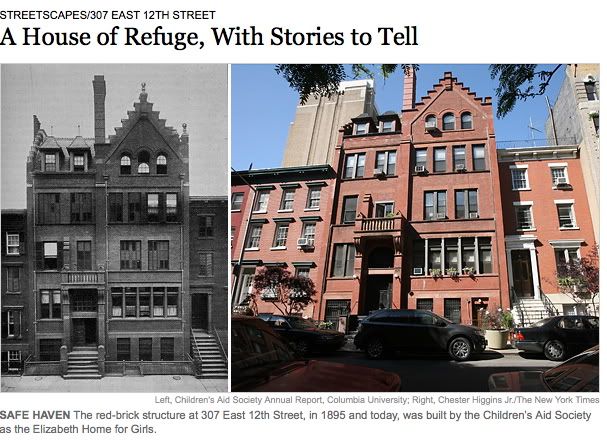

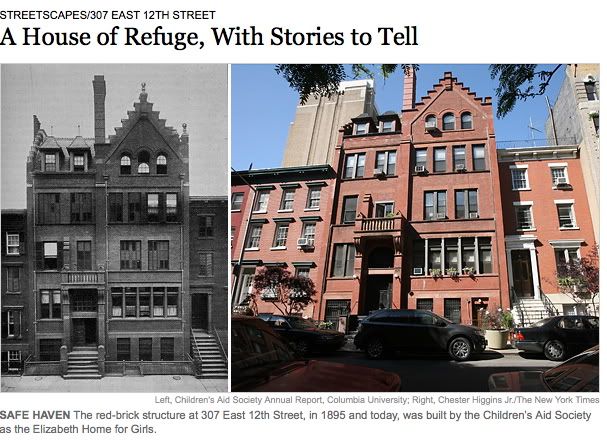

307 East 12th Street A House of Refuge, With Stories to Tell

An excerpt from a June 6, 2008 Streetscapes' column by Christopher Gray

An excerpt from a June 6, 2008 Streetscapes' column by Christopher GrayON a street of intensely varied architecture, the busy red brick structure at 307 East 12th Street still attracts confused curiosity. Tenement? Club? Institution? It is hard to tell. The building, one of Manhattan’s newest landmarks, has elements of all three. Built in 1892 as the Elizabeth Home for Girls, it housed several dozen young women rescued from abusive homes, offering them safe lodging, job training and healthy communal activities. The Elizabeth Home was built by the Children’s Aid Society, founded in 1853 by the Rev. Charles Loring Brace, part of a great wave of reform that swept over New York in the mid-19th century. Mr. Brace was concerned about the thousands of children, some orphans, some simply on their own, who made their way as best they could selling newspapers or matches, or surviving in gangs or through other activities. In 1863, he established a refuge for girls in an older building on St. Marks Place, and beginning in 1879 built a variety of entirely new structures for boys. The girls did not get their new building until 13 years later, when the Elizabeth Home opened as the last of 11 projects in Manhattan for the society. All were designed by Calvert Vaux of Vaux & Radford. .. Mr. Vaux’s building design in such cases usually conformed to a type: four stories high, fiery red brick, bearing a picturesque roof line and sited at midblock. (Another notable example, the Mott Street Industrial School, survives on Mott south of Houston Street.) The girls’ home, named after Elizabeth Davenport Wheeler and paid for by her children, had dormitories, classrooms, a lounge and six private rooms with names like Daisy, Pansy and Forget-Me-Not; there were 58 beds in all. It also had a washing and drying room: laundry was an important trade taught to the girls, along with typing and dressmaking. ......Some idea of the home’s residents can be gleaned from an article in The New York Times in 1887 — while they were still installed in their St. Marks Place building. Annie Brown, 28, was described as having been left on the streets by her parents as an infant. Although adopted, she was said to have run away three times and become obsessed with discovering her biological parents, constantly searching through municipal records. Finally, according to the article, she had a breakdown, shrieking in the dormitory on St. Marks until she could be restrained. The society’s annual report of 1893 mentioned one girl in particular, Bertie, who “sings softly about the house, and has a mania for cleaning up closets and corners.” In that year, the home took in 401 girls, who laundered 77,721 pieces of clothing.

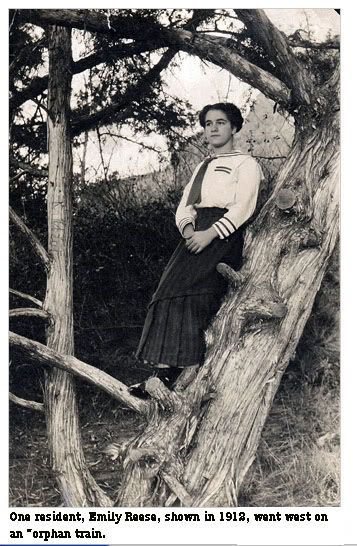

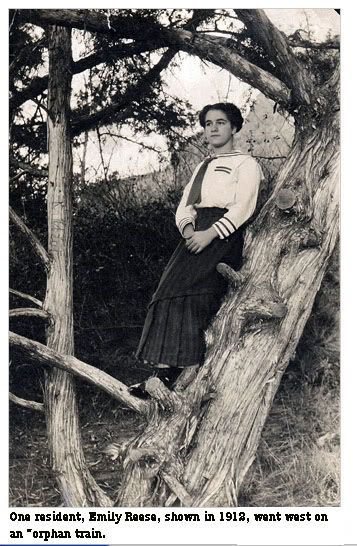

The girls listed in the 1900 census were mostly 14 to 21 years old and native to New York. These included Lillian Hadden, 16; Christiana Christian, 18; and Barbara Huff, 20. The course of their lives can be inferred from later census records. The 1910 census listed Christiana Christian as a convict at a reformatory in Newark. The 1930 census listed Lillian Hadden, 45, as married but with no husband present, living with her widowed mother, and Barbara Huff, 51, as a servant with a family. Both women were living in the Bronx. The story of yet another resident, Emily Reese, is the subject of a book by Clark Kidder, her grandson. “Emily’s Story — the Brave Journey of an Orphan Train Rider” reveals that Emily was born in Brooklyn in 1892, given up by her parents for reasons unknown and living at the Elizabeth Home in 1905. The next year she was one of thousands to go west on “orphan trains,” for adoption by farm families.

An excerpt from a June 6, 2008 Streetscapes' column by Christopher Gray

An excerpt from a June 6, 2008 Streetscapes' column by Christopher Gray

No comments:

Post a Comment