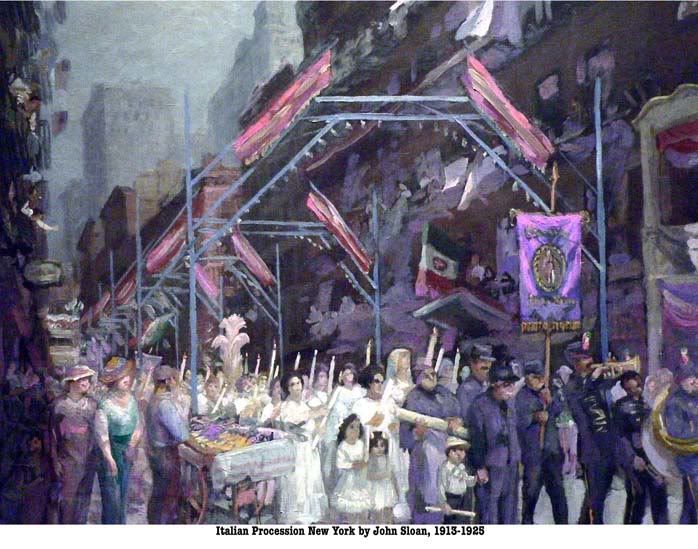

While we're hanging out in Ward's 6 and 14 we should take in an Italian Procession

Ashcan Views of New Yorkers, Warts, High Spirits and All

By KEN JOHNSON December 28, 2007

The painters of the Ashcan School just wanted to have fun. They chronicled the lives of poor city dwellers, but they were neither social critics nor reformers. Robert Henri, George Luks, John Sloan and other early-20th-century American realists identified with the group were high-spirited fellows who prided themselves on fielding a baseball team that regularly defeated those of the National Academy of Design and the Art Students League. They liked to dine in fancy restaurants and hang out at McSorley’s, the men’s-only tavern on East Seventh Street. They enjoyed the theater, the circus and trips to Coney Island. No Puritan crusaders, they were manly epicureans, and their virile hero was Teddy Roosevelt.

Such is the view propounded by “Life’s Pleasures: The Ashcan Artists’ Brush With Leisure” at the New-York Historical Society. Organized by James W. Tottis, associate curator of American art at the Detroit Institute of Arts, the exhibition presents more than 80 paintings by 22 artists dating from 1895 to 1925 that focus on scenes of recreation: bars and restaurants, sporting events, carnivals, parks and beaches.

The exhibition will not prompt any great re-evaluation of the Ashcan School. Its painters were not of world-class spiritual depth or formal imagination. But they were a lively bunch of provincial rebels who created America’s first true avant-garde, and their chapter in the book of art history is still fascinating.

The show also commemorates the forthcoming centenary of the exhibition that put the Ashcan School on the map: the 1908 show at MacBeth Gallery in New York called “The Eight,” which included Henri, Luks and Sloan, as well as William Glackens, Arthur B. Davies, Ernest Lawson, Maurice Prendergast and Everett Shinn. Henri organized the show to protest the rejection of himself and his friends from the National Academy of Design’s spring exhibition the previous year.

It was not until much later, however, that the Ashcan School got its name. In 1916 a staff member of the socialist magazine The Masses objected to the insufficiently high-minded “pictures of ashcans and girls hitching up their skirts on Horatio Street” by Sloan, George Bellows and others of the Henri circle that illustrated the magazine.

Elevated or not, the Ashcan painters were drawn to what they saw as the vitality of the lower classes. Bellows’s 1907 painting “Forty-two Kids,” in which a gang of mostly naked boys swims off a decaying Hudson River pier, is not an indictment of poverty but an anti-academic celebration of unsupervised freedom, spontaneity and play.

Favoring a brushy, gestural application inspired by the paintings of Hals, Velázquez and Manet, the Ashcan artists were action painters who mirrored the flux of reality with the flux of their brushwork, and, sometimes, by intensifying light and color. See, for example, Shinn’s extraordinarily luminous paintings of theatrical productions.

