Personalize funny videos and birthday eCards at JibJab!

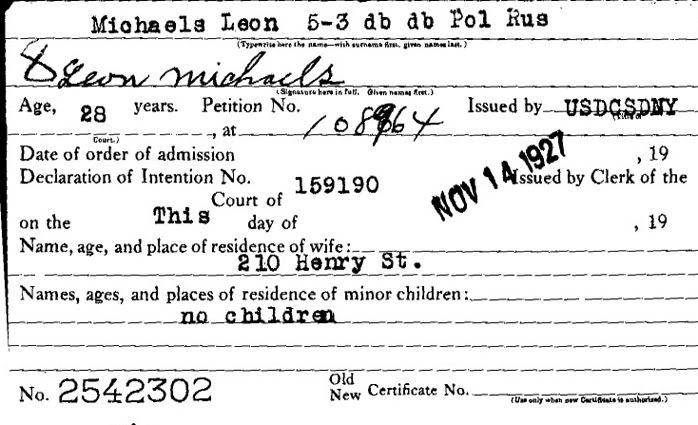

Probably from the The 1956 Winter Olympics, officially known as the VII Olympic Winter Games, in Cortina d'Ampezzo, Italy. It's Leonard Michaels and Mario Fox

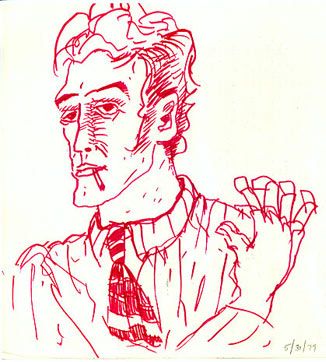

to the left a self portrait of Leonard Michaels In the recently released book of essays there's a story that mentions two Knickerbocker Village neighbors of Leonard Michaels, Lynn Nations and Arthur Kleinman. Leonard lived in the L Building, 20 Monroe Street. An excerpt from My Yiddish

to the left a self portrait of Leonard Michaels In the recently released book of essays there's a story that mentions two Knickerbocker Village neighbors of Leonard Michaels, Lynn Nations and Arthur Kleinman. Leonard lived in the L Building, 20 Monroe Street. An excerpt from My YiddishWhen I was five years old, I started school in a huge gloomy Vic-torian building where nobody spoke Yiddish. It was across the street from Knickerbocker Village, the project in which I lived. To cross that street meant going from love to hell. I said nothing in the classroom and sat apart and alone, and tried to avoid the teacher’s evil eye. Eventually, she decided that I was a moron, and wrote a letter to my parents saying I would be transferred to the "ungraded class" where I would be happier and could play ping-pong all day. My mother couldn’t read the letter so she showed it to our neighbor, a woman from Texas named Lynn Nations. A real American, she boasted of Indian blood, though she was blond and had the cheekbones, figure, and fragility of a fashion model. She would ask us to look at the insides of her teeth, and see how they were cupped. To Lynn this proved descent from original Americans. She was very fond of me, though we had no conversation, and I spent hours in her apartment looking at her art books and eating forbidden foods. I could speak to her husband, Arthur Kleinman, yet another furrier, and a lefty union activist, who knew Yiddish.

Lynn believed I was brighter than a moron and went to the school principal, which my mother would never have dared to do, and demanded an intelligence test for me. Impressed by her Katharine Hepburn looks, the principal arranged for a school psychologist to test me. Afterwards, I was advanced to a grade beyond my age with several other kids, among them a boy named Bonfiglio and a girl named Estervez. I remember their names because we were seated according to our IQ scores. Behind Bonfiglio and Estervez was me, a kid who couldn’t even ask permission to go the bathroom. In the higher grade I had to read and write and speak English. It happened virtually overnight so I must have known more than I knew. When I asked my mother about this she said, “Sure you knew English. You learned from trucks.” She meant: while lying in my sickbed I would look out the window at trucks passing in the street; studying the words written on their sides, I taught myself English. Unfortunately, high fevers burned away most of my brain, so I now find it impossible to learn a language from trucks. A child learns any language at incredible speed. Again, in a metaphorical sense, Yiddish is the language of children wandering for a thousand years in a nightmare, assimilating languages to no avail.

I remember the black shining print of my first textbook, and my fearful uncertainty as the meanings came with all their exotic Englishness and de-voured what had previously inhered in my Yiddish. Something remained indigestible. What it is can be suggested, in a Yiddish style, by contrast with English. A line from a poem by Wallace Stevens, which I have discussed elsewhere, seems to me quintessentially goyish, or antithetical to Yiddish:

Actually, they did not have any children, that's why they kind of adopted all of us kids. Their apartment was next door to ours. Since Arthur was Jewish he could speak to my parents in Yiddish which bridged the gap. Lynn was incredible, a real presence.

