SCRN 120 - History of U.S. Film Since 1950 The history of post-WWII American cinema is the story of an ongoing series of adjustments to (or developments within the context of) instability in postwar film business: film noir, 3-D, biblical epics, blockbusters, art film influences, “new blood” from TV and film schools, Black filmmaking, revisionist genre films, high-concept filmmaking, etc. Further complicating this process of adjustments, cinema was overlaid onto, and consequently influenced by, the political turmoil within American society in general: the “Red Scare,” the Vietnam War, the emergence of a mass counterculture, the antiwar movement, Watergate, Reaganomics, the end of the Cold War and increasingly vocal demands by women and minorities for social equality (and media representation).One of the films she viewed was Pickup On South Street. I've talked about the film and Sam Fuller several times here and I always assumed some scenes were filmed on location. Evidently according to this blogger they weren't. However, in part 2 of the film embedded above, it looks like at about the 5:36 mark a shot is filmed near the Brooklyn side of the Manhattan Bridge. I can make out other NYC shots in other scenes, but evidently the outdoor views from Widmark's dockside shack, towards the end of the clip above, are fake.

Showing posts with label samuel fuller. Show all posts

Showing posts with label samuel fuller. Show all posts

Friday, January 27, 2012

Revisiting Pickup On South Street

My daughter Emma is taking a really interesting film class at Clark University with a Professor Michael Siegel

Monday, April 19, 2010

The Lost World Of Sam Fuller

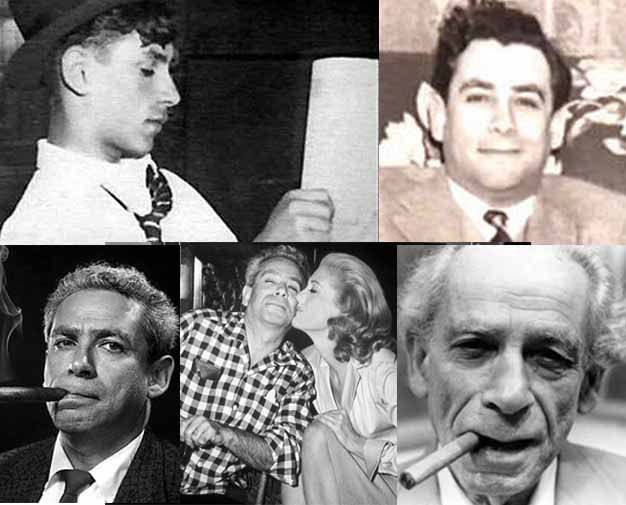

Fuller walked the streets of the Fourth Ward and was a newsman in addition to being a great director. Above he speaks about the making of Pickup On South Street. Below from one of several prior posts on Fuller

He became a crime reporter in New York City at age 17, working for the New York Evening Graphic. He broke the story of Jeanne Eagels' death. He wrote pulp novels and screenplays from the mid-1930s onwards. Fuller also became a screenplay ghostwriter but would never tell interviewers which screenplays that he ghost-wrote explaining "that's what a ghost writer is for".

Thursday, June 18, 2009

Sam Fuller's Park Row

from tcm by John Sayles

At age 12, long before he began the career that would make him one of the most discussed maverick film directors in American pictures, Samuel Fuller got his first job as a copyboy on the New York Journal. At 17, he was a crime reporter for the San Diego Sun. This early background may partially explain why Fuller's films have always had a certain tabloid feel to them. But Park Row (1952) was the movie that really expressed his great affection and respect for the newspaper business. And in lovingly recreating every detail of the street in Lower Manhattan where he worked as a kid, a turbulent neighborhood between the Brooklyn Bridge and the Bowery, Fuller created a historically rich tribute to the New York of the late 19th century.

Park Row could have turned out to be nothing like Fuller's plans, if he hadn't taken the reins himself. Fuller had been under contract for a few years to 20th Century Fox and recently completed two very successful war stories for the studio, The Steel Helmet (1951) and Fixed Bayonets (1951). Studio boss Darryl F. Zanuck wanted Fuller to overhaul his script from the top down, starting with the title. The studio once had a major hit with a period adventure/romance about the Great Fire In Old Chicago (1937) and wanted Fuller to call his picture "In Old New York." And to the young director's horror, Zanuck was demanding it be turned into a musical with Dan Dailey and Mitzi Gaynor. Determined to do it his own way, Fuller sunk every penny he had - a considerable amount earned from the war flicks - into an independent production so he could call all the shots. Most of the money went for the set, which Fuller insisted show the street exactly as it was in 1886. Against the protests of his designers, he called for reproductions of the buildings on Park Row to be four stories high, even though the top floors would likely never even be seen on camera. "But I had to see it all," Fuller said. "I had to know everything was there, exact in every detail."