Many of the Ashcan painters were well prepared for this approach, having started out as newspaper illustrators. Being able to draw on the run, however, did not necessarily translate into very good painting. Ashcan paintings often look muddy and too hastily made.

Judging by an exhibition of his etchings at the Museum of the City of New York, Sloan, for one, was a better draftsman than painter. Most of the 34 prints in “John Sloan’s New York” are not much bigger than postcards, but teeming as they are with affectionate, finely detailed observations of old, young, poor and rich on sidewalks, in parks and on subways, they have a Dickensian amplitude.

This being America at the turn of the 20th century, sexuality tends to be muted, but it’s not totally repressed. One of Sloan’s most delightful prints shows a young woman descending subway stairs: Her skirt has flipped up in a sudden gust, giving a man going up the stairs a leggy eyeful. And back at the Ashcan show, there’s Henri’s bigger-than-life painting of a voluptuous model posing as a smirking Salome in a sparkly halter top, with bared midriff and sheer fabric revealing her naked legs; it was shocking enough in 1910 to be rejected from the National Academy’s spring annual.

Glackens’s sumptuous, Impressionist-style masterpiece, “Chez Mouquin,” intimates a socio-sexual complexity that is mostly missing from the rest of the show. The image of a beautiful, extravagantly dressed, sad-eyed young woman sitting in a restaurant with a beefy, prosperous-looking man in a tuxedo is like a scene from Edith Wharton’s “House of Mirth,” which, as it happens, was published in 1905, the same year as the painting was made. Alternatively, Guy Pène du Bois’s haunting, smoothly simplified, slyly satiric pictures of upper-class people in empty rooms could illustrate novels by Henry James.

In 1913 disaster struck the Ashcan School in the form of the Armory Show, which, by introducing European avant-gardists like Picasso, Matisse and Duchamp to America, caused the near-total eclipse of native realism.

If Ashcan painting looks like a dead end today, we should not forget that it gave birth to two indisputably great American painters: Edward Hopper and Stuart Davis. It might also be said that the Ashcan spirit returned in Abstract Expressionism, a movement that favored visceral action over aesthetic refinement. Willem de Kooning’s famous line — “I always seem to be wrapped in the melodrama of vulgarity” — could have been the Ashcan motto.

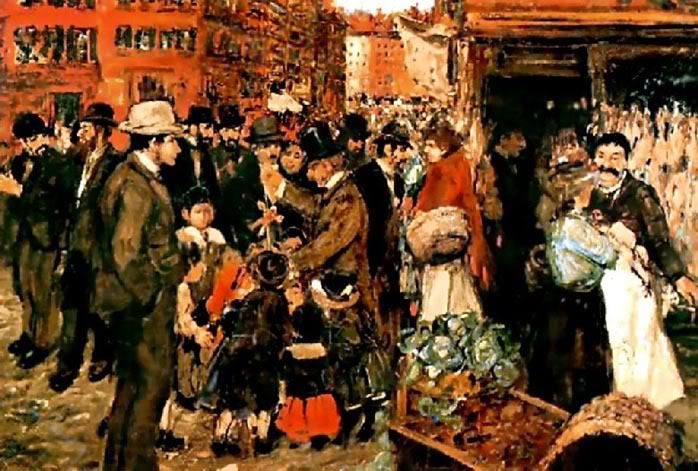

Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, William Glackens, 1870-1938, became a part of the Realist painters following Robert Henri, but much of his work avoids the seamier side of society and shows bustling middle class activity. He also adopted Impressionism and did many paintings of seaside resorts on Cape Cod and Long Island, particularly Bellport where he and his family spent summers.

He graduated from Philadelphia's Central High School with John Sloan and in 1891 became an artist-reporter for the 'Philadelphia Record.' He did the same kind of work from 1892 to 1895 for the 'Philadelphia Press' with John Sloan, George Luks, and Everett Shinn. He studied briefly at the Pennsylvania Academy with Thomas Anshutz and then shared a studio and traveled in Europe with Robert Henri. There he painted many scenes of life in He settled in New York, worked as an illustrator, and was part of 'The Eight,' a landmark exhibition of urban realists at the Macbeth Galleries. Early in his painting career, he painted numerous scenes of Washington Square and Central Park but then turned to beach scenes.