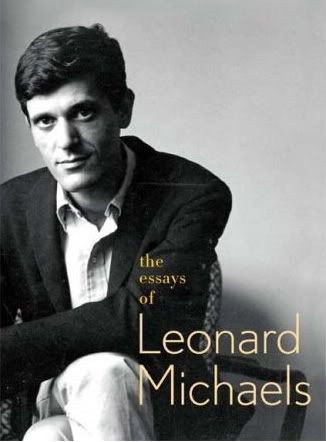

available from amazon and at the Washington Post's Book World Reviewed by Jonathan Yardley :

available from amazon and at the Washington Post's Book World Reviewed by Jonathan Yardley : Leonard Michaels was a sublimely gifted prose stylist who died much too soon, in 2003 -- he had barely reached his 70th birthday but suffered from lymphoma -- and who left a slender but durable literary legacy. Primarily a writer of short stories, he made an improbable appearance on the bestseller lists in 1981 with his novel "The Men's Club," perhaps because it appeared at precisely the moment when its portrayal of male bonding coincided with feminist ridicule of male rituals. Such fame as that brought him was pretty much dashed five years later when the book was transformed into a dreadful movie, leaving Michaels feeling, as he says in one of the essays in this collection, "like a rape victim who not only suffers the opinions of cops but also feels guilty." That wry, self-mocking comment is typical of Michaels the writer, as it was of Michaels the man. At almost exactly the time that "The Men's Club" was published, I came to know him slightly -- he was teaching at Johns Hopkins, and I was living in Baltimore -- and to like him a great deal. In 1984 I served as chairman of the fiction jury for the newly revived National Book Awards and, hoping to have a jury whose members would have literary tastes diametrically opposed to my own, asked Michaels and Laurie Colwin to serve with me. No one was more surprised than I when we agreed, immediately and unanimously, to give the award to the unknown Ellen Gilchrist for her second book of stories, "Victory over Japan." To the best of my recollection, I never spoke or wrote to Michaels thereafter, but I remembered him with pleasure and was shocked by his death, just as I had been by Colwin's even more sudden and premature death in 1992. So I have been delighted to see his publisher bringing out his work in new editions over the past three years, first "The Collected Stories of Leonard Michaels" (2007) and now his collected essays. This is a considerably leaner book than the collected stories, but it packs a lot of punch and is filled, as was all his work, with sentences that border on poetry. If it is true that, as years ago someone said, Gore Vidal (as essayist) writes in perfectly shaped paragraphs, it is equally true that Leonard Michaels writes in perfectly shaped sentences. This would be cause for admiration and celebration in any writer, but surely it is far more so for one who did not begin to speak English until he was 5 years old. His parents immigrated from Poland to Manhattan's Lower East Side only steps ahead of the Holocaust -- "When the Nazis seized Brest Litovsk, my grandfather, grandmother, and their youngest daughter, my mother's sister, were buried in a pit with others" -- and in their tiny apartment the language spoken was Yiddish. That, and Jewishness, permeate his writing, as no one knew more keenly than he did: "Eventually I learned to speak English, then to imitate thinking as it transpires among English speakers. To some extent, my intuitions and my expression of thoughts remain basically Yiddish. . . . This moment, writing in English, I wonder about the Yiddish undercurrent. If I listen, I can almost hear it: 'This moment' -- a stress followed by two neutral syllables -- introduces a thought that hangs like a herring in the weary droop of 'writing in English,' and then comes the announcement, 'I wonder about the Yiddish undercurrent.' The sentence ends in a shrug. Maybe I hear the Yiddish undercurrent, maybe I don't. The sentence could have been written by anyone who knows English, but it probably would not have been written by a well-bred Gentile. It has too much drama, and might even be disturbing, like music in a restaurant or elevator. The sentence obliges you to abide in its staggered flow, as if what I meant were inextricable from my feelings and required a lyrical note. There is a kind of enforced intimacy with the reader. A Jewish kind, I suppose. In Sean O'Casey's lovelier prose you hear an Irish kind." Michaels said his literary influences included Franz Kafka, Lord Byron and Wallace Stevens (this last is frequently quoted in these essays), but reading that paragraph one can't help thinking that as a young man in the 1950s he must have spent a lot of time listening to Mort Sahl, Lenny Bruce and the other great Jewish comedians of the day, as his own comic voice and timing bear more than passing resemblance to theirs. In another essay, "A Sentimental Memoir," he recalls being "saved" as a young man by a professor of English at the University of Michigan named Austin Warren, and then he meanders into an account of falling "insanely in love" (which seems to have been a strong predilection with him) with a girl in Warren's class: "The girl had a slender boyish figure and blondish hair. I thought nobody but me considered her striking or had noticed the subtle perfection of her beautiful face. When I told my friend Julian that the most beautiful girl in Michigan was in Warren's class, he named her. He told me that she modeled naked for art students, she had a horrible reputation for licentiousness, everybody knew who she was, and that he was in love with her too. I decided that I was ready to forgive her everything. To forgive a girl was a very popular sentiment of the day. There were plays, novels, and movies about forgiving bad girls. As for the girl I was ready to forgive, I now suppose there were a couple of hundred other men who were forgiving her at the same time, all of us subject to a sort of spiritual narcissism that has long since gone out of the world. Too bad, I think, since it had extraordinary intensity and made a man feel tortured by goodness, which is a very high order of feeling." The phrasing ("tortured by goodness") and timing of that paragraph are absolutely perfect, and it points to a recurrent theme in these essays, not merely the autobiographical ones but also the critical ones about books, art and movies. Michaels certainly was no sentimentalist, but he strongly preferred the more modest, introspective, feeling culture of his youth to the arrogant, assertive, rude one of the present. Writing about the paintings of Edward Hopper, he gets to the point: "We rap, we shriek in the raving crowd, and wear clothing big enough to hold two or three people, and walk about wearing earphones, or talking into cell phones, lest we feel alone. There are no philosophers. In Hopper's day we wore tight clothing and held each other close, saying nothing, dancing slowly, shuffling a few inches this way and that, feeling possessed, possessed by feeling. People preferred feeling to sex." And, a few pages later: "There used to be obscenity. There used to be a distinction, as between day and night, between private and public. There used to be privacy." These are not the maunderings of one seized by nostalgia, but ones of an acutely sensitive man who was appalled by the coarsening of what now passes for adult civilization. As it happens this is a horror that I feel myself, which doubtless predisposes me to these essays, but what really matters is that you'll look for a long time to find writing as good as this and thinking as clear.

