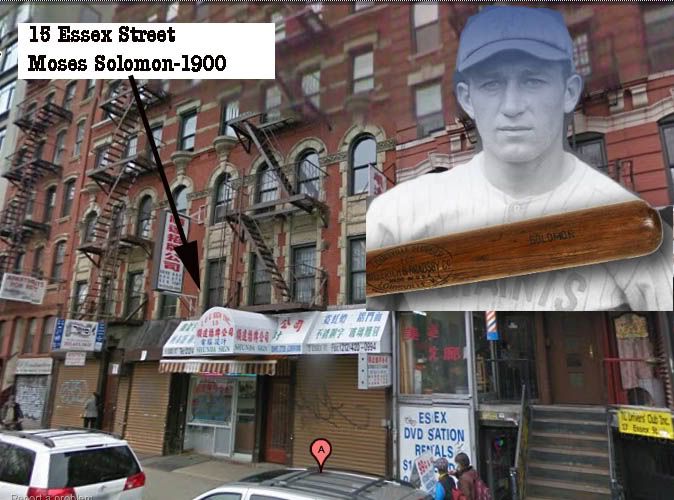

Moses Solomon was born on December 8, 1900 in New York City. He was the son of Russian immigrants, Benjamin and Anna Solomon. The elder Solomons were married in Russia in 1884 and came to the United States in 1891. They had eight children in all and Moses was the fifth of the eight. In 1906, the family moved to Franklin, Ohio and Benjamin worked for a junk dealer. Moses also worked for the dealer and is listed in the 1920 census as a time keeper for the dealer. A year later, Moses played baseball for the Vancouver Beavers in the Pacific Coast International League. He played in 115 games and batted .313 with 13 homers. Not bad for a first year in professional ball. He only played in a few games in 1922 but still batted .303. But it was 1923 that would make him a legend. By 1923, he had signed to play for the Hutchinson Wheat Shockers in the Southwestern League, a Class C league. He played mostly first base for the Wheat Shockers and had one of the most memorable seasons in minor league history. In 134 games, he batted 527 times, piling up 222 hits for a .421 average. He hit 40 doubles, 13 triples and 49 homers. The 49 homers set a minor league record and only the great Babe Ruth had more in professional baseball. McCarthy heard of Solomon's exploits and amidst much hoopla, purchased his contract and brought him to the Giants in September of 1923. He made his major league debut on September 30 and played two games. In eight at bats, he had three hits including a double and drove in a run. It would be the only two games he would ever play in the major leagues. The Giants found out about an aspect of Solomon's game that would prove to be his undoing. He couldn't field. The same minor league season where he set the record for home runs, he made 25 errors. He made an error in the two games he played in the outfield for the Giants. He was the Ron Bloomberg of his time. All hit, no field. Moses Solomon continued after the 1923 season to bang around the minor leagues. He played through 1929 and batted over .300 three times, but his total home run output of all those seasons did not come close to totaling as much as his 49 in 1923 alone. One source indicates he also played football, but no record can be found as such. By 1930, he is listed in the census as being back in Franklin, Ohio with his wife, Gertrude and two young children. His occupation is listed as, "Agent." His Wiki page states that he went into real estate and did quite well. The Rabbi of Swat died in Miami, Florida in 1966. Moses Solomon (or Mose) only played two games in the major leagues, but not many people could state that his career ended with a .375 average. Imagine if the guy with the .313 minor league career batting average could have caught the ball. His minor league record of 49 homers was broken in 1924 by Clarence Kraft who hit 55. Kraft didn't hold the record long himself as a guy named Tony Lazzeri (you may have heard of him) hit 60 in 1925.

Showing posts with label baseball. Show all posts

Showing posts with label baseball. Show all posts

Saturday, November 12, 2011

Who's Almost Who In Knickerbocker Village History: Moses Solomon

About Moses from passion4baseball:

Thursday, June 2, 2011

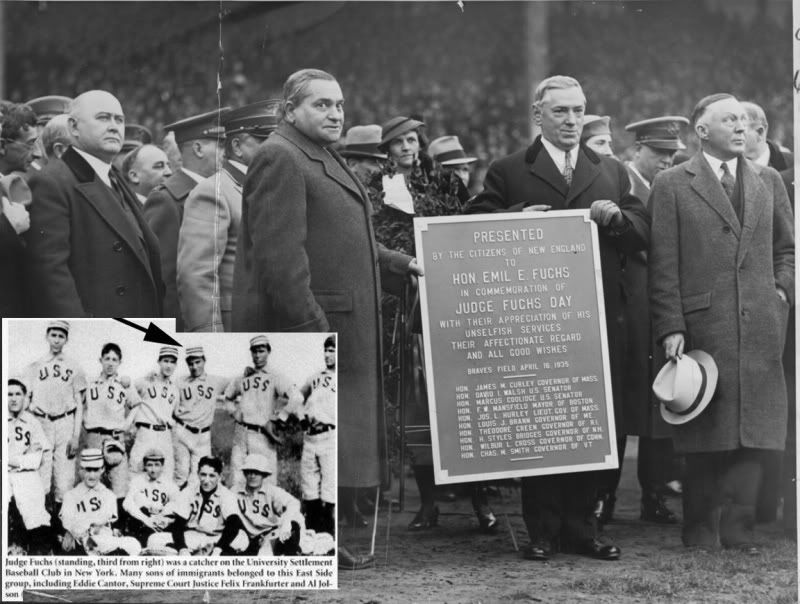

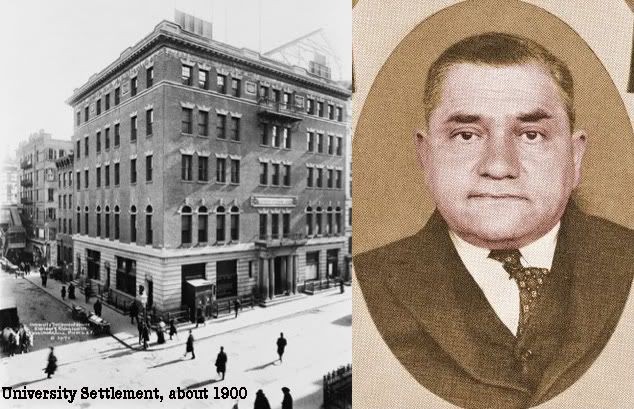

Another Jewish MLB Figure From The LES: Emil Edwin Fuchs

Fuchs played for the University Settlement team.

Emil Edwin Fuchs (17 April 1878 in Hamburg, Germany - 5 December 1961 in Boston, Massachusetts was a German-born American baseball owner and executive.

Fuchs was the attorney for John McGraw's New York Giants when he bought the Boston Braves with Christy Mathewson and James McDonough; the team struggled with financial problems throughout their ownership. After Jack Slattery quit as manager, Fuchs hired Rogers Hornsby to manage the rest of the 1928 season. He then sold Hornsby to the Chicago Cubs and managed the team himself, finishing in last place. The Philadelphia Phillies loaned Fuchs $35,000 to keep the Braves solvent.

By 1935, he was in such dire straits, he could not afford the rent on Braves Field. When he learned that Babe Ruth's days as a New York Yankee were numbered, Fuchs bought the slugger from Jacob Ruppert. Ruth was named vice-president and assistant manager of the Braves, and promised a share of the profits and a possible part-ownership. When he realized that Fuchs was broke and was using him as a last-ditch effort to revive his fortunes, Ruth announced his retirement on May 27. Soon afterward, Fuchs sold the team.

Emil Fuchs graduated from New York University Law School, and became a magistrate for New York City from 1915 to 1918. He was an attorney for the New York Giants for a time, and became friends with John McGraw. He was owner of the Boston Braves from 1923 to 1935, paying $550,000 for the team, while being $300,000 in debt when he sold. He managed the club in 1929 as well. Fuchs brought Babe Ruth back to Boston in 1935, the last season for both of them.

After selling the team, Fuchs resumed his law practice in Brookline, MA and paid off all his debts.

Friday, May 27, 2011

Thursday, May 5, 2011

Another Jewish MLB Player From The LES: Jonah Goldman

Jonah Goldman was born on Wednesday, August 29, 1906, in New York, New York. Goldman was 22 years old when he broke into the big leagues on September 22, 1928, with the Cleveland Indians. He died in 1980. For more on Jonah

Tuesday, May 3, 2011

The First Great Jewish Ballplayer: Lipman Pike, Part 2

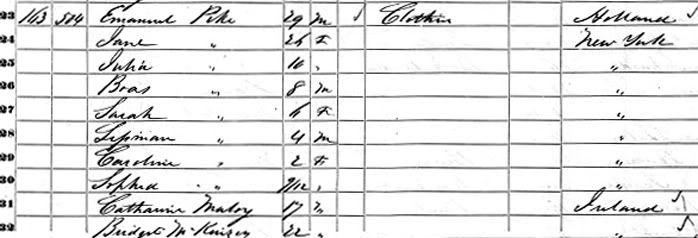

Above is the Pike family census from 1850. Lipman was 5 years old. It's somewhere in the fourth ward but no address is given. The mystery will soon be solved.