Long ago and far away, I dreamed a dream one day

And now that dream is here beside me

Long the skies were overcast but now the clouds have passed

You're here at last

Chills run up and down my spine, Aladdin's lamp is mine

The dream I dreamed was not denied me

Just one look and then I knew

That all I longed for long ago was you

Chills run up and down my spine, Aladdin's lamp is mine

The dream I dreamed was not denied me

Just one look and then I knew

That all I longed for long ago was you

John French Sloan (August 2, 1871 - September 8, 1951) was a U.S. artist. He was born in Lock Haven, Pennsylvania., to a businessman father and a schoolteacher mother. At the age of 20, he became an illustrator with The Philadelphia Inquirer. He studied art in the evening at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, where he met his mentor, Robert Henri, author of "The Art Spirit." Sloan's style was heavily influenced by European artists of the late 19th and early 20th century. He was familiar with Van Gogh's work, as well as Picasso, and Matisse, and several of his works appear as if they are a fusion of European styles.

Sloan moved to Greenwich Village in New York, where he painted some of his best-known works, including McSorley's Bar, Sixth Avenue Elevated at Third Street and Wake of the Ferry. In later years, he spent summers working and painting in Gloucester, Massachusetts, and Santa Fe, New Mexico.

He was allied with the Ashcan School and a member of The Eight, a group of American realist artists that included Robert Henri, Everett Shinn, Arthur B. Davies, Ernest Lawson, Maurice Prendergast, George Luks, and William J. Glackens. One of his students was Norman Raeben.

“The fun of being a New York painter, says Sloan, even today, is that landmarks are torn down so rapidly that your canvases become historical records almost before the paint on them is dry.” Esquire, 1936

When John and Dolly Sloan arrived in New York in 1904, they were two of approximately 100,000 people moving to the city that year. The Sloans settled in Chelsea, one of the city’s commercial centers, where shops, moving picture parlors, and entertainment halls of every sort clustered around Sixth Avenue. Sloan’s apartment at 165 West 23rd Street (between Sixth and Seventh Avenues) bordered on the Tenderloin, a district famous for its nightclubs and bordellos. His living room window looked out on what he termed “the busy throng on 23rd Street.” This throng and their activities—walking to the theaters, window shopping and, above all else, watching each other—would become the subject of Sloan’s prints and paintings. The landmarks in Sloan’s early New York paintings are the elevated train tracks, streets, shops, and dive bars of his neighborhood, rather than the city’s tourist sites.

Sloan’s student, Guy Pène du Bois, described him eloquently as “the historian of Sixth Avenue, Fourteenth Street, Union Square, Madison Square.”

Madison Square Park, located just a few blocks from his home, was one of Sloan’s favorite sites during his years in Chelsea. In Sloan’s New York, the parks, like the streets, were places where diverse individuals encountered each other every day. The city allowed male and female, old and young, affluent and impoverished, to observe and comment on each other, a pleasure which Sloan indulged in his art.

In 1912 Sloan moved first his studio and then his apartment down Sixth Avenue to Greenwich Village. In moving to the Village, Sloan left a commercial center in Chelsea for the heart of the city’s liberal, intellectual community, subtly shifting his alliance from the workaday world of Chelsea and the Tenderloin to the city’s most bohemian and artistic quarter. The Village was fast becoming a haven for creative types, and in the popular imagination, it represented a place outside the bounds of middle-class social norms. Emblematic of this was the neighborhood’s physical fabric, much noted in Sloan’s day. With its meandering streets, where 4th Street crosses 10th Street, Greenwich Village was literally outside the grid of New York City, a characteristic celebrated by its creative residents. The anarchist Hippolyte Havel stated that the Village had no geographical boundaries; it was “a spiritual zone of mind.” Filled with artists, writers, and political radicals, Greenwich Village appeared to exist apart from the bustling capitalist center that was Manhattan.