from thisrecording from his second collection of short stories, I Would Have Saved Them If I Could.

from thisrecording from his second collection of short stories, I Would Have Saved Them If I Could.In the fifties I learned to drive a car. I was frequently in love. I had more friends than now. When Khrushchev denounced Stalin my roommate shit blood, turned yellow, and lost most of his hair. I attended the lectures of the excellent E.B. Burgum until Senator McCarthy ended his tenure. I imagined N.Y.U. would burn. Miserable students, drifting in the halls, looked at one another.

In less than a month, working day and night, I wrote a bad novel.

I went to school—N.Y.U., Michigan, Berkeley—much of the time.

I had witty, giddy conversation, four or five nights a week, in a homosexual bar in Ann Arbor.

I read literary reviews the way people suck candy.

Personal relationships were more important to me than anything else.

I had a fight with a powerful fat man who fell on my face and was immovable.

I had personal relationships with football players, Jazz musicians, ass-bandits, nymphomaniacs, non-specialized degenerates, and numerous Jewish premedical students.

I had personal relationships with thirty-five rhesus monkeys in an experiment on monkey addiction to morphine. Thy knew me as one who shot reeking crap out of cages with a hose.

With four other students I lived in the home of chiropractor named Leo.

I met a man in Detroit who owned a submachine gun; he claimed to have hit Dutch Schultz. I saw a gangster movie that disproved his claim.

I knew two girls who had brains, talent, health, good looks, plenty to eat, and hanged themselves.

I heard of parties in Ann Arbor where everyone made it with everyone else, including the cat.

I knew card sharks and con men. I liked marginal types because they seemed original and aristocratic, living for an ideal or obliged to live in it. Ordinary types seem fundamentally unserious. These distinctions belong to the romantic fop. I didn't think that way too much.

I worked for an evil vanity publisher in Manhattan.

I worked in a fish packing plant in Massachusetts, on the line with a sincere Jewish poet from Harvard and three lesbians; one was beautiful, one grim; both loved the other, who was intelligent. I loved her, too. I dreamed of violating her purity. They taked among themselves, in creepy whispers, always about Jung. In a dark corner, away from our line, old Portuguese men slit fish into open flaps, flicking out the bones. I could only see their eyes and knives. I'd arrive early every morning to dash in and out until the stench became bearable. After work I'd go to bed and pluck fish scales out of my skin.

