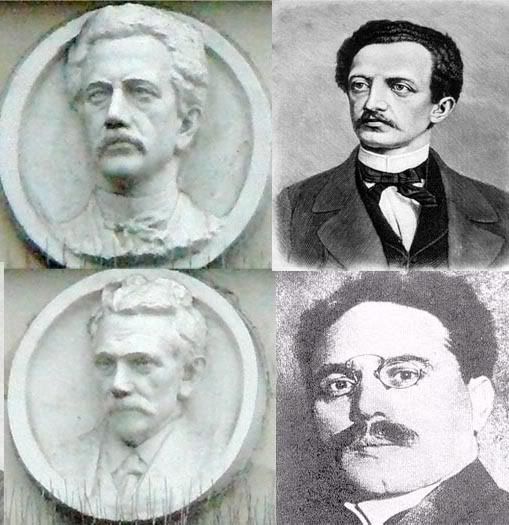

On The Top:

Ferdinand Lassalle (11 April 1825 — 31 August 1864) was a German jurist and socialist political activist.

Lassalle came from a prosperous Jewish family in Loslau later Breslau, Prussia; his father was a silk-merchant and intended his son for a business career, sending him to the commercial school at Leipzig. Lassalle himself, however, had other plans and got himself transferred to university, first in Breslau and afterwards in Berlin. His favourite studies were philology and philosophy; he became a close follower of Hegel. Having completed his university studies in 1845, he began to write a work on Heraclitus from the Hegelian point of view; but it was soon interrupted and was not published until 1858.

It was in Berlin, towards the end of 1845, that he met Countess Sophie von Hatzfeldt. She had been separated from her husband for many years, and had problems with him on questions of property and the custody of their children. Lassalle attached himself to the countess's cause, made special study of law, and, after bringing the case before thirty-six tribunals, reduced the count to a compromise on terms favourable to his client.

The court case, which lasted ten years, gave rise to some scandal, especially that of the Cassettengeschichte (Casket Affair), which pursued Lassalle all the rest of his life. This arose out of an attempt by the countess's friends to get possession of a bond for a large life annuity settled by the count on his mistress, Baroness von Meyendorff, to the disadvantage of the countess and her children. Two of Lassalle's comrades succeeded in carrying off the casket, which contained jewels, from the baroness's room at a hotel in Cologne. They were prosecuted for theft, one of them being condemned to six months imprisonment. Lassalle, accused of moral complicity, was acquitted on appeal.

Lassalle took part in the revolutions of 1848-49; as a result he underwent a year's imprisonment in 1849 for resistance to the authorities of Düsseldorf and was banned from living in Berlin. Until 1859 Lassalle resided mostly in the Rhineland, dealing with the suit of the countess, and finishing the work on Heraclitus. In this time he was not much involved in political agitation, but remained interested in the labour movement.

In 1859 Lassalle returned to Berlin, entering the city disguised as a carter, and, through the influence of Alexander von Humboldt with the king, received permission to stay there. The same year he published a pamphlet on the war in Italy and how Prussia should act: he warned Prussia against going to the rescue of Austria in her war with France. He pointed out that if France drove Austria out of Italy it would be able to annex Savoy, but would not be strong enough to prevent Italian unification under King Victor Emmanuel. Prussia, he said, should form an alliance with France to drive out Austria and also to gain power in Germany. In 1861 Lassalle published System der erworbenen Rechte (System of Acquired Rights) on this subject.

In early 1862, the struggle had begun between Otto von Bismarck and the liberals in Prussia. Lassalle believed that the liberal politician Hermann Schulze-Delitzsch's co-operative schemes on the principle of self-help were utterly inadequate to improve the condition of the working classes. Lassalle himself had a fashionable, extravagant lifestyle, but now he threw himself into a new career as a political agitator, travelling around Germany, giving speeches and writing pamphlets, in an attempt to organise and rouse the working class.

Although Lassalle was a member of the Communist League, his politics were strongly opposed by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Marx and Engels thought that Lassalle was not a true Communist as he directly influenced Bismarck's government (in secret albeit) on the issue of universal suffrage, among others. Élie Halévy would later write on this situation:

Lassalle was the first man in Germany, the first in Europe, who succeeded in organising a party of socialist action. Nevertheless, if he had not unfortunately been born a Jew, Lassalle could also be hailed as a forerunner in the vast halls where National Socialism is acclaimed to-day...When in 1866 Bismarck founded the Confederation of Northern Germany on a basis of universal suffrage, he was acting on advice which came directly from Lassalle. And I am convinced that after 1878, when he began to practise "State Socialism" and "Christian Socialism" and "Monarchial Socialism," he had not forgotten what he had learnt from the socialist leader. ”

As a result, when Lassalle founded the Allgemeiner Deutscher Arbeiterverein (General German Workers' Association, ADAV) on 23 May 1863, Marx's supporters in Germany did not join it. Lassalle was the first president of the ADAV, which was the first German labour party, from 23 May 1863 to 31 August 1864. This party later became the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD).

The SDP was formed in 1875, when the ADAV merged with the SDAP (Social Democratic Workers' Party of Germany), to a great extent due to Lassalle's efforts. Lassalle wanted to participate in German politics. Wilhelm Liebknecht and August Bebel, who were Marxists and opposed reformist politics, also joined the party. From its founding, the Social Democratic Party was divided between those who advocated reform and those who advocated revolution.

