Wednesday, May 30, 2012

The Baudelaires of East Broadway

Ruth Wisse will be at the Eldridge Street Synagogue on June 3 as part of a Yiddish Writers Tribute. Reuben Iceland and Anna Margolin, members of the Di Yunge, lived in Knickerbocker Village at 18 Monroe Street

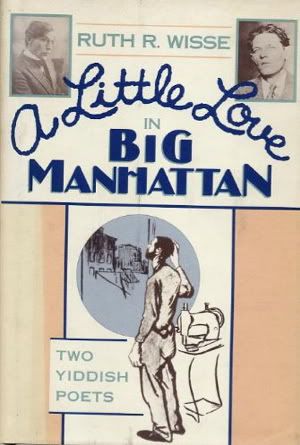

excerpts from a Commentary Magazine review of "A Little Love in Big Mahattan: Two Yiddish Poets."

The story Ruth R. Wisse tells in her latest book is, like the poem from which she takes her title, ironic and bittersweet. It is the story of a group of young Yiddish-speaking immigrants in turn-of-the-century New York who lived for poetry. Their brief, doomed movement to fashion a purified Yiddish aesthetic, one which was committed not to any political or social ideal but to language itself, began in 1907 and was known as Di Yunge (“The Young”). In the two decades between the first major wave of Jewish immigration in the 1880′s and the years when these poets arrived, Yiddish culture in America had already undergone a number of changes. The first Yiddish literature, typified by the “sweatshop school” of poetry, was didactic and blunt; it addressed itself entirely to the requirements of the working-class population, depended on a close alliance with the Yiddish press, and was cut off from the folk traditions of the prose masters—Sholem Aleichem, Men-dele, Peretz—who were then writing their best works in Russia and Poland. The sweatshop poets, responding to a totally unfamiliar tenement and factory existence, engineered a kind of literary expression that suited the needs of their uprooted, bewildered audience. Their poetry was little more than a bald testimony to this community’s hard new life.......Perhaps the example of Yunge poetry which manages best to incorporate all these high-minded ideals is Mani Leib’s “Shtiller, shtiller” (“Hush, hush”), a poem about waiting for the messiah, which opens this way

Hush and hush—no sound be

heard.

Bow in grief but say no word.

Black as pain and white as death,

Hush and hush and hold your

breath.

One by one they declared their devotion to this pure, self-contained aesthetic: Mani Leib, Reuben Iceland, Zishe Landau, Moishe Leib Halpern. Barely twenty, fresh from various parts of the Jewish Pale, working endless hours in bootmaking factories or as window washers, they gathered at night in the cafes to discuss the French symbolists and Walt Whitman. They were lucky to steal a few moments alone in a crowded, noisy apartment, these Baudelaires of East Broadway, to write longingly of stillness, quiet, trees, snow. To their heated debates they brought the zeal of the formal religious practices they had all but abandoned. They called themselves “a new kind of minyan”; for them, poetry was like the promise of the Sabbath or of Mani Leib’s breathlessly awaited messiah—it brought the redemption of the world into closer view. They saw themselves as dandies, as aesthetes, with “their elegant canes, their long hair and their wide, sweeping hats,” but what one notices first about them is how close to the shtetl they still were, and how young, how full of books and spite and cheerfulness and strength.

No comments:

Post a Comment