I was a teaching assistant in two English departments. I graded thousands of freshman themes. One began like, "Karl Marx, for that was his name…" Another began like this: "In Jonathan Swift's famous letter to the Pope…" I wrote edifying comments in the margins. Later I began to scribble "Awkward" beside everything, even spelling errors.

I got A's and F's as a graduate student. A professor of English said my attitude wasn't professional. He said that he always read a "good book" after dinner.

A girl from Indiana said this of me on a teacher-evaluation form: "It is bad enough to go to English class at eight in the morning, but to be instructed by a shabby man is horrible."

I made enemies on the East Coast, the West Coast, and in the Middle West. All now dead, sick, or out of luck.

I was arrested, photographed, and fingerprinted. In a soundproof room two detectives lectured me on the American way of life, and I was charged with the crime of nothing. A New York cop told me that detectives were called "defectives."

I had an automobile accident. I did the mambo. I had urethritis and mononucleosis.

In Ann Arbor, a few years before the advent of Malcolm X, a lot of my friends were black. After Malcolm X, almost all my friends were white. They admired John F. Kennedy.

In the fifties, I smoked marijuana, hash, and opium. Once I drank absinthe. Once I swallowed twenty glycerine caps of peyote. The social effects of "drugs," unless sexual, always seemed tedious. But I liked people who inclined the drug way. Especially if they didn't proselytize. I listened to long conversations about the phenomenological weirdness of familiar reality and the great spiritual questions this entailed—for example, "Do you think Wallace Stevens is a head?"

I witnessed an abortion.

I was godless, but I thought the fashion of intellectual religiosity more despicable. I wished that I could live in a culture rather than study life among the cultured.

I drove a Chevy Bel Air eighty-five miles per hour on a two-lane blacktop. It was nighttime. Intermittent thick white fog made the headlights feeble and diffuse. Four others in the car sat with the strict silent rectitude of catatonics. If one of them didn't admit to being frightened, we were dead. A Cadillac, doing a hundred miles per hour, passed us and was obliterated in the fog. I slowed down.

I drank Old Fashioneds in the apartment of my friend Julian. We talked about Worringer and Spengler. We gossiped about friends. Then we left to meet our dates. There was more drinking. We all climbed trees, crawled in the street, and went to a church. Julian walked into an elm, smashed his glasses, vomited on a lawn, and returned home to memorize Anglo-Saxon grammatical forms. I ended on my knees, vomiting into a toilet bowl, repeatedly flushing the water to hide my noises. Later I phoned New York so that I could listen to the voices of my parents, their Yiddish, their English, their logics.

I knew a professor of English who wrote impassioned sonnets in honor of Henry Ford.

I played freshman varsity basketball at N.Y.U. and received a dollar an hour for practice sessions and double that for games. It was called "meal money." I played badly, too psychological, too worried about not studying, too short. If pushed or elbowed during a practice game, I was ready to kill. The coach liked my attitude. In his day, he said, practice ended when there was blood on the boards. I ran back and forth, in urgent sneakers, through my freshman year. Near the end I came down with pleurisy, quit basketball, started smoking more.

I took classes in comparative anatomy and chemistry. I took classes in old English, Middle English, and modern literature. I took classes and classes.

I fired a twelve-gauge shotgun down the hallway of a railroad flat into a couch pillow.

My roommate bought the shotgun because of his gambling debts. He expected murderous thugs to come for him. I'd wake in the middle of the night listening for a knock, a cough, a footstep, wondering how to identify myself as not him when they broke through out door.

My roommate was an expensively dressed kid from a Chicago suburb. Though very intelligent, he suffered in school. He suffered with girls though he was handsome and witty. He suffered with boys though he was heterosexual. He slept on three mattresses and used a sun lamp all winter. He bathed, oiled and perfumed his body daily. He wanted soft, sweet joys in every part, but when some whore asked if he'd like to be beaten with a garrison belt, he said yes. He suffered with food, eating from morning to night, loading his pockets with fried pumpkin seeds when he left for class, smearing caviar paste on his filet mignons, eating himself into a monumental face of eating because he was eating. Then he killed himself.

A lot of young, gifted people I knew in the fifties killed themselves. Only a few of them continue walking around.

I wrote literary essays in the turgid, tumescent manner of darkest Blackmur.

I used to think that someday I would write a fictional version of my stupid life in the fifties.

I was a waiter at a Catskill hotel. The captain of the waiters ordered us to dance with the female guests who appeared in the casino without escorts and, as much as possible, fuck them. A professional tummler walked the ground. Whenever he saw a group of people merely chatting, he thrust in quickly and created a tumult.

