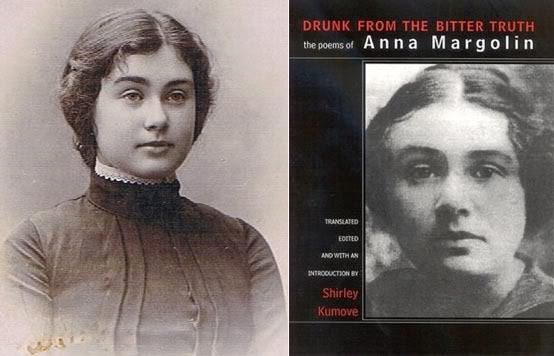

Rosa Lebensboim, better known by her pen name of Anna Margolin, is regarded by literary critics as one of the finest early twentieth-century Yiddish poets in America. Her poetry, translated by Adrienne Rich, Kathryn Hellerstein, and Marcia Falk, among others, appears in many Yiddish poetry anthologies in English. Captivating, temperamental, and intellectually gifted, Anna Margolin influenced the work of several major writers and thinkers of her time....... She joined the staff of the newly established daily Der Tog in 1914, and became a member of the editorial board until 1920. At Der Tog, she wrote a weekly women’s column entitled “In der Froyen Velt” [In the women’s world] and traveled in Europe as a correspondent reporting on women’s issues. During this time, she wrote several articles supporting the suffrage movement. In the offices of Der Tog, Margolin met her second husband, Hirsh Leib Gordon. When Gordon left for service in World War I, they became estranged, and Margolin became involved with Yiddish writer Reuben Iceland. Iceland was instrumental in encouraging her writing of poetry, and Margolin, in turn, had an impact on his writing. They became lifelong companions. Margolin used many pen names during her writing career. Beginning in 1909, she wrote short stories under the names Khave Gros and Khane Barut. She signed some of her journalistic work as Sofia Brandt and later as Clara Lenin. When she began to publish poems in the early 1920s, she used the pseudonym Anna Margolin, and then published all her poetry under this name.

Showing posts with label 18 Monroe Street. Show all posts

Showing posts with label 18 Monroe Street. Show all posts

Saturday, May 26, 2012

Who's Who In Knickerbocker Village History: Anna Margolin, 1940 Census

an excerpt of a biography by Sarah Silberstein Swartz:

Who's Who In Knickerbocker Village History: Reuben Iceland, 1940

reuben iceland

In 1940 Reuben Iceland and his wife Anna Margolin were living at 18 Monroe Street. Reuben's real name was Ruven Ayzland

An excerpt from From Our Springtime

I don’t remember what year I met Zishe Landau. It is also unclear to me whether it was late in autumn or early in spring. But I well remember that it was in the evening on Canal Street in front of the old Drukerman’s bookstore, that the evening was cold, misty and muddy, and that I wore a heavy winter coat. All the passersby wore heavy winter coats, and everyone in the little group of young writers who stood in front of the bookstore, waiting for a new periodical that was supposed to have been brought from the printers, wore heavy coats. But the thin, blond boy with the big blue eyes, who was introduced to me as Zishe Landau, wore a light, narrow, leather-colored summer topcoat buttoned tightly over a pointy belly. For those who knew the later broad and hefty Landau, it might be hard to imagine that in his nineteenth or twentieth year he was a thin, almost sickly boy, just as they might be unable to imagine that Landau used to go dressed as a dandy, in tight clothes, a stiff collar and a derby. In this last respect, though, he was not an “only child.” All of us in those years had notched rings on our foreheads from the hard round hats we wore. […] Like a lot of beginners who have not yet found their own voice, I sang, perhaps without realizing it, with an alien voice, and used poetic expressions that others before me had coined. Like a lot of beginners, I did not yet know that even the most powerful experiences and the deepest feelings do not in themselves make a good poem. Only later, when one becomes richer artistically, one discovers – often through great pain – the secret: that much more than impressions, experience, and sensitivity, one has to have expression. The best words in the best order, as Coleridge required. This means tone, rhythm, and form, valid only for a given poem and not for any other.

Labels:

18 Monroe Street,

1940 census,

Reuben Iceland,

who's who

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)