More on Pike from his wiki page

More on Pike from his wiki page

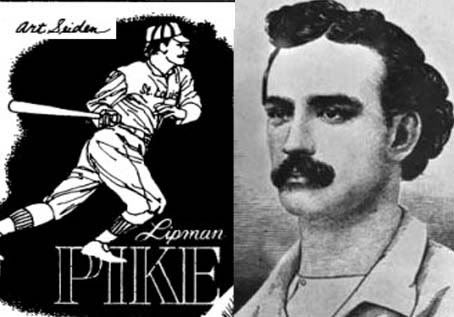

Lipman Emanuel "Lip" Pike (May 25, 1845 – October 10, 1893) was one of the stars of 19th century baseball in the United States. He was the first player to be revealed as a professional (meaning he was paid money to play), as well as the first Jewish ballplayer. His brother, Jay Pike, played briefly for the Hartford Dark Blues during the 1877 season.

His family was of Dutch background, and his father was a haberdasher. Pike was one of the premier players of his day. He was a great slugger and one of the best home run hitters of his day, so much so that stories about balls he hit were told for quite some time after he stopped playing.

Pike first rose to prominence playing for the Philadelphia Athletics, whom he joined in 1866. He brought an impressive blend of power and speed to the team, hitting many home runs as well as being one of the fastest players around. He was a star who in one game hit 6 home runs; the final score was 67-25.

However, it was soon brought to light that he and two other Philadelphia players were being given $20 a week to play. Since all baseball players were ostensibly amateurs (though many were, like Pike, accepting money under the table), a hearing was set up by the sport's governing body, the National Association of Base Ball Players. In the end, no one showed up to the hearing, and the matter was dropped. By 1869, the Cincinnati Red Stockings became the first openly professional team, and Pike's hearing, farcical as it seems to have been, paved the way for Harry Wright's professionalization of baseball. The Athletics were very successful, but Pike was dropped from the team in 1867, because he was from New York, and thus a 'foreigner,' calling his loyalty into question.

He moved on to the Irvington, New Jersey club and later in 1867 to the New York Mutuals, always a leading team, where he returned for 1868, having caught the eye of Boss Tweed. In 1869 he moved to the Brooklyn Atlantics, another perennial leader, where he hit .610. In 1870, the Atlantics, with Pike manning second base, finally ended Cincinnati's 93-game winning streak.

In 1871, the National Association was formed as the first professional baseball league, and Pike joined the Troy Haymakers for its inaugural season. He was their star and for 4 games was the "captain" (which meant that he managed the team), batting .377 (6th best in the league) and hitting a league-leading 4 home runs. He also led the league in extra base hits (21), and was 2nd in slugging percentage (.654) and doubles (10), 4th in RBIs (39), 5th in triples (7), 6th in on base percentage (.400), 9th in hits (49), and 10th in runs (43). The Haymakers only finished 6th, though, and the team's captaincy switched to Bill Craver.

The Haymakers revamped their roster for the 1872 season, and Pike headed for Baltimore, where he played for the Baltimore Canaries. Pike had another excellent season, leading the league in home runs again (with 6), RBIs (60), and games (56), and coming in 2nd in total bases (127) and extra base hits (26), 3rd in at bats (288), 5th in doubles (15) and triples (5), 9th in slugging percentage (.441) and stolen bases (8), and 10th in hits (84).

In 1873 Pike led the league in home runs for the 3rd consecutive season, hitting 4, and was 2nd in triples (8), 4th in total bases (132), stolen bases (8), and extra base hits (26), 7th in slugging percentage (.462), 8th in doubles (14), RBIs (50), and at bats (286), 9th in hits (90), and 10th in games (56).

Baltimore went bankrupt after the season, so Pike headed off to captain the Hartford Dark Blues for the 1874 season. The Dark Blues were a poor team, but Pike had another fine season, slugging .574 to lead the league, and coming in 2nd with an on base percentage of .368.

Pike abandoned the weak Hartford team after a single season, switching to the St. Louis Brown Stockings. For the first time in his professional career, Pike failed to hit a home run, although he stole 25 bases. He also hit 12 triples and 22 doubles (leading the league) in what was probably his finest offensive season.