Fuller's passionate attention extended to the plot, the story of a dedicated journalist who manages to set up his own paper, one that will be free of corruption and report the truth. The venture is an instant success but attracts increasing opposition from one of the bigger papers and its heiress owner. Although he fancies the young woman, the newsman resists her attempts to either drive him out of business or have his paper merge with her company. He perseveres in his mission and holds onto his ideals; eventually, she comes to see it his way. Besides showing the daily details of running a paper, Fuller also filled the film with wider historical interest, such as the groundbreaking invention of the Linotype machine and the erection of the Statue of Liberty. For a Fuller film, the story and its lead character, newsman Phineas Mitchell, are remarkably noble and idealistic, showing little of the filmmaker's typical dark cynicism and moral ambiguity, opting instead for an utterly reverent view of the profession. But it is clearly a Fuller film, not only in the passion he brings to the material but in his frenetically physical directorial style.

Fuller did his best to make his gamble pay off. He opened Park Row in a big way at Graumann's Chinese Theater in Los Angeles, and it was a critical success. But he lost everything except the "cigar money" he put aside. Without any known stars to lure audiences, the public stayed away. As the heiress, Mary Welch appeared for the first and only time on film. She died six years later at the age of 36. The best-known cast member, in the role of Mitchell, was Gene Evans, with five-years of bit parts and a couple of featured roles in Fuller's war films to his credit. Evans, who spent most of his later career on television, made two more films with Fuller, and later stated that the director made a number of technical innovations on Park Row (which was shot in only a couple of weeks), including his use of the crab dolly, an elaborate, hydraulically operated wheeled platform that allows a combination of camera movements in any direction.

Fuller liked long takes, and his actors sometimes had to learn ten pages of dialogue for one shot. "He would lay out these long scenes, and move the camera around and move in and move back and move all around you, and just go on shooting until he ran out of film," Evans told Lee Server for the book Sam Fuller: Film Is a Battleground (McFarland & Co., 1995). The actor also said Park Row was the hardest picture he ever worked on. He related a story about Fuller talking him through a fight scene the director wanted to film in one long take from beginning to end. At one point Fuller told Evans to "roll underneath the wagon and fight over to the other side." What wagon, Evans wondered; the wagon that's going to be coming down the street, Fuller replied. "That Sammy, you had to be careful with him or you could get hurt," Evans said.

Who's Almost Who In Knickerbocker Village History: Sam Fuller

If you read through his autobiography you can see that his formative years were spent hanging out either in, or very close to, the Fourth Ward, as a newsboy and then as a teen reporter.

from Luc Sante

Samuel Fuller had ink in his veins, just like the hero of his 1952 newspaper epic, Park Row. After all, he started working as a copy boy when he was fourteen or so, and at seventeen he was the youngest crime reporter in the country, employed by the most daring and scurrilous tabloid America has ever seen, the New York Evening Graphic. When that paper folded (under the combined impact of a number of libel suits), he moved to California and soon began supplementing his salary by writing film scripts, selling his first in 1936, when he was just twenty-four. Five years later he was in the movie business full-time, and he directed his first picture, I Shot Jesse James, in 1949, not long after he got out of the service. In Hollywood he was clearly drawing on another part of his brain—he was a wildly visual and visceral filmmaker, and one of the great masters of the moving camera—but he never shed his reportorial instincts. He knew how to sell a story as well as tell one, how to hit hard and not let go. Every one of his movies has a built-in banner headline.

Pickup on South Street has a nominal subject as timely as any in the morning paper in 1952—PICKPOCKET HEISTS RED SPY MOLL––although today we might be more inclined to see it as PICKPOCKET FINDS LOVE, CHEATS DEATH. The Commie angle, besides being practically de rigueur for Hollywood that year, was a surefire means of injecting fear and trembling into the proceedings, by introducing a faceless, inhuman evil to contrast with the peccadilloes of the workaday American crook. That the picture is barely political can be demonstrated by the fact that, in France, where the Communist Party was a significant presence nobody wanted to offend, Pickup was released as Le Porte de la drogue—the villains became drug smugglers—with changes made only to the dubbed dialogue. What is at stake, after all, is nothing as high-flown as The American Way (“Are you waving the flag at me?” pickpocket Skip McCoy asks the FBI agent grilling him); rather, it is the possibility of a force so morally alien that, like the child molester in Fritz Lang’s M, the law and the underworld can be united, however briefly, against it.