I heard the Budapest String quartet, Dylan Thomas, Lester Young, and Billie Holiday together, and I saw Pearl Primus dance, in a Village nightclub, in a space two yards square, accompanied by an African drummer about seventy years old. His hands moved in spasms of mathematical complexity at invisible speed. People left their tables to press close to Primus and see the expression in her face, the sweat, the muscles, the way her naked feet seized and released the floor.

Eventually I had friends in New York, Ann Arbor, Chicago, Berkeley & Los Angeles.

I did the cha-cha, wearing a tux, at a New Year's party in Hollywood, and sat at a table with Steve McQueen. He'd become famous in a TV series about a cowboy with a rifle. He said he didn't know which he liked best, acting or driving a racing car. I thought he was a silly person and then realized he thought I was. I met a few other famous people who said something. One night, in a yellow Porsche, I circle Manhattan with Jack Kerouac. He recited passages, perfectly remembered from his book reviews, to the sky. His manner was ironical, sweet, and depressing.

I had a friend named Chicky who drove his chopped, blocked, stripped, dual-exhaust Ford convertible, while vomiting out the fly window, into a telephone pole. He survived, lit a match to see if the engine was all right, and it blew up in his face. I saw him in the hospital. Through his bandages he said that ever since high school he'd been trying to kill himself. Because his girlfriend wasn't good-looking enough. He was crying and laughing while he pleaded with me to believe that he had really been trying to kill himself because his girlfriend wasn't good-looking enough. I told him that I was going out with a certain girl and he told me that had fucked her once but it didn't matter because I could take her away and live somewhere else. He was a Sicilian kid with a face like Caravaggio's angels of debauch. He'd been educated by priests and nuns. When his hair grew back and his face healed, his mind healed. He broke up with his girlfriend. he wasn't nearly as narcissistic as other men I knew in the fifties.

I knew one who, before picking up his dates, ironed his dollar bills and powdered his testicles. And another who referred to women as "cockless wonders" and used only their family names—for example, "I'm going to meet Goldberg, the cockless wonder." Many women thought he was extremely attractive and became his sexual slaves. Men didn't like him.

I had a friend who was dragged down a courthouse stairway, in San Francisco, by her hair. She'd wanted to attend the House Un-American hearings. The next morning I crossed the Bay Bridge to join my first protest demonstration. I felt frightened and embarrassed. I was bitter about what had happened to her and the others she'd been with. I expected to see thirty or forty people lke me, carrying hysterical placards around the courthouse until the cops bludgeoned us into the pavement. About two thousand people were there. I marched beside a little kid who had a bag of marbles to throw under the hoofs of the horse cops. His mother kept saying, "Not yet, not yet." We marched all day. That was the end of the fifties.

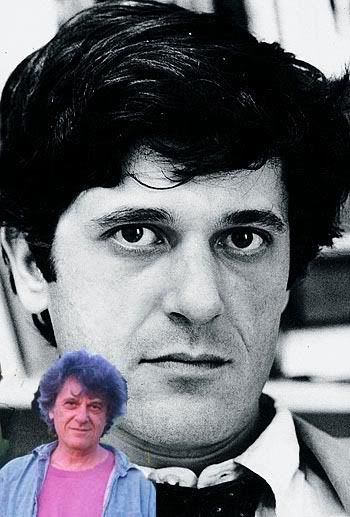

Leonard Michaels died in 2003. He was one of the most talented writers of the short story in the form's history. He also wrote novels, including The Men's Club, a brilliant satire, and Sylvia, about his first wife, Sylvia Bloch.

Leonard Michaels, arguably KV's greatest

Leonard Michaels, arguably KV's greatestNovelist, short story writer, critic, and professor, Leonard Michaels was born to Polish immigrants and raised on New York’s Lower East Side. Like contemporaries Philip Roth and Woody Allen, he wrote brilliant stories about young, sex-crazed, bookish New Yorkers until his death in 2003. Though not as known to the public as Roth or Allen, he was praised as an original by his fellow writers. Below is an extended excerpt from LEONARD MICHAELS: The Collected Stories by Leonard Michaels.