In all Lip Pike has the NA career home run (15), and extra base hits (135) records

In 1876, when the National League replaced the National Association, Pike stuck with St. Louis. The Brown Stockings turned in a very good season, finishing a solid 2nd to the Chicago White Stockings. Pike continued to produce offensively, notching totals of 133 total bases (5th in the league) and 34 extra-base hits (2nd).

Seemingly never content to stay with a team very long, Pike headed to the Cincinnati Reds for the 1877 season. The Reds finished last. He hit a powerful and famous home run that year, which apparently went 360 far and 40 feet high, and hit a metal bar at that point which it still had enough force to bend. Pike was still a top-quality player, leading the league in home runs for the 4th time in the 1870s. However, age was starting to catch up with the 32-year-old Pike. He began the season as the 8th-oldest player in the league, and was the 4th oldest player of the 1878 season. The 1878 Reds played very well, though. They finished 2nd, but Pike was replaced by Buttercup Dickerson halfway through the season and forced to look elsewhere for a team. He ended up playing a few games for the Providence Grays, and spent the next 2 years playing for minor league teams.

Pike got a brief call-up in 1881 to play for the Worcester Ruby Legs, but the 36-year-old Pike could no longer play effectively, hitting .111 and not managing a single extra base hit in 18 at-bats over 5 games. His play was so poor as to arouse suspicions, and Pike found himself banned from the National League that September. He was added to the "blacklist" at a 1881 National League meeting, barring him from playing for or against any NL team. He turned to haberdashery, the vocation of his father, and spent another 6 years playing only amateur baseball. He was reinstated in 1883.

In 1887, the New York Metropolitans of the American Association gave Pike another chance. At 42, he was the oldest player in baseball. The only game he played was more of a sending off than a new start, though, and Pike headed back to his haberdashery once more.

In 1936, decades after he died, he received a vote in the elections for the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Pike was also one of the fastest players in the league. He would occasionally race any challenger for a cash prize, routinely coming out the winner. On August 16, 1873, he raced a fast trotting horse named "Clarence" in a 100-yard sprint at Baltimore's Newington Park, and won by four yards with a time of 10 seconds flat, earning $250 ($4,570 in current dollar terms).

Pike died suddenly of heart disease at the age of 48 in 1893. The Brooklyn Eagle reported that "Many wealthy Hebrews and men high in political and old time baseball circles attended the funeral service". He was interred in the Salem Fields Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York.

He was the first famous Jewish baseball player, and was inducted into the International Jewish Sports Hall of Fame.

The First Great Jewish Ballplayer: Lipman Pike

Was born in the Fourth Ward

from Jewish Heroes and Heroines in America, from Colonial Times to 1900:

from Jewish Heroes and Heroines in America, from Colonial Times to 1900:

"Lip" Pike: Baseball's First Pro

by Seymour "Sy" Brody

Lipman E. "Lip" Pike became baseball's first professional player when the Philadelphia Athletics recognized his talent in 1866. The team gave him $20 a week to play third base. Pike was soon followed by others. The baseball players of the time were professional and amateurs.

Pike was born in New York City on May 26, 1845. He was one of five children of Jane and Emanuel Pike, emigres from Holland. His older brother, Boaz, was the first in the family to play baseball on an organized team. The first time that Pike's name appeared in a box score was a week after his bar mitzvah. He had played for the Nationals at first base and his brother had played shortstop. The two brothers played for many teams from 1864 through 1865.

Pike established himself as a home run hitter for the year that he was with Philadelphia Athletics as a professional. Hitting home runs was a rarity in those days. Pike hit them in clusters. He hit six home runs in a game against the Alerts in 1886. Five were hit in a row.

Pike left the Athletics and became the playing manager of the Irvington team in 1867. However, he didn't finish the season with the team. Boss Tweed of New York City made him an offer to play for the Mutuals and he accepted it.

He stayed with the Mutes for one year and left the team to join the Brooklyn Atlantics. The Cincinnati Red Stockings came East and beat every team they played, including the Atlantics, in 1869. The following year, the team returned to Brooklyn and was undefeated in 130 games. They played the Atlantics in a game that went into extra innings. The Atlantics took the lead 8 to 7. Pike played second base and was the key figure in retiring the Reds for Atlantics victory.

The first baseball league composed of only professional players began in 1871. Pike went to Troy, New York, to become the manager of the team there. During this period, teams quickly came into being and then quickly disappeared. There wasn't a reserve clause. Many players were drifters, drunkards, and gamblers. Pike was an exception. Pike moved to Baltimore for the 1872-73 season and played in the outfield. He was a very fast runner. It is told that Pike won $200 when he defeated a horse in a race.