Sloan found a community in the Village, and many of his paintings and etchings document that community’s leaders—Romany Marie Marchand, Juliana Force, Hippolyte Havel, Eugene O’Neill—and landmarks—Jefferson Market, Washington Square, McSorley’s Bar, the Lafayette, and the Golden Swan.

Sloan remained in the Village for more than two decades, becoming, by the 1920s, one of the neighborhood’s artistic features, mentioned in guidebooks. He stayed to see the Village overrun by tourists and, in the 1920s, by speakeasies known as “tea rooms.” He saw Seventh Avenue extended and the subway run through the Village, and in 1927 the Sloans were forced to vacate their apartment on Washington Place because it was being demolished as part of subway construction and the extension of Sixth Avenue southward. They settled on Washington Square South, and Sloan’s relocation inspired a spate of photographs of Sixth Avenue, the Square and of One Fifth Avenue, an art deco skyscraper under construction just above the north end of the park. A tower of luxury apartments, One Fifth Avenue was a sign of gentrification to come. When New York University took over the building housing Sloan’s apartment on Washington Square in 1935, the Sloans were unable to find affordable accommodations in the Village. They returned to Chelsea. For the rest of his life, Sloan kept an apartment in the Chelsea Hotel, only blocks from his first home in New York City.

Reginald Marsh (14 March 1898 - 3 July 1954) was an American painter, born in Paris, most notable for his detailed depictions of life in New York City in the 1920s and 1930s. He produced many watercolors, egg tempera paintings, oil paintings, Chinese ink drawings, and a number of lithographs and etchings.

Reginald Marsh was born in an apartment in Paris above the Café du Dome. Although he was most famous for his sketches and paintings, he also produced series' of photographs and linoleum cuts. He was the second son born to his parents who were both artists themselves. His mother, Alice Randall was a miniaturist painter and his father Fred Dana Marsh was one of the earliest American painters to depict modern industry. When Marsh was two years old his family moved to Nutley, New Jersey. He was able to attend prestigious schools in the states because his grandfather was a very well known man.

Marsh attended the Lawrenceville School and graduated in 1920 from Yale University. At Yale Art School he worked as the star illustrator for the Yale Record, the college newspaper. Marsh was noted to have fully enjoyed his time at Yale because he received a typical college experience. Marsh also secured full time jobs after graduation, he worked as a freelance illustrator, for the New York Daily News and for the The New Yorker. He also submitted illustrations to the New Masses, (a published American Marxist journal from the 1920s to the 1940s.)

Marsh did not really enjoy painting until the 1920s, when he began to study with other artists. By 1923 Marsh began to take painting more seriously. During his trip to Paris, he was able to see famous paintings at the Louvre and other museums, which fueled his excitement to paint. It was the first time Marsh had visited Paris since he had lived there as a child and he fell in love with what it had to offer him. Marsh was impressed by the 'old master' paintings he saw on a 1926 European trip. He returned with a desire to utilize the principles he felt were evident in the art of the Renaissance painters, particularly the practice of taking notes from observation of human subjects in their environments. Marsh then studied under Kenneth Hayes Miller, John Sloan and George Luks at the Art Students League of New York, and chose to do fewer commercial assignments.

Marsh had been influenced by the drawings of Raphael, Leonardo Da Vinci and Michelangelo since he was a child. When Marsh returned to New York City in the late 1920s after meeting Benton and learning from the "masters," he began to study with Kenneth Hayes Miller. Miller was a well known painter at the time and was teaching at the Art Students League of New York. Miller instructed Marsh on the basics of form and design in his art. He encouraged Marsh to make himself known to the world. He looked at Marsh's early, awkward burlesque sketches and at his more conventional landscape watercolors and said, "These awkward things are your work. These are real. Stick to these things and don’t let anyone dissuade you!" By the beginning of the 1930s Marsh began to express himself fully in his art. As late as 1944 Marsh wrote, “I still show him every picture I paint. I am a Miller student."

