Cliff's uncle, Harry Rothman, was the principal of PS 87 at around the time these ladies went there

from the nytimes by Michelle V. Agins

As a young girl growing up on the Upper West Side in the early 1950s, Laurie Burrows Grad, the daughter of the playwright Abe Burrows, had every intention of becoming a Girl Scout until her mother put an end to it. “She let me be a Brownie, but then she found out that the Girl Scouts were segregated, and she couldn’t tolerate that,” Ms. Burrows Grad, a glass of wine in her hand, explained to a roomful of women last week. “But she didn’t think I’d understand that idea at that age. So she just told me that green wasn’t my color.”

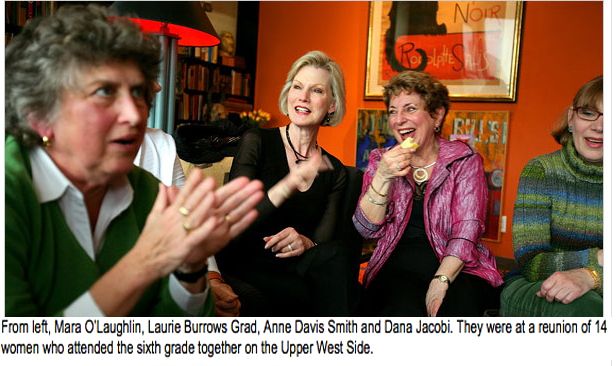

Her audience howled. Ms. Burrows Grad, 63, has surely dined out on that story dozens of times, but never to a more appreciative audience. The 13 other women relaxing in the room not only grew up with the same values in the same Upper West Side neighborhood, but most of them could easily picture her mother (“my mother, the Socialist, left wing nut case,” as Ms. Burrows Grad described her). As 11- and 12-year-olds, all of them had attended the same sixth-grade class — what was known at the time as a class for “intelligently gifted children” — at Public School 87 on West 78th Street, and most of them had even been members of that same Brownie troop. Once they’d split pineapple ice cream sodas at Schrafft’s and bugged each other’s older brothers for baseball cards. But with the exception of a few pairs who’d stayed in touch, none of the women had caught up since they graduated from sixth grade in 1956.

When several women, old friends from childhood, haven’t seen one another in more than 50 years — during which children were raised, careers stalled and were jump-started and personalities were all but reinvented — how do they begin to reconnect?

Sometimes they start with hair. “You became a redhead,” said Dana Jacobi, a cookbook author and Web editor, after embracing Barbara Goldberg, a furniture retailer. “We all became something,” Ms. Jacobi added.

below PS 87 today

Finding out what, exactly, had become of each of them was no small part of the pleasure of the reunion being held in the East Village loft of Jessica Weber, owner of a graphic design company and fellow P.S. 87 alumna, who had organized the event on a whim. Among their ranks: a biographer, several advertising and marketing executives, educators, retail entrepreneurs and decorators.

“It’s interesting how many of us went into so-called women-friendly fields,” Ms. Weber said. “If we were 10 years younger, there’d probably be a few more lawyers and bankers.”

Ms. Weber and her classmates may have been products of the ’50s, but for many, ambitions were paramount from the start, in an era before balance was a buzzword. They were all from “Jewish, solidly middle-class families with deep Manhattan roots,” as one woman put it, characterizing much of the neighborhood at the time. The expectations were high. “We all knew we were going to college,” said Mara O’Laughlin, the vice president for institutional advancement at Hobart and William Smith Colleges. Of the 14 women, they were surprised to learn, only eight had had children. The average number of husbands: around 1.5 (only three first marriages had not ended in divorce, and one of those is only a year old).

Entering college in 1962 and graduating in 1966, they represented a kind of bridge generation, fluctuating somewhere between Marjorie Morningstar (and yes, like that fictional heroine, many of them stopped traffic as they crossed Central Park West on horseback) and Joan Baez. “As a college freshman, I wanted to date a stockbroker,” said Lois Beekman, who now does marketing for nonprofits. “By the time I graduated, my boyfriend and I used to comb each other’s long hair and walk down Riverside Park holding daisies.”

Over the course of the evening, the confessions from the women covered failed marriages, physical infirmities, and numerous childhood infractions like dumping water down their apartment buildings’ mail chutes and enlisting the help of dad’s advertising agency for a submission to a student poster competition (the prize: escorting Eleanor Roosevelt when she spoke at the school).

Judging from the conversations that evening and the e-mail messages leading up to it, 50 years from now, current students at P.S. 87 won’t remember Hannah Montana or the great financial downturn of 2009 as vividly as they’ll recall some sushi joint on Broadway that had great yellowtail. On and on these 60-something women went about the delicacies of their youth: the cherry napoleons at Eclair, the hamburger with onions at P. J. Clarke’s, Gail Blumberg’s mother’s stuffed artichokes. Those they remembered as if it were yesterday. The details of Eleanor Roosevelt’s visit? “Who remembers!” said Ms. O’Laughlin, who’d won the poster contest.

The next day, all 14 women joined a tour of P.S. 87, about which they had little to say except that the linoleum had held up remarkably well. The long evening before — the instant intimacy, the shared memories — was what had made the reunion worthwhile for the women who’d flown in for the opportunity. (As for why there were no men invited, said Ms. Weber, ‘None of us were curious!’ ”) The women in their class gathered after the tour for lunch at the uptown Ruby Foo’s, looking, by the end, a little bit wistful, but not for the old bossy waiters at Fine & Schapiro’s or the school trips they took to the Wonder Bread factory in Queens. “It’s just that we let so much time go by before doing this,” Ms. Weber said. “The thread was reconnected.”

Harry Rothman's nytimes obituary from Sept 10, 1988

Harry I. Rothman, a principal in the New York City school system for more than 25 years, died of pneumonia Wednesday at Mount Sinai Hospital in Minneapolis. He was 82 years old and lived in Minneapolis.

Mr. Rothman began his career at the Bronx High School of Science in 1929. After teaching for several years, he was appointed principal of Public School 87, and later of P.S. 98, both in Manhattan.

He was also principal of Shaaray Tefila Sunday School for 30 years and taught writing at the New School for Social Research.

He is survived by a daughter, Ann Cohen of Minneapolis, and two grandchildren.

No comments:

Post a Comment