McCoy is played by Richard Widmark, whose face could illustrate the dictionary definition of insolence. One look at him and you don’t even need the backstory to know why the cops want to send him up the river for good. Although he went on to play a wide variety of characters in his career, he was initially typed by his screen debut, which was also his first starring role, in Henry Hathaway’s Kiss of Death (1947), in which he kicks an old lady down the stairs. Here it is the old lady who nearly does him in, although their relationship is complex—she is, for all dramatic intents and purposes, his mother. Playing the part is the inimitable Thelma Ritter, who was unsurprisingly nominated for an Oscar for the role (it was the fourth of her six nominations in a twelve-year span; she never won). Ritter, only nine years older than Widmark, took the stereotypical Apple Annie character and over the course of her career made a Russian novel out of it. Here she is pathetic, cold-blooded, kittenish, stalwart, cunning, and tender, sometimes all at once. The love interest is supplied by Jean Peters, who is awe-inspiringly ripe—you imagine wardrobe having to gaffer-tape her dress every morning, to keep her from bursting out of it. Peters may not have been the greatest line-reader who ever lived, but she exudes sex so palpably, you can smell the pheromones. (She lost the fifties erotica sweepstakes to the forces of blondeness, alas, and gave up and married Howard Hughes.)

The locations are few but well chosen. A street, a subway station, a Chinese restaurant, a precinct-house office, an apartment (with that forgotten urban-thriller resource, the dumbwaiter)—put them together and presto! you have New York City and its teeming masses. Richard Widmark’s home is something else again, though: a bait-and-tackle shack on stilts, connected to South Street by a swinging bridge. It seems like a preposterous idea today, when New York’s function as a port has been all but erased, but (although I could almost swear I’ve seen a Berenice Abbott photograph of it from the 1930s) it was close to preposterous then, too. The shack is a bubble cantilevered off the tip of the material world, the bridge leading to it passing through the wall of sleep. In the midst of a zillion urban-grit signifiers, the shack cues viewers to the numerous fantasy elements of the story, not least the Red spy subtheme, but also the crooks themselves, who come from The Threepenny Opera by way of Damon Runyon. The shack is the beyond, but given that it is a real shack, roughly carpentered and battered by weather, it is also—what might be Fuller’s heraldic device—the embodiment of contradiction.

Fuller is crude and subtle, blatant and deep, unschooled and spilling over with ancient lore, harsh and plaintive, cynical and so attuned to complicated human emotions, you can’t accuse him of being merely sentimental. Pickup on South Street, it follows, is a penny dreadful with a hundred layers of felt meaning—the kind you register subcutaneously, without requiring professors to dissect and explicate it. If film noir is a genre in which tin-pot crimes are merely the outer manifestations of the churning unconscious, then Pickup on South Street is quintessential noir. Like so many of the worthwhile products of the American 1950s, it is a work of reverberating complexity, wrapped up to look like a candy bar.

Wednesday, June 17, 2009

Sam Fuller Talks About Pick Up On South Street

From 1982: Samuel Fuller talks pickpockets, Zanuck, Dwight Taylor, New York subways, set and story construction, writing with the camera -

It's safe to say that Sam Fuller had cahones

Samuel Fuller (August 12, 1912 – October 30, 1997) was an American screenwriter and film director known for low-budget genre movies with controversial themes. He was born Samuel Michael Fuller in Worcester, Massachusetts, the son of Benjamin Rabinovitch, a Jewish immigrant from Russia, and Rebecca Baum, a Jewish immigrant from Poland. After immigrating to America, the family's surname was changed to "Fuller". At the age of 12, he began working in journalism as a newspaper copyboy. He became a crime reporter in New York City at age 17, working for the New York Evening Graphic. He broke the story of Jeanne Eagels' death. He wrote pulp novels and screenplays from the mid-1930s onwards. Fuller also became a screenplay ghostwriter but would never tell interviewers which screenplays that he ghost-wrote explaining "that's what a ghost writer is for".

During World War II, Fuller joined the United States Army infantry. He was assigned to the 16th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division, and saw heavy fighting. He was involved in landings in Africa, Sicily, and Normandy and also saw action in Belgium and Czechoslovakia. In 1945 he was present at the liberation of the German concentration camp at Falkenau and shot 16 mm footage which was used later in the documenatary Falkenau: The Impossible. For his service, he was awarded the Bronze Star, the Silver Star, and the Purple Heart.[1] Fuller used his wartime experiences as material in his films, especially in The Big Red One (1980), a nickname of the 1st Infantry Division.