Pike played and managed many teams after his stay in Baltimore. He moved around the East Coast, going from one team to another. He finished the year with the Worcester, Massachusetts, team in 1881. The team had a bad season and Pike was made the scapegoat. Pike was the first to be put on baseball's blacklist.

He opened up a haberdashery store and announced his retirement from baseball. The store was a gathering place for baseball enthusiasts. Pike made an attempt to play again when he was 42 years old. He joined the original New York Mets, later announcing his retirement.

Pike became an umpire in the National League and the American Association while still operating his haberdashery. He died of a heart attack at the age of 48. "He was eulogized in many newspapers." the Sporting News said. "He was one of the baseball players in those days, who was always gentlemanly on and off the field - a species which is becoming rarer as the game grows older..." Pike will always be remembered as the first professional player in baseball.

This is one of the 150 illustrated true stories of American heroism included in Jewish Heroes and Heroines of America, © 1996, written by Seymour "Sy" Brody of Delray Beach, Florida, illustrated by Art Seiden of Woodmere, New York, and published by Lifetime Books, Inc., Hollywood, FL.

Friday, April 29, 2011

Wednesday At The Tenement Museum

One of KV's greatest punchball players, of any ethnicity , Prof. Bob Nathanson, joined me at the Tenement Museum to hear Mark Kurlansky talk about his biography of Hank Greenberg called Hank Greenberg: The Hero Who Didn't Want to Be One.

The talk was excellent, due in great part to Kevin Baker's expert facilitation, but I was somewhat disappointed in the book. Ira Berkow's bio is much better.

but I did pick up a clue from the Kurlansky book to the Greenberg's lower east side roots. David Greenberg, Hank's dad, had a job as a clothes sponger and with a little census detective work I figured out he lived at 210 E. 3rd Street in 1906. The document image in the inset is part of Greenberg's naturalization application.

about clothes' sponging

The talk was excellent, due in great part to Kevin Baker's expert facilitation, but I was somewhat disappointed in the book. Ira Berkow's bio is much better.

but I did pick up a clue from the Kurlansky book to the Greenberg's lower east side roots. David Greenberg, Hank's dad, had a job as a clothes sponger and with a little census detective work I figured out he lived at 210 E. 3rd Street in 1906. The document image in the inset is part of Greenberg's naturalization application.

about clothes' sponging

Basically, this is going be entirely dependent on how thorough the shrinkage process at the mill was. Top quality mills usually pre-shrink cloth better. However, any cotton fabric may still shrink to varying degrees. Some tailors who are particularly meticulous won't trust what cloth merchants say about their cloths being "pre-shrunk" and even "sponge" the cloth to shrink it before making it up. For those interested this is traditionally done with bed sheets that have been soaked in water. However, one tailor told me that he wets the cloth and places it in a dryer.a previous post about Hank Greenberg

Saturday, May 1, 2010

Cardboard Gods 2

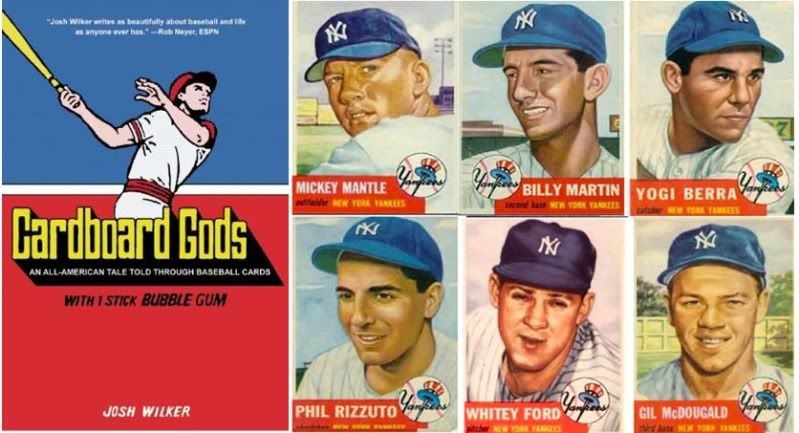

I put together a podcast of an episode of only a game with scans of early 1950 baseball cards.

Yes, my mom threw away my baseball cards. I forgive her.