Reginald Marsh’s style can best be described as social realism. His style emerged as one that strives to capture the human figure in the context of reality. Marsh’s work depicted the Great Depression. What was expressed in his work was the effort to move out of the Great Depression. Therefore, his paintings have a social message for the need of a change. Although the need for change didn't occur, and he was not successful in ending the terrible conditions he saw because the nation was in bits and pieces, Marsh’s work was successful. His portraits depict a range of social classes that were heavily divided because of the economic crash. Marsh’s caricatures were people who had a crisis thrust upon them; which is why his work shows a loss of human integrity and control in all aspects.Marsh developed a love of crowds, of movement, form, and pattern, but at the same time he also depicted figures alone; showing the division of social classes. Marsh’s main attractions were the burlesque stage, the hobos on the Bowery, crowds on city streets and at Coney Island, and women.Marsh's etchings were his first work as an artist. In the early 1920s he began to work with watercolor and oil. He did not take to oil naturally and decided to stick to watercolor for the next decade. Yet, in 1929 he discovered egg tempera, which he found to be somewhat like watercolor but with more depth and body. Along with Marsh's paintings, he was also highly noted for his print's, first working in etching and lithography, and then moving on to ancient engravings in the 1940s. He kept careful watch of the technique he used for his prints. He noted the temperature of the room, the age of the bath that his plates were soaked in, the composition, and the length of time the plate was etched.

In Marsh’s earlier years, the 1920s, he drew from burlesque theatrical acts. At this time vaudeville and burlesque acts were flourishing throughout the country and were available all over New York City. The burlesque that Marsh captured can be described as raunchy and vulgar, but also comedic, and satiric. Marsh’s drawings depict chorus girls, clowns, theater goers and even strippers. Burlesque was "the theater of the common man; it expressed the humor, and fantasies of the poor, the old, and the ill-favored."Marsh felt alive when painting the burlesque and discovered that he himself was an entertainer.

Drawing people on the sidewalks and on street corners connected Marsh to the harsh reality of the life on the Bowery. Marsh simply believed that the lower class was more interesting to paint although he was not economically part of the lower class. In the 30s the hobo became a familiar figure in America because of the Great Depression that was sweeping the country.Marsh also painted other figures, such as the burlesque queens, the musclemen, and bathing beauties all of whom personified the 1930s for him. In 1930 Marsh was 32 years old living in New York, yet not starving as much of the country was because he had inherited his grandfathers money, besides having his own career.

Marsh liked to venture out to Coney Island to paint, especially in the summer time. There he began to paint massed beached bodies.[When Marsh looked at the contemporary world it reminded him of the world of the old masters. Marsh’s deep devotion to the old masters, led to his creating works of art in a style that reflects certain artistic traditions. His work often contained religious metaphors. Marsh’s crowd paintings are reminiscent of the Last Judgment, because of the masses of bodies tangled and weaved among each other. He also emphasizes the bold muscles and build of his characters, which relate to the heroic scale of the older European paintings. Marsh said "I like to go to Coney Island because of the sea, the open air, and the crowds - crowds of people in all directions, in all positions, without clothing, moving - like the great compositions of Michelangelo and Rubens." Through the techniques he had learned and connecting those techniques to what he saw, Marsh was able to capture characters of the present day and introduce them to the old masters whom he wished he knew from the past.

Marsh was also drawn to the ports of New York. He would sketch the seaports, focusing on the tugboats coming in and out of the harbor. He loved to include the details of the boats such as the masts, the bells, the sirens, and the deck chairs to capture the true reality of the vessels. In the 1930s the harbors were extremely busy with people and commerce due to the country’s necessity for economic recovery.The Great Depression brought about a decline in raw materials and therefore the demand for those materials grew dramatically. This caused the chaotic need for trade along with bustling harbors, in big cities such as New York.

Like on Coney Island and in the seaports of New York, Marsh captured the crowds of the bustling inner city life. Marsh spent a lot of his time on the sidewalks, the subways, the nightclubs, bars and restaurants finding the crowds. He also loved to single people out on the trains, in the parks, or in ballrooms to capture a single human figure and distinguish them from the rest of the city.