“Murderers” (I think all KVers will recognize the setting. I think I know a KVer who Philip reminds me of)

When my uncle Moe dropped dead of a heart attack I became expert in the subway system. With a nickel I’d get to Queens, twist and zoom to Coney Island, twist again toward the George Washington Bridge—beyond which was darkness. I wanted proximity to darkness, strangeness. Who doesn’t? The poor in spirit, the ignorant and frightened. My family came from Poland, then never went anyplace until they had heart attacks. The consummation of years in one neighborhood: a black Cadillac, corpse inside. We should have buried Uncle Moe where he shuffled away his life, in the kitchen or toilet, under the linoleum, near the coffeepot. Anyhow, they were dropping on Henry Street and Cherry Street. Blue lips. The previous winter it was cousin Charlie, forty-five years old. Moe, Charlie, Sam, Adele—family meant a punch in the chest, fire in the arm. I didn’t want to wait for it. I went to Harlem, the Polo Grounds, Far Rockaway, thousands of miles on nickels, mainly underground. Tenements watched me go, day after day, fingering nickels. One afternoon I stopped to grind my heel against the curb. Melvin and Arnold Bloom appeared, then Harold Cohen. Melvin said, “You step in dog shit?” Grinding was my answer. Harold Cohen said, “The rabbi is home. I saw him on Market Street. He was walking fast.” Oily Arnold, eleven years old, began to urge: “Let’s go up to our roof.” The decision waited for me. I considered the roof, the view of industrial Brooklyn, the Battery, ships in the river, bridges, towers, and the rabbi’s apartment. “All right,” I said. We didn’t giggle or look to one another for moral signals. We were running.

The blinds were up and curtains pulled, giving sunlight, wind, birds to the rabbi’s apartment—a magnificent metropolitan view. The rabbi and his wife never took it, but in the light and air of summer afternoons, in the eye of gull and pigeon, they were joyous. A bearded young man, and his young pink wife, sacramentally bald. Beard and Baldy, with everything to see, looked at each other. From a water tank on the opposite roof, higher than their windows, we looked at them. In psychoanalysis this is “The Primal Scene.” To achieve the primal scene we crossed a ledge six inches wide. A half-inch indentation in the brick gave us fingerholds. We dragged bellies and groins against the brick face to a steel ladder. It went up the side of the building, bolted into brick, and up the side of the water tank to a slanted tin roof which caught the afternoon sun. We sat on that roof like angels, shot through with light, derealized in brilliance. Our sneakers sucked hot slanted metal. Palms and fingers pressed to bone on nailheads.

The Brooklyn Navy Yard with destroyers and aircraft carriers, the Statue of Liberty putting the sky to the torch, the dull remote skyscrapers of Wall Street, and the Empire State Building were among the wonders we dominated. Our view of the holy man and his wife, on their living-room couch and floor, on the bed in their bedroom, could not be improved. Unless we got closer. But fifty feet across the air was right. We heard their phonograph and watched them dancing. We couldn’t hear the gratifications or see pimples. We smelled nothing. We didn’t want to touch.

For a while I watched them. Then I gazed beyond into shimmering nullity, gray, blue, and green murmuring over rooftops and towers. I had watched them before. I could tantalize myself with this brief ocular perversion, the general cleansing nihil of a view. This was the beginning of philosophy. I indulged in ambiance, in space like eons. So what if my uncle Moe was dead? I was philosophical and luxurious. I didn’t even have to look at the rabbi and his wife. After all, how many times had we dissolved stickball games when the rabbi came home? How many times had we risked shameful discovery, scrambling up the ladder, exposed to their windows—if they looked. We risked life itself to achieve this eminence. I looked at the rabbi and his wife.

Today she was a blonde. Bald didn’t mean no wigs. She had ten wigs, ten colors, fifty styles. She looked different, the same, and very good. A human theme in which nothing begat anything and was gorgeous. To me she was the world’s lesson. Aryan yellow slipped through pins about her ears. An olive complexion mediated yellow hair and Arabic black eyes. Could one care what she really looked like? What was really? The minute you wondered, she looked like something else, in another wig, another style. Without the wigs she was a baldy-bean lady. Today she was a blonde. Not blonde. A blonde. The phonograph blared and her deep loops flowed Tommy Dorsey, Benny Goodman, and then the thing itself, Choo-Choo Lopez. Rumba! One, two-three. One, two-three. The rabbi stepped away to delight in blond imagination. Twirling and individual, he stepped away snapping fingers, going high and light on his toes. A short bearded man, balls afling, cock shuddering like a springboard. Rumba! One, two-three. Olé! Vaya, Choo-choo!

I was on my way to spend some time in Cuba.

Stopped off at Miami Beach, la-la.

Oh, what a rumba they teach, la-la.

Way down in Miami Beach,

Oh, what a chroombah they teach, la-la.

Way-down-in-Miami-Beach.

She, on the other hand, was somewhat reserved. A shift in one lush hip was total rumba. He was Mr. Life. She was dancing. He was a naked man. She was what she was in the garment of her soft, essential self. He was snapping, clapping, hopping to the beat. The beat lived in her visible music, her lovely self. Except for the wig. Also a watchband that desecrated her wrist. But it gave her a bit of the whorish. She never took it off.