In Berlin, Lassalle had met a young woman, Hélène von Dönniges, and in the summer of 1864 they decided to marry. She, however, was the daughter of a Bavarian diplomat then resident at Geneva, who would have nothing to do with Lassalle. Hélène was imprisoned in her own room, and soon, apparently under pressure, renounced Lassalle in favour of another admirer, Count von Racowitza. Lassalle sent a challenge both to the lady's father and to Racowitz, which was accepted by the latter. At the Carouge, a suburb of Geneva, a duel took place on the morning of 28 August 1864. Lassalle was mortally wounded, and he died on August 31. The final events of his life were described in George Meredith's novel The Tragic Comedians (1880). He is buried in Breslau (now Wrocław), in the old Jewish cemetery.

On the bottom:

Karl Liebknecht (13 August 1871 - 15 January 1919) was a German socialist and a co-founder of the Spartacist League and the Communist Party of Germany.

Born in Leipzig, Karl Liebknecht was the son of Wilhelm Liebknecht, one of the founders of the Social Democratic Party of Germany. However, Karl Liebknecht was more radical than his father; he became an exponent of Marxist ideas during his study of law and political economy in Leipzig and Berlin. After serving with the Imperial Pioneer Guards in Potsdam from 1893 to 1894 and internships in Arnsberg and Paderborn from 1894 to 1898, he earned his doctorate at Würzburg in 1897 and moved to Berlin in 1899 where he opened a lawyer's office with his brother, Theodor Liebknecht. Liebknecht married Julia Paradies on 8 May 1900; the couple had two sons and a daughter before Liebknecht's wife died in 1911.

As a lawyer, Liebknecht often defended other left-wing socialists who were tried for offences such as smuggling socialist propaganda into Russia, a task in which he was involved himself as well. He became a member of the SPD in 1900 and was president of the Socialist Youth International from 1907 to 1910; Liebknecht also wrote extensively against militarism, and one of his papers, "Militarismus und Antimilitarismus" ("militarism and antimilitarism") led to his being arrested in 1907 and imprisoned for eighteen months in Glatz, Prussian Silesia. In the next year he was elected to the Prussian parliament, despite still being in prison.

Liebknecht was an active member of the Second International and a founder of the "Socialist Youth International". In 1912 Liebknecht was elected to the Reichstag as a Social-Democrat, a member of the SPD's left wing. He opposed Germany's participation in World War I, but following the party line he voted to authorise the necessary war loans on 4 August 1914. On 2 December 1914 he was the only member of the Reichstag to vote against the war, the supporters of which included 110 of his own Party members. He continued to be a major critic of the Social-Democratic leadership under Karl Kautsky and its decision to acquiesce in going to war. In October that year, he also married his second wife, art historian Sophie Ryss.

At the end of 1914, Liebknecht, together with Rosa Luxemburg, Leo Jogiches, Paul Levi, Ernest Meyer, Franz Mehring and Clara Zetkin formed the so-called Spartacist League (Spartakusbund); the league publicized its views in a newspaper titled Spartakusbriefe ("Spartacus Letters") which was soon declared illegal. Liebknecht was arrested and sent to the eastern front during World War I for the group's echoing of Russian Bolsheviks' arguments for a Proletarian Revolution; refusing to fight, he served burying the dead, and due to his rapidly deteriorating health was allowed to return to Germany in October 1915.

Liebknecht was arrested again following a demonstration against the war in Berlin on 1 May 1916 that was organized by the Spartacus League, and sentenced to two and a half years in jail for high treason, which was later increased to four years and one month.

Liebknecht was released again in October 1918, when Max von Baden granted an amnesty to all political prisoners. Following the outbreak of the German Revolution, Liebknecht carried on his activities in the Spartacist League; he resumed leadership of the group together with Rosa Luxemburg and published its party organ, the Rote Fahne ("red flag").

On 9 November, Liebknecht declared the formation of a "Freie Sozialistische Republik" (Free Socialist Republic) from a balcony of the Berliner Stadtschloss, two hours after Philipp Scheidemann's declaration of the "German Republic" from a balcony of the Reichstag.

On 31 December 1918 / 1 January 1919, Liebknecht was involved in the founding of the KPD. Together with Luxemburg, Leo Jogiches and Clara Zetkin, Liebknecht was also instrumental in the January 1919 Spartacist uprising in Berlin. Initially he and Rosa Luxemburg opposed the revolt but participated after it had begun. The uprising was brutally opposed by the new German government under Friedrich Ebert with the help of the remnants of the Imperial German Army and freelance right-wing militias called the Freikorps; by 13 January, the uprising had been extinguished. Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg were abducted by Freikorps soldiers, on 15 January 1919 with considerable support from Minister of Defense Gustav Noske, and brought to the Eden Hotel in Berlin where they were tortured and interrogated for several hours. Following this, Luxemburg was battered to death with rifle butts and thrown into a nearby river while Liebknecht was shot in the back of the head then deposited as an unknown body in a nearby mortuary.

That's not Karl Liebknecht, it's August Bebel.

ReplyDeleteThe photo of the younger Liebknecht does not resemble the bas relief. Check the photos of Bebel (head of the German Socialist party at the time the building went up) in Wikipedia to confirm this.