Friday, May 27, 2011

Saturday, May 21, 2011

Questions Over Location Of Lower Manhattan Republican Club