Harold Cohen began a cocktail-mixer motion, masturbating with two fists. Seeing him at such hard futile work, braced only by sneakers, was terrifying. But I grinned. Out of terror, I twisted an encouraging face. Melvin Bloom kept one hand on the tin. The other knuckled the rumba numbers into the back of my head. Nodding like a defective, little Arnold Bloom chewed his lip and squealed as the rabbi and his wife smacked together. The rabbi clapped her buttocks, fingers buried in the cleft. They stood only on his legs. His back arched, knees bent, thighs thick with thrust, up, up, up. Her legs wrapped his hips, ankles crossed, hooked for constriction. “Oi, oi, oi,” she cried, wig flashing left, right, tossing the Brooklyn Navy Yard, the Statue of Liberty, and the Empire State Building to hell. Arnold squealed oi, squealing rubber. His sneaker heels stabbed tin to stop his slide. Melvin said, “Idiot.” Arnold’s ring hooked a nailhead and the ring and ring finger remained. The hand, the arm, the rest of him, were gone.

We rumbled down the ladder. “Oi, oi, oi,” she yelled. In a freak of ecstasy her eyes had rolled and caught us. The rabbi drilled to her quick and she had us. “OI, OI,” she yelled above congas going clop, doom-doom, clop, doom-doom on the way to Cuba. The rabbi flew to the window, a red mouth opening in his beard: “Murderers.” He couldn’t know what he said. Melvin Bloom was crying. My fingers were tearing, bleeding into brick. Harold Cohen, like an adding machine, gibbered the name of God. We moved down the ledge quickly as we dared. Bongos went tocka-ti-tocka, tocka-ti-tocka. The rabbi screamed, “MELVIN BLOOM, PHILLIP LIEBOWITZ, HAROLD COHEN, MELVIN BLOOM,” as if our names, screamed this way, naming us where we hung, smashed us into brick.

Nothing was discussed.

The rabbi used his connections, arrangements were made. We were sent to a camp in New Jersey. We hiked and played volleyball. One day, apropos of nothing, Melvin came to me and said little Arnold had been made of gold and he, Melvin, of shit. I appreciated the sentiment, but to my mind they were both made of shit. Harold Cohen never again spoke to either of us. The counselors in the camp were World War II veterans, introspective men. Some carried shrapnel in their bodies. One had a metal plate in his head. Whatever you said to them they seemed to be thinking of something else, even when they answered. But step out of line and a plastic lanyard whistled burning notice across your ass.

At night, lying in the bunkhouse, I listened to owls. I’d never before heard that sound, the sound of darkness, blooming, opening inside you like a mouth.

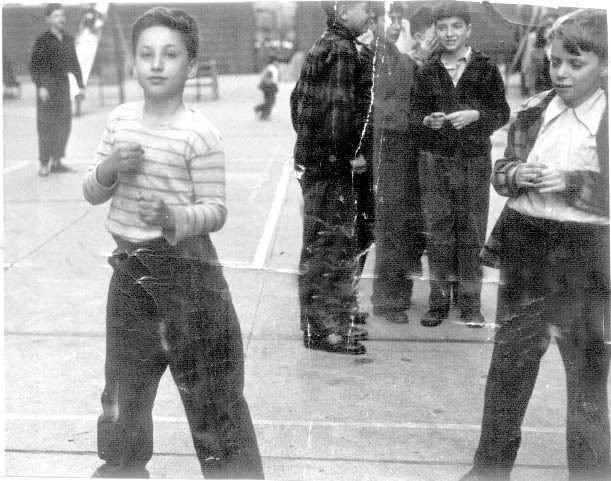

On the right is my brother Sam Boodman. The guy to his right I believe is David Michaels, Lenny Michaels' younger brother. The guy in the middle looking at David could be Lenny or a Paul Seligson. Lenny and David had a sister named Carol. They lived in the apartment underneath mine on the 2nd floor at 20 Monroe

