from the nytimes city section of 5/4/08, an excerpt follows

A Strange City Called Home, By DAVE ITZKOFF

IN the opening moments of Grand Theft Auto IV, the latest chapter of the cinematically styled video game franchise, two men are standing at the side of a boat, watching a familiar sight drift into view. Through their eyes, we see a digitized, 21st-century retelling of a scene that greeted numerous generations of new arrivals to an unknown country: the eastern end of a long, narrow island, with a towering metal spire emerging from its belly, and a diminutive green statue beckoning from a tiny point off the island’s southern tip.

We think we know what we are seeing, until one of the game’s characters identifies the land mass for us.

“Liberty City,” he says to his shipmate in a vaguely East European accent. “You ever been?”

And before I even sat down to play the game, I could honestly say that I had.

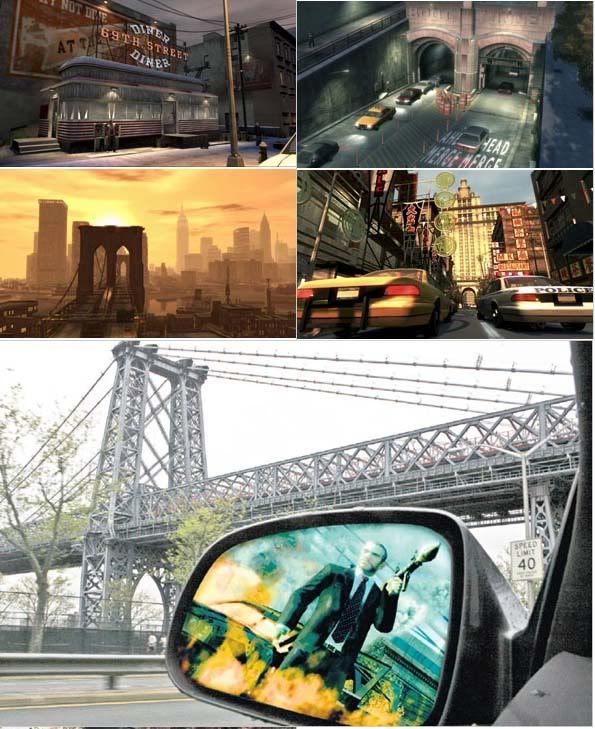

Liberty City, the pixilated playground where the action of Grand Theft Auto IV occurs, is New York City, and it is not. Like previous installments of the game, which has sold more than 70 million copies in the last decade — abbreviated G.T.A., in the same sanitized way that Kentucky Fried Chicken became KFC — this newest edition (released on Tuesday for the Xbox 360 and PlayStation 3 systems) sets players loose in an environment closely modeled on a real American metropolis, usually at some notorious time in its history.

The environs of Grand Theft Auto: Vice City, released in 2002, were inspired by 1980s-era Miami, the pastel-hued setting for crime dramas like “Scarface” and “Miami Vice.” For a 2004 sequel, Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas, the game relocated to three interconnected cities based on Los Angeles, San Francisco and Las Vegas, against a 1990s backdrop of gangsta rap and gang violence.

While moving its story forward to the present day, G.T.A. IV largely restricts itself to a single city — one at the height of its prosperity and during an ebb in crime. The game makes no attempt to disguise the fact that it is designed to look, sound and feel like the city I have lived in for nearly all 32 years of my life.

As many others have already noted, Liberty City is a dead ringer for New York: It’s divided into boroughs with distinct populations and architectural styles; it has most of the same suspension bridges and historic landmarks in the places you’d expect to find them; and its streets are always teeming with traffic and unruly pedestrians.

This game is hardly the first to try to replicate some portion of the New York experience — programmers have been trying to do this for decades. But Grand Theft Auto IV is the most contemporary attempt at this experiment, and may be the most realistic made available to a mass audience.

It’s also a game that has an extra layer of resonance for indigenous New Yorkers. With all the knowledge, confidence, predispositions and prejudices we possess, we’re not only better equipped to detect the many references and insider jokes, we may even come out of the game thinking differently about the real-life New York we’ve always known.

For a native New Yorker, the game is both comfortingly routine and eerily disorienting; you find yourself playing because it is a limitless escape and a consequence-free confinement. Liberty City is like nowhere I’ve ever visited, even as it tries with all its heart and soul to remind me of a place with which I’m already intimately acquainted.

No comments:

Post a Comment