Marsh was also obsessed with the American woman as a sexual and powerful figure. This obsession began with his involvement in movie scenes and burlesque theaters. In his work with movies he made sure to capture all different sides to the theater, the rich and the poor and the women as revelers and powerful.In the 1930s during the Great Depression more than 2 million women lost their jobs and during this time was when women were said to be exploited sexually. Marsh’s work shows this exploitation by portraying men and women in the same paintings. Because Marsh was a painter of bodies his paintings depicted women as half clothed, or fully naked, often big and strong. The men portrayed in Marsh’s paintings were portrayed as voyeurs, often watching the women. These paintings share a relationship with the old masters, by portraying the raw sexuality of women. They were often erotic, and populated with heroic-like images.

The painting Fourteenth Street at the Museum of Modern Art depicts Marsh's interest in women. It illustrates a large crowd in front of a theater hall, showing the clashing of classes and of gender in the 1930’s. It features a large community of people interacting but at the same time, it singles certain people out, showing the socio-economic disruption of society and class. The women in the painting are depicted as strong and purposeful with large bodies. Women are idealized in this work and they appear larger then the men. They appear untouchable and unattainable. While the women look active and powerful, the men look like drunk hobos and are portrayed much smaller. The woman walking under the ladder is a large looming strong figure, while the man beneath her walks by on crutches and is slumped over.[Marsh’s world is filled with display: movies, burlesque, the beach, and all forms of public exhibition. Men and women are both spectators and performers within a heavily sexualized world. And Marsh was clearly fascinated by both aspects of that world - almost always presenting its two sides in the same image.” During the 1940s and for many years Reginald Marsh became an important teacher at the Art Students League of New York.

Although Marsh died in 1954, his artwork lives on in many places today. He is believed to be one of the greatest artists of all time by some of his close friends, Edward Laning, and Norman Sasowsky. Many of his prints and thousands of unpublished sketches were found in his estate after he died. They revealed more of the true depth of his work.

From smithsonianmag.si.edu: "A fire rages on 24th Street, bright lights illuminate a Broadway stage, pushcart peddlers market their wares, a horse bolts across a steaming street. These scenes from everyday life in New York City at the turn of the century were produced by a group of artists who came to the booming city to create art rooted in the "real life" of their time. From 1897 to 1917, in paintings and graphic works of power and wit, artists George Bellows, William Glackens, Robert Henri, George Luks, Everett Shinn and John Sloan framed a contemporary realism that explored the drama, humor and exoticism of life in the turbulent metropolis. Their distinctive vision captured the energy of the city's streets and squares, and chronicled the dynamic social changes taking place as cobblestones and churches gave way to subways and skyscrapers. From horse-drawn wagons to motorized trolleys, from Fifth Avenue mansions to the teeming tenements of the Lower East Side, they caught the pulse of a city in transition." I used posterized John Sloan images with Ms. Rosen's class last year when they were doing period studies with a visiting educator from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Here's a sampling of Sloan's work

from 9/2005 from pseudo-intellectualism with a slide show attached at the end

from 9/2005 from pseudo-intellectualism with a slide show attached at the end This feels like an association game. Greenwich Village could be New York's favorite neighborhood for architecture and history and a major source for "home." It comes backed by a wealth of resources. It was a favorite backdrop for the ashcan artists, (John Sloan,above, for one), for writers and for film. The Age of Innocence gives us a great view of period interiors. Barry Lewis and David Hartman have partnered in the wonderful "A Walk Through Series." Here are the titles and info on their availability: A Walk Across 42nd Street, A Walk Up Broadway, A Walk Around Harlem, A Walk Around Brooklyn, A Walk in Greenwich Village, A Walk Through Central Park, A Walk Through Newark, A Walk Through Hoboken, A Walk Through Queens. The Channel Thirteen Hartman/Lewis series of videos listed are available individually, for about $20 each + tax + shipping, by contacting 800.336.1917 (Thirteen's video ordering department). You might have to ask the 800 operator to scroll down the entire video list because the Hartman/Lewis videos are quixotically listed under different titles. DVD versions of Broadway, Harlem, Brooklyn, Greenwich Village and Central Park should be out by December, 2005. Here's a clip from the Greenwich Village video in which Lewis discusses "back tenements." Here's a second portion of that clip.