Michaels' essay on watching Gilda has similar moments — he says that seeing the “zipper business” made more of an impression on him than WW II — and is similarly precise about the location of his film-viewing moment. “I saw this movie in the Loew's Theater on Canal Street in the Lower East Side of Manhattan.” After his libinal viewing experience, he says, “I went down Madison Street, passing under the Manhattan Bridge, then turning left on Market Street, walking toward the East River, until I came to Monroe Street, and turned right.” The person writing-remembering this New York street-walking so meticulously is aged 60 or so, across the continent, on the other coast, in California, but the point is clear, and kind of Hemingway-esque. The hard clarity of street names, recited, might undo the terrible moral lesson the film had conveyed: “The creep touched her. I understood that real life is this way. Nothing would be the same for me again.” I first encountered Leonard Michaels' essay on Gilda in the selection of Best American Essays 1992 edited by Susan Sontag. But when I noticed that it had appeared in the Berkeley-based broadsheet cultural journal, The Threepenny Review, it figured. In the early 1990s, while wandering around bookshops in Berkeley, I picked up some copies of The Threepenny Review (though not the issue with Michaels' essay in it) and have kept up with it on and off ever since. (It's partially available on the Net). The Threepenny Review publishes terrific pieces by people I've always enjoyed reading elsewhere — John Berger, Stephen Greenblatt, Luc Sante, Carol Clover, Carlo Ginzburg — and includes poetry, a film section, essays on photography. Hence, it's always a pleasurable and informative reading experience.

I was thrilled when I stumbled upon the information that a favorite author of mine, Leonard Michaels lived in Knickerbocker Village.

I was thrilled when I stumbled upon the information that a favorite author of mine, Leonard Michaels lived in Knickerbocker Village.Leonard Michaels (January 2, 1933- May 10, 2003) was an American writer of short stories, novels, and essays. He was born in New York City and earned a B.A. from New York University and a M.A. as well as a Ph.D. in English Literature from the University of Michigan, before spending most of his adult life in Berkeley, California. Going Places, his first book of short stories, made his reputation as one of the most brilliant of that era's fiction writers; the stories are urban, funny, and written in a private, hectic diction that gives them a remarkable edge. The follow-up, coming six years later (Michaels was perhaps not prolific enough to build a widely popular career), was I Would Have Saved Them If I Could, a collection as strong as the first. The Men's Club, Michaels' first novel, is a story-like, relatively short comedic work that simultaneously attacks and celebrates the absurdities of men as they gather in a kind of urban support group. In 1986, the novel was made into a popular film, directed by Peter Medak, with the screenplay by Michaels, and starring Roy Scheider, Harvey Keitel, Stockard Channing and Frank Langella. Sylvia is a fictionalized memoir of Michael's first wife, Sylvia Bloch, who committed suicide. Michaels was a professor of English at the University of California, Berkeley. His son Jesse Michaels was vocalist in the seminal underground punk rock band Operation Ivy, a precursor to Rancid.

When I was five years old, I started school in a huge gloomy Vic-torian building where nobody spoke Yiddish. It was across the street from Knickerbocker Village, the project in which I lived. To cross that street meant going from love to hell. I said nothing in the classroom and sat apart and alone, and tried to avoid the teacher’s evil eye. Eventually, she decided that I was a moron, and wrote a letter to my parents saying I would be transferred to the "ungraded class" where I would be happier and could play ping-pong all day. My mother couldn’t read the letter so she showed it to our neighbor, a woman from Texas named Lynn Nations. A real American, she boasted of Indian blood, though she was blond and had the cheekbones, figure, and fragility of a fashion model. She would ask us to look at the insides of her teeth, and see how they were cupped. To Lynn this proved descent from original Americans. She was very fond of me, though we had no conversation, and I spent hours in her apartment looking at her art books and eating forbidden foods. I could speak to her husband, Arthur Kleinman, yet another furrier, and a lefty union activist, who knew Yiddish.

Lynn believed I was brighter than a moron and went to the school principal, which my mother would never have dared to do, and demanded an intelligence test for me. Impressed by her Katharine Hepburn looks, the principal arranged for a school psychologist to test me. Afterwards, I was advanced to a grade beyond my age with several other kids, among them a boy named Bonfiglio and a girl named Estervez. I remember their names because we were seated according to our IQ scores. Behind Bonfiglio and Estervez was me, a kid who couldn’t even ask permission to go the bathroom. In the higher grade I had to read and write and speak English. It happened virtually overnight so I must have known more than I knew. When I asked my mother about this she said, “Sure you knew English. You learned from trucks.” She meant: while lying in my sickbed I would look out the window at trucks passing in the street; studying the words written on their sides, I taught myself English. Unfortunately, high fevers burned away most of my brain, so I now find it impossible to learn a language from trucks. A child learns any language at incredible speed. Again, in a metaphorical sense, Yiddish is the language of children wandering for a thousand years in a nightmare, assimilating languages to no avail.

I remember the black shining print of my first textbook, and my fearful uncertainty as the meanings came with all their exotic Englishness and de-voured what had previously inhered in my Yiddish. Something remained indigestible.