Winds up the guy who has the chief writer for both the Life Of Riley and the People's Choice was Irving Brecher. He died recently at 94. In the 1920 census I found him at 2860 Crestwood Avenue in the Bronx. Irving's father, Marks, came to the U.S. in 1901. More than likely he probably started off on the LES.

from the nytimes

Irving Brecher, 94, Comedy-Script Writer, Is Dead, November 19, 2008, By BRUCE WEBER

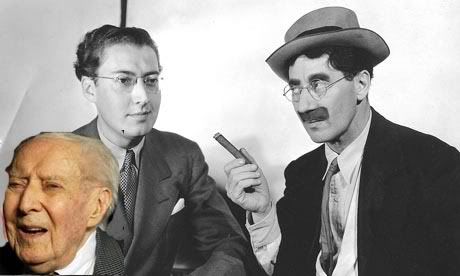

Irving Brecher, who wrote vaudeville sketches for Milton Berle, jokes for Henny Youngman, comedies for the Marx Brothers, a television series for Jackie Gleason and screenplays for movie musicals including “Meet Me in St. Louis” and “Bye Bye Birdie,” died on Monday in Los Angeles. He was 94.

His death was confirmed by Nell Scovell, a friend, who said Mr. Brecher had had a series of heart attacks last week.

Within the tribe of Hollywood gag writers, Mr. Brecher (pronounced BRECK-er) was a literary lion, a reflexive offerer of reactive jokes, a relisher of puns, a connoisseur of often topical, arch repartee. He once angered the film producer Daryl Zanuck, telling him the movie he had just made hadn’t been released; it had escaped.

“If I were any drier, I’d be drowning,” he had Groucho Marx saying, stuck in the rain in the 1939 film “At the Circus.” Always a tester of taboos, in the same film he had Groucho tease the guardians of Hollywood’s decency. In one scene, a mischievous vixen played by Eve Arden hides a billfold in her cleavage, and Groucho, wanting it back, says to the camera: “There must be some way of getting that money without getting in trouble with the Hays Office.” Groucho would later say it was the biggest laugh in the film. He and S. J. Perelman, asked to name the world’s quickest wits, listed Mr. Brecher along with George S. Kaufman and Oscar Levant.

Mr. Brecher received sole screenplay credit for two Marx Brothers films, a feat in itself. (The second was “Go West,” released in 1940.) He was nominated for an Academy Award for his screenplay for “Meet Me in St. Louis,” the Vincente Minnelli family musical set in the early 1900s, which became one of Judy Garland’s biggest hits, but only after Mr. Brecher talked her into making it by reading her the script. Garland had been afraid her co-star, Margaret O’Brien, was going to upstage her, Mr. Brecher explained to Hank Rosenfeld, his collaborator on a forthcoming autobiography.

“When I got to O’Brien’s lines, I would kind of throw them away,” he said. “Then I would emphasize what Judy’s character was doing.”

Mr. Brecher was the creator of the long-running radio series “The Life of Riley,” about an ordinary working-class schnook who causes no end of trouble for his family; it was played first by Lionel Stander and later, more famously by William Bendix. Mr. Brecher turned it into a feature film, with Bendix, in 1949, and a television series in the fall of the same year — making it arguably the first situation comedy on TV — and hired Jackie Gleason for the lead role of Chester A. Riley. The series lasted only until the following spring. But when it was reprised in 1953, with Bendix back in the title role (frequently uttering his signature line, “What a revoltin’ development this is!”), it stayed on the air until 1958.

The writer in Mr. Brecher had something of an affinity with Riley, an airplane riveter. During the writers’ strike of 2007, he made a video in which he urged the writers not to settle.

“Since 1938, when I joined what was then the Radio Writers Guild, I have been waiting for the writers to get a fair deal; I’m still waiting,” he said to the camera. He added: “As Chester A. Riley would have said, ‘What a revoltin’ development this is!’ But he only said it because I wrote it.”

Irving Brecher was born in the Bronx on Jan. 17, 1914, and he grew up in Yonkers. At 19, after a brief stint covering high school sports for a local newspaper, he took a job as an usher and ticket taker at a Manhattan movie theater, where he learned from a critic for Variety that he could earn money writing jokes for comedians. Knowing of Milton Berle’s reputation as joke-pilferer, he placed an ad in Variety, reading, in part: “Positively Berle-proof gags. So bad not even Milton will steal them.”

Berle himself hired him.

In 1937, he moved to Hollywood and began working on scripts for Mervyn LeRoy, head of production at MGM. He was an uncredited script doctor on “The Wizard of Oz,” leading Groucho Marx to call him “The Wicked Wit of the West.” (He took it as the title of his autobiography, to be published in January by Ben Yehuda Press.)

His film credits include “Shadow of the Thin Man” (1941), with William Powell and Myrna Loy; “Du Barry Was a Lady” (1942), with Lucille Ball, Gene Kelly and Red Skelton; “Yolanda and the Thief” (1945), starring Fred Astaire; and “Bye Bye Birdie” (1963).

Mr. Brecher’s first wife, Eve Bennett, died in 1981. He is survived by his wife, Norma, and three stepchildren.

In 1989, at Mr. Brecher’s 75th birthday party, Milton Berle both expressed his appreciation and extracted some revenge.

“As a writer, he really has no equals,” Berle said. “Superiors, yes.”

You can check out Irv's autobiography, The Wicked Wit of the West, over on Amazon. He was a true American original.

ReplyDeleteReb Yudel is right. The book is hilarious, moving and an invaluable record of one of the greatest wits of the last century. This century, too: view his video on UTube, talking about the 2007 writers strike. "What a revoltin' development this is," he said. "But he (William Bendix in 'The Life of Riley')only said it because I wrote it. I'm Irving Brecher. And I'm a writer." (Maybe not his exact words, but close.) Get THE WICKED WIT OF THE WEST and read about how Brecher wrote "Meet Me in St. Louis" -- and talked Judy Garland into doing the film. He wrote seven musicals for MGM, including the ever-popular "Bye Bye Birdie."

ReplyDeleteA quote in the front of the book says it's "like spending 'Tuesdays with Morrie' reading 'Krapp's Last Tape.' To which I add ... "with humor."