Cardboard Gods

An excerpt from a review of a new book about baseball cards

Through Baseball Cards, a Meditation on LifeThe book is available here

By GREG HANLON

Josh Wilker, in his Web site, Cardboardgods.net, has garnered a cult following from his lyrical autobiographical musings inspired by his 1970s-era baseball card collection.

The format of the blog is simple: For each entry, Wilker posts a scanned image of a card taken from the shoebox, usually picturing a bushy-haired, mustachioed “God” in a polyester double-knit uniform. The card works as a jumping-off point to tell pieces of his life story. Those pieces are synthesized in his memoir, “Cardboard Gods: An All-American Tale Told Through Baseball Cards,” which hit bookstores on Monday.

The book is part coming-of-age tale, part love letter to baseball in the 1970s and to the decade in general, and part attempt to come to terms with the author’s unconventional upbringing to which his lifelong attachment to his cards seems largely traceable. It follows the same format as his blog, with each chapter loosely centering on a late ‘70s baseball card pasted onto the page.

For instance, Wilker uses the card of Herb Washington -– a former sprinter with no discernible baseball skills whom the Oakland A’s signed for the sole function of pinch running -– as a portal into a meditation on the decade’s celebration of experimentation. This is a meaningful theme for Wilker because his upbringing represented an experiment of sorts. For much of his early childhood, he and his brother lived in a three-parent home with his father, his mother and his mother’s boyfriend. Later, his mother and boyfriend moved the family to Vermont to “live off the land,” sending the long-haired boys to a school with no grade levels or structured curriculum.

“Look, it was time to Try New Things,” Wilker writes in the Washington chapter. “Not all of those things worked. But even in the mistakes, or maybe especially in the mistakes, the cockeyed grandeur of the 1970s comes through.”

Amid the confusion surrounding the era in general and their upbringing in particular, Wilker and his brother turned to baseball and baseball cards. The cardboard gods were tangible connections to a mythical American normalcy and clarity missing in their lives.

Thursday, March 18, 2010

Guadalcanal Diary

with the Pacific being shown on HBO. I thought I'd post this:

It was part of my History First Hand resources from 2002 www.gothamcenter.org/k12/history1hand/HistoryFirstHand/course2_4.html

Boy is William Bendix missed. He was a Yankee fan even before he played Babe Ruth. Here's an article the Daily News did many years ago on "New York Characters" that goes with this clip:

Taxi Potts, By ELLIOT ROSENBERG

It's Game Two of the 1942 World Series, Sportsman's Park, St.Louis. Cardinal rookie Stan Musial awaits New York hurler Ernie Bonham'spitch, bottom of the eighth, as Enos Slaughter, the winning run, inches off second. Musial s-w-i-n-g-s, the sputtering radio set carrying play-by-play action snaps and crackles — and the game's highlight is erased. You can't blame

Aloysius T.Potts for growling in frustration. Or maybe you can. Flatbush-bred Potts, a full-blooded Brooklynite, loudly trumpets his Dodger faith, and Dem Bums didn't even make this World Series. Their 1941 American League conquerors did, and here he is, actually rooting for those damn Yankees. Baseball loyalties should be made of sterner stuff.But you gotta make allowances. Taxi Potts is no longer steering his cab through friendly Prospect Park, Bensonhurst and Coney Island while exulting in the fortunes of Pee Wee Reese, Pete Reiser and Dixie Walker on the car radio. Sure, 12 months back, Mickey Owens' passed ball, which turned the tide in the Yankees' favor, broke his heart. But that was then, this is now, and the wounded radio set around which Cpl.Potts and his Marine platoon mates huddle rests beneath soaring palm trees on steamy, malarial, Japanese-infested Guadalcanal. Any link to the annual rite of nine guys in flannels facing nine other guys in flannels for the world championship thousands of miles away is a link worth grasping. But rooting for the men in Yankee pinstripes? "New York's my home town," Cpl. Potts explains to his new Marine buddies, all out-of-towners from the twangy Midwest or drawling South. Anyway, he amplifies his excuse: "Who ever said anything about Flatbush being part of New York? It's vice versa." Pinpointing on a map Guadalcanal, strategic jewel of the Solomons chain, would have left Potts geographically challenged. But as he crossed the ocean to fight for Kings County and country, he had much more to learn (check treetops for snipers, wear your helmet, beware of booby-trapped souvenirs). And some things to unlearn. Selection of small arms, for example. Aboard the transport conveying them, conventional troops prepare ammunition belts, but Taxi shows off his private arsenal. "That's not government-issue," a sergeant points out. "No, that's Flatbush-issue," responds the unapologetic Taxi, confidently waving his blackjack. "Do you want to take the island all by yourself?" "That would go over good in Brooklyn!" Cocky before combat, Taxi Potts is a bearlike, earthy, dems-and-dese guy, whether joshing a teenage recruit about his first stubble of facial hair ("You know your mother don't let you go with no dames") or ruminating on his own dealings with the opposite sex ("That's a tomato, every time").

