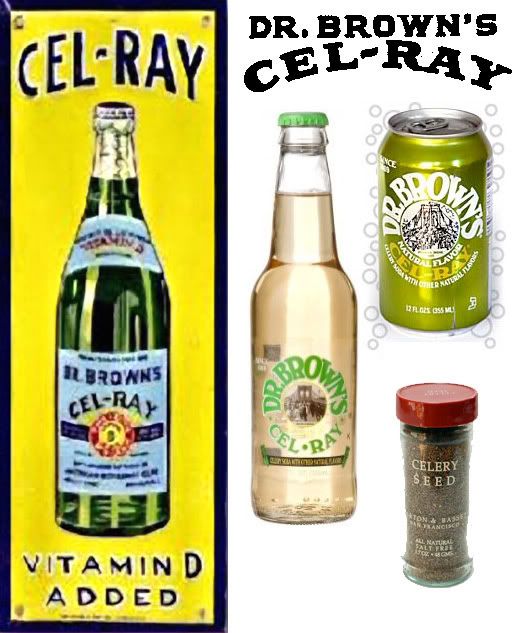

I substituted a Dr. Brown's Cel-Ray for the Dr. Brown's Cream Soda mentioned in the article

The Solerwitz's lived pretty long lives. The following data is from the Social Security Death Index:

William S. Solerwitz

SSN: 153-18-1696

Last Residence: 10019 New York, New York, New York, United States of America

Born: 8 Oct 1906

Died: 8 Jun 1997

State (Year) SSN issued: New Jersey (Before 1951)

Name: Abraham Solerwitz

SSN: 131-07-4597

Last Residence: 33139 Miami, Miami-Dade, Florida, United States of America

Born: 6 Jan 1909

Died: Apr 1985

State (Year) SSN issued: New York (Before 1951)

Charles Solerwitz

SSN: 125-07-9896

Last Residence: 11561 Long Beach, Nassau, New York, United States of America

Born: 27 Jan 1904

Died: Mar 1987

State (Year) SSN issued: New York (Before 1951)

Name: Max Solerwitz

SSN: 082-07-2144

Last Residence: 10023 New York, New York, New York, United States of America

Born: 24 Feb 1900

Died: Jan 1987

State (Year) SSN issued: New York (Before 1951)

Perhaps Charles eventually had a son named Jack (just a guess since the Jack Solerwitz mentioned below hailed from Long Island and Charles died in Long Island) He was also pretty much on the shifty side.

An excerpt from an article in 1989

LAW: AT THE BAR; Lawyer for striking air traffic controllers won back 60 jobs but suffered personal loss

By David Margolick

More than 11,000 air traffic controllers lost their jobs in their ill-fated strike of 1981. Jack Solerwitz, the lawyer who represented many of them, arguably lost even more.

At one time Mr. Solerwitz represented about 800 of the cashiered controllers. He fought to get them reinstated and won for 60 of only 100 controllers around the nation who got their jobs back. The process proved all-consuming and nearly consumed Mr. Solerwitz.

His marriage is on the rocks. Colleagues made off with pieces of his practice. He looks shabby and his office, in Mineola, L.I., has old newspapers, files and empty bottles of Coke and Dr. Brown's Cream Soda strewn everywhere. His copy of Learned Hand's ''Spirit of Liberty'' speech is falling out of the frame. His waiting room is empty.

And after a Federal court suspended him for one year for clogging its calendar with appeals it deemed frivolous, his livelihood is in jeopardy.

Mr. Solerwitz has paid the court $100,000 in fines. He has given another $100,000 to his lawyers, Alan and Nathan Dershowitz, and $30,000 to expert witnesses. His lawyers and the witnesses argued he had simply fought for his clients, a task taking precedence over his competing obligations as an officer of the court. But last week the United States Supreme Court declined to hear his case for lifting the suspension.

Mr. Solerwitz is by nature neither troublemaker nor rabble rouser. His clients are agents of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, drug law-enforcement officers and police officers. Nor, he says, is he much of an idealist. His hero is Bob Hope, whose signed photos hang on his office wall. But he was struck by the plight of the controllers, many of whom he feels were duped into a disastrous strike.

For four years, he devoted himself to them. ''I was the only lawyer who kept the doors open for them, and I thought I'd get a medal for it,'' he said. ''Instead, I was the one who drank the Kool-Aid.''

