

When I ask how the University could change that, he tells me, “If, for example, Penn had a schedule that included an Army and a Navy, a mix of opponents, people would want to come out and see them and every one of these kids would be out there.” He sweeps his arm behind him toward the Quad and looks me straight in the eyes. “That’s not the way it works today in the Ivy League. They want to maintain a certain academic image that does not necessarily include football or athletics.

“If you have a schedule, where athletes could come here and show off what they can do, so they can go to the next step, I think you would draw different players,” he adds. “Now the thing is, you can’t just have an imbecile come to the University, because we won’t take anyone just because they’re a football player.”

He is proud that he comes to every game, and when I ask him about the enthusiasm of the students who do show up, he says with a smile, “They’re pretty creative, those kids.”

I’m five minutes late for the game as I haul down Spruce. The guards check my bag and my Penn Card at the student entrance, and I bound up the steps and down to the section where my swim team sits. On the way, I walk up through the sparsely populated alumni section. Arching from right to left over the almost empty Franklin Field chairbacks are nearly 8,000 Penn students and supporters. The other side of the stadium boasts a smattering of Holy Ghost fans.

I meet up with the rest of my team on the top tier. They are tossing little chunks of bread at each other and rising to join the occasional communal scream. The upper deck is packed between the 20-yard lines, mostly with other athletes trying to get to know their recruits for the weekend. In the third quarter, when Penn is up 30 to 10, the swimmers and most of the top section decide to get cheesesteaks. Suddenly I’m sitting alone with the kicker’s girlfriend and a fat guy reclined against the railing eating potato chips off his stomach.

I decide to check out the student section after the toast is thrown at the end of the third quarter, but the score is 51-10 by then, and from above, the lines of departing students look like ants fleeing a stream of water. “Why is everyone leaving?” a freshmen downstairs asks me as I slide next to him. “I’m coming to every home game, and I’m not leaving until the last second ticks away.”

I don’t have an answer, except that no one wants to watch a blowout, and I consider what Bernie said the night before about the football schedule.

The student section, despite bleeding numbers, is still fomenting. It gathers steam from the rabid football fans that remain. Bored by the lack of competition on the field, the crowd heckles the band until they play more songs.

When the game ends, after a mere two hours and 45 minutes, I am surprised not to see the limbs and helmets of Dusquesne players jutting from the field. The game was scoreless in the fourth quarter, and the visitors’ side of the field is deserted, but as always, win or lose, while the players roll across the field to shake hands, the band pours out “The Red and the Blue,” and the Quakers cock their arms with the pride of Pennsylvanians.

No comments:

Post a Comment