He longs for the simple pleasures of bygone days — his beverage of choice, for example. There'd be Mom, pouring "a swig of gin. What a sweet old lady." And, of course, "Ebbets Field, that's for me. Just watching my beautiful Bums." But now, there's a war to be won. Initial landings go strangely unopposed. But snipers hidden amid palm leaves soon take their toll, and night infiltrators turn Marine sentries trigger-happy. Behind the beach, American troops take a Japanese landing strip, rename it Henderson Field and prepare perimeter defenses. "Maybe if we dig deep

enough," muses Taxi, "we'll come out somewhere near Ebbets Field." Counterattacks, bomb runs by Japanese planes farther up the Solomons chain and nightly shellings by warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy make life a nightmare for nearly 11,000 men of the 1st Marine Division. The grueling campaign now under way fosters a durable rhyme about Marines standing before the Pearly Gates and reporting to St. Peter that they've already served their time in hell. And the ordeal extracts from normally lighthearted Potts some somber reflections: "I don't know about those other guys, but this thing is over my head. I ain't much at this praying business. My old lady took care of that. I'm no hero. I'm just a guy. I don't want no medals. I just want to get this thing over with and get back home." "Guadalcanal Diary," the movie, loosely adapted from "Guadalacanal Diary," the book, combat correspondent Richard Tregaskis' day-by-day account, premiered at the Roxy on Nov. 17, 1943. The film's fictional Marine unit contributed to an evolving Hollywood formula — a geographical melting pot with a Texan, a Southerner, a Midwesterner and, unfailingly, a guy from Brooklyn. This one was played by New York-born William Bendix, later radio and television's lovably bumbling Chester W. Riley. According to Borough President John Cashmore's numbers, 327,000 real Brooklynites took part in the war effort, 71,000 of them laboring in round-the-clock shifts at the Navy Yard from which the star battlewagons Iowa and Missouri rolled into the East River. Over in Red Hook, the Todd

Shipyard churned out the workhorse assault landing craft that carried the Taxi Pottses of the 1st Marines to enemy-held atolls throughout the Pacific. And Brooklyn's unglamorous Army Terminal became departure point for 50% of the East Coast's war zone-headed cargo.

"A Long Way From Brooklyn — And Them Beautiful Bums," proclaimed the "Guadalcanal Diary" theater ads about Flatbush's native son. Ironically, even as Potts' lament reached the neighborhoods, Italian POWs shifted here from North Africa were being hospitably interned at Greenpoint, an enviable 5-cent ride from The House That Ebbets Built. Enough to make Taxi grumble, Riley-like: "What a revoltin' development this is! "Personal for Taxi: Still haven't caught up? Here's the Sportsman's Park update for Oct. 1, 1942 (Oct. 2 on Guadalcanal's side of the International Date Line): Musial singles. Slaughter races home. The Cards win.

Sunday, February 14, 2010

Saturday, January 30, 2010

Monday, October 12, 2009

Coleman Oval Pitching Star And Son

Considered by most to be the best pitcher ever in Two Bridges Little League History.

Sorry Murray.

about Vinny Adimando, from Joe Bruno

After little league, where he dominated for three years, Vinny was all-city at LaSalle High School. And a two-time All American at St. John's. Also a member of the United States Nation team for two years. He also played in the Cape Cod League, and made the all-star team twice.

In his first year in Pony League for Transfiguration, Vinnie pitched, played the outfield, and batted third. He was 13 years old. It was my third year in Pony League. I was 15, played shortstop and was the lead off hitter.

During the season, our coach Frank Mosco, told me there was going to be a bunch of scouts at our game to watch Vinnie. He told me he wanted Vinnie to lead off, so he'd get more at bats. I was moved down to the second slot. No problem.

In the first inning, Vinnie was up, and I was standing on deck. We were playing at DeWitt Clinton Field at 53th Street, and 11th ave. in Manhattan.

In the first inning, Vinnie hit the first, or second pitch, a heat-seeking missile over the left centerfield fence, and all the way across 11th Avenue, which was a 2-way street. You could hear the jaws dropping all over the field. I don't think anybody ever saw an 8th grader hit a ball that far.