In January 1982 Rory Forrestal, the leader of a small group of dissident controllers, retained Mr. Solerwitz to represent him and 35 colleagues. The next morning 500 more controllers, disenchanted with their union's lawyers and impressed by Mr. Solerwitz, lined up outside his office. Eventually, there were clients from Florida to Minnesota to Alaska. He charged each one $3,000. Many didn't or couldn't pay.

The firm of Solerwitz, Solerwitz & Leeds mushroomed. Mr. Solerwitz hired 20 controllers and 20 Hofstra University law students for technical and logistical support. His wife (and law partner), who had just given birth to their fourth child, returned to work full time. Facing short deadlines, they blew out three Xerox machines churning out appeals.

They then lost pro forma proceedings before the Federal Merit System Protection Board for civil servants, and he presented the cases to the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit in Washington. The court ruled against the controllers in several cases it chose out of hundreds filed. It warned that only truly distinguishable cases could be appealed. Mr. Solerwitz ignored the warnings. Perhaps the Supreme Court would reverse; perhaps some political accommodation would be reached. And his clients wanted their cases in court.

The court said his briefs lacked merit, ignored authorities, even had the same typographical errors. It called his conduct ''flagrant and totally inexcusable abuse of the judicial process.''

An excerpt from a 1993 article

At the Bar; Twice stung by crooked lawyers, and twice saved by the client protection fund. By David Margolick

Before long, a check for $74,917 will arrive at Sarah Kiss's apartment in Far Rockaway, Queens. Then, at long last, the 32-year-old Ms. Kiss, a mortgage broker's representative and part-time makeup artist, will be able to buy some furniture and send her three children to summer camp.

She may also reflect on her horrific experiences with lawyers, which recently led The New York Law Journal to call her "New York's Unluckiest Client."

The New York Lawyers' Fund for Client Security, created to reimburse the victims of crooked lawyers, has done a brisk business in its 11-year history, paying out $29 million to 2,200 defrauded clients. But only one of them, Ms. Kiss, has had to come before the panel a second time, when her stolen money was stolen again by a second thief with a law license.

To some degree her story is a nightmarish aberration, like one of those tales of tornadoes hitting the same trailer twice. At the same time, it reflects a far more common, perpetual problem: the terra incognita ordinary people tread upon whenever they look for a lawyer.

In 1989, the lawyer who handled Ms. Kiss's divorce, Jack B. Solerwitz of Mineola, L.I., absconded with the $70,834 she received from the sale of her house required by the settlement. Ms. Kiss then hired a second lawyer, Bertram Zweibon of Manhattan. In 1990, with Mr. Zweibon's help, the fund compensated Ms. Kiss for most of her losses. But Mr. Zweibon promptly stole everything she had just recouped. "Aside from the fact that my ex was driving me nuts, all these guys were taking my money," she recalled.

It is in her religious tradition, said Ms. Kiss, an Orthodox Jew, to take people at their word. It is also, she thinks, in her stars. Asked how she could have judged legal talent so badly, she replied: "Maybe it's because I'm an Aries and I trust people. Don't you think it's a better way to be?"

But bitter experience, she concedes, has made her a bit warier -- a feeling, she said, that has spilled over to her children. "The latest line of the oldest one," she said, "is, 'Lawyers are liars.' "

Fiorello LaGuardia liked to say that when he made a mistake, it was "a beaut," and for Ms. Kiss this is doubly true. In New York legal lore, Mr. Solerwitz is the Babe Ruth of ripoffs, having been convicted of stealing more than $5 million in the 1980's. He is serving 5 to 15 years in prison for grand larceny.

"I didn't know any lawyers, and he was a very nice man," said Ms. Kiss, whose children were 3, 4 and 6 when she left her husband in 1987. "Someone finally wants to help you; you jump at it. What did I know? When you're dealing with a woman with three small babies, it takes a lot of chutzpah to do something like that."

Compared with Mr. Solerwitz, Mr. Zweibon, now serving one to three years, was a piker: he was convicted of stealing only $2 million, including $45,000 from the estate of his mother-in-law and $30,000 from Ms. Kiss's father, a rabbi. For Ms. Kiss, however, his betrayal was even greater, for Mr. Zweibon came highly recommended from friends in an insular, closely knit Orthodox Jewish community centered along Central Avenue in Far Rockaway.

"He convinced me to leave the money with him, so I did," she said. "He said it was safe there, it would be secure for my kids. 'You have a job, you're managing, you'll get your interest, leave it where it is! When you need it, you'll tell me.' So when I did I called him, and he never returned my calls.

"I felt raped. I live with a conscience every day. Just because he has a license to practice law, doesn't he have a conscience?"

No comments:

Post a Comment