Pick Up On South Street: "What do I know about commies-I just don't like them"

from wikipedia. btw Thelma Ritter and Sam Fuller are headed towards "Who's Almost Who Distinction"

Pickup on South Street is writer-director Samuel Fuller's 1953 film noir released by the 20th Century Fox studio. The film stars Richard Widmark, Jean Peters and Thelma Ritter.

In June 1954, Ritter co-starred alongside Terry Moore and Stephen McNally in a Lux Radio Theatre presentation of the story. 20th Century Fox remade the picture in 1967 as The Cape Town Affair, directed by Robert D. Webb and starring Claire Trevor (in the Thelma Ritter role), James Brolin (in his first leading role), and Jacqueline Bisset.

Widmark plays Skip McCoy, a pickpocket who steals Candy's wallet, which contains a microfilm of top-secret government information. This sets off a frantic search for McCoy by the police and other parties interested in securing the microfilm.

Darryl F. Zanuck showed Fuller who was then under contract to 20th Century Fox a script by Dwight Taylor called Blaze of Glory about a woman lawyer falling in love with a criminal she was defending in a murder trial. Fuller liked the idea but knew from his previous crime reporter experience that courtroom cases take a long time to play out. Fuller asked Zanuck if he could write a story of a lower criminal and his girlfriend that he originally titled Pickpocket but Zanuck thought the title too "European". Fuller had memories of South Street from his days as a crime reporter and came up with his new title. Fuller met Detective Dan Campion of the New York Police Department to research the background material of his story to add realism, with Fuller basing the role of Tiger the police detective on Campion who had been suspeneded without salary for six months for manhandling a suspect.

Fuller turned down many actresses for the lead role including studio favorite Marilyn Monroe, Shelly Winters, Ava Gardner who looked too glamourous, Betty Grable, who wanted a dance number written in, and initially Jean Peters who he didn't like when he saw film of her in Captain from Castile. With only a week to go before the film started, Fuller saw Peters walk into the studio's commissary whilst having lunch. Fuller noticed Peters walked with a slightly bow legged style that many prostitutes did. Fuller was impressed with Peters intelligence, spunkiness, and different roles at the studio when he tested her the Friday before shooting started on the Monday. When Betty Grable insisted on being in the film and threatened problems, Fuller promised to walk off the film. Peters was restored.

In August 1952, the script was deemed unacceptable by the Production Code, by reasons of "excessive brutality and sadistic beatings, of both men and women." The committee also expressed disdain for the vicious beating of the character "Candy", on the part of "Joey." Although a revised script was accepted soon after, the studio was forced to shoot multiple takes of a particular scene in which the manner of Jean Peters and Richard Kiley frisk each other for loot, was too risqué.

The French release of the movie removed any reference to spies and microfilm in the translation. They called the movie Le Port de la Drogue (Port of Drugs). The managers of 20th Century Fox thought that the theme of communist spies was too controversial in a country where the Communist Party was still hugely influential.

When the film was released, Bosley Crowther wrote, "It looks very much as though someone is trying to out-bulldoze Mickey Spillane in Twentieth Century-Fox's Pickup on South Street, ...this highly embroidered presentation of a slice of life in the New York underworld not only returns Richard Widmark to a savage, arrogant role, but also uses Jean Peters blandly as an all-comers' human punching-bag. Violence bursts in every sequence, and the conversation is slangy and corrupt. Even the genial Thelma Ritter plays a stool pigeon who gets her head blown off...Sensations he has in abundance and, in the delivery of them, Mr. Widmark, Miss Peters, Miss Ritter and all the others in the cast do very well. Murvyn Vye, as a cynical detective, is particularly caustic and good, and several other performers in lesser roles give the thing a certain tone.

FBI director J. Edgar Hoover had lunch with Fuller and Zanuck and said how much he detested Fuller's other work and especially Pickup on South Street. Hoover objected to Widmark's unpatriotic character especially his line "Are you waving the flag at me?", the scene of a Federal agent bribing an informer and other things. Zanuck backed Fuller up, telling Hoover he knew nothing about making movies but removed references to the F.B.I. in the film's advertising.

Labels:

samuel fuller,

south street,

thelma ritter,

Ward 4

Tuesday, March 24, 2009

Pick Up On South Street

We mentioned this movie before. At that time only the trailer was on youtube, now (above) there's a more extended clip. Maybe Mr. Golden scored a good pickup on South Street when he swapped properties.

Labels:

movies,

samuel fuller,

south street,

Ward 4

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)