So I'm up next. There was no way for me to follow that act. In fact, I don't think anyone was actually watching my at bat. Not even the pitcher.

Not even my father.

So I did what I did best. I bunted down the third base line for a base hit.

Nobody noticed. And rightfully so.

Friday, September 18, 2009

Playing Softball In Sara Delano Roosevelt Park 1935

The view is looking NE towards Forsyth Street. PS 91 is seen in the distance on the corner of Stanton Street. The picture comes from the nyc parks collection

Labels:

baseball,

sara delano roosevelt park,

schools,

Ward 10

Monday, September 14, 2009

Thursday, September 10, 2009

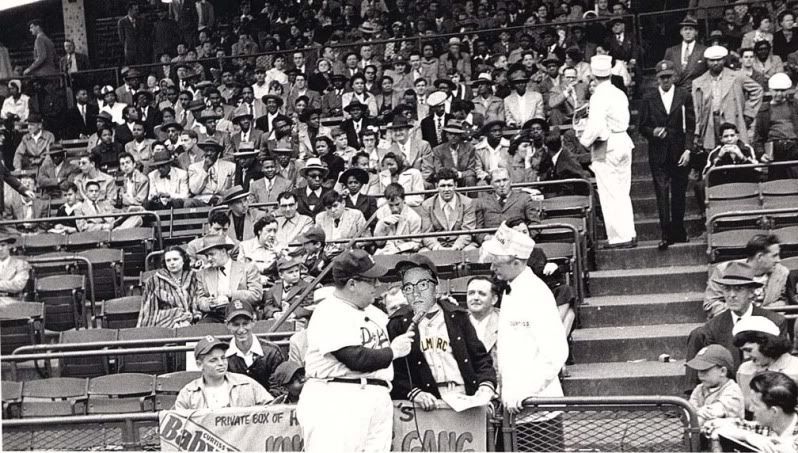

Happy Felton's Knothole Gang

Even the old Dodgers are happy for Derek Jeter.The pictures are mostly from the 1955 or 1956 season. About Happy Felton, Date of Birth, 30 November 1907, Bellevue, Pennsylvania, USA, Date of Death, 21 October 1964 from baseball-fever

Another popular show on WOR Ch. 9 was "Happy Felton's Knothole Gang", a sports show that helped young baseball players improve their baseball playing skills. (This show was not "Joe DiMaggio's Dugout", which was seen Saturday afternoons on WNBT TV Ch. 4 and in national syndication during the early 1950's, where Mr. DiMaggio and the members of his dugout would try to improve the baseball playing techniques by watching top ball players on film.)

Happy Felton (a former vauldville, stage and radio comic actor and musical entertainer) & the members of NYC's most successful little league teams would see professional players ultilize their ball playing techniques live on the fields of the Brooklyn Giants, Brooklyn Dodgers and N.Y. Yankees Stadiums.

After seeing their heroes play on the fields, the kids were given the chance to play against themselves on the fields and earn the chance to win scholarships for their schools and toy prizes. Plus tickets to upcoming baseball games.

"Happy Felton's Knothole Gang" was seen weekday afternoons and on Saturday afternoons on WOR Ch. 9 from Friday, April 21, 1950 until station execs finally closed up Happy Felton's knothole in the ball parks for good on Saturday, August 24, 1957.

...it was a pre game show before Brooklyn Dodger home telecasts and since the Dodgers televised every home gane on channel 9 it was telecast either during afternoons, evening, Sunday's whatever (only before the first game for a Sunday doubleheader.)...There were 3 contestants not 5 as somebody claimed. It was only held at Ebbets Field...as a matter of fact it was telecast from the Dodger bullpen which was in foul territory along the right field line (since it was only 297 to the right field fair pole (as Warner Wolf would say of course it's the fair pole, if the ball hits it, it's a fair ball) just in front of the right field wall. It was telecast up through the last telecast from Ebbets Field the night Danny McDevit shut out the Pirates, the last major league game that was ever to be played in Brooklyn by the true Dodgers...the winner of that last contest is still probably waiting to collect his prize (a visit with his favorite Dodger,some time in the Dodger dugout and then through the clubhouse)....normally the Dodger telecasts began each season with the Friday afternoon exhibition game against the Yankees the Friday before the season began (the Brooks and Yanks then played Saturday and Sunday at Yankee Stadium)....

Labels:

baseball,

benny goodman,

brooklyn dodgers,

happy felton

Tuesday, September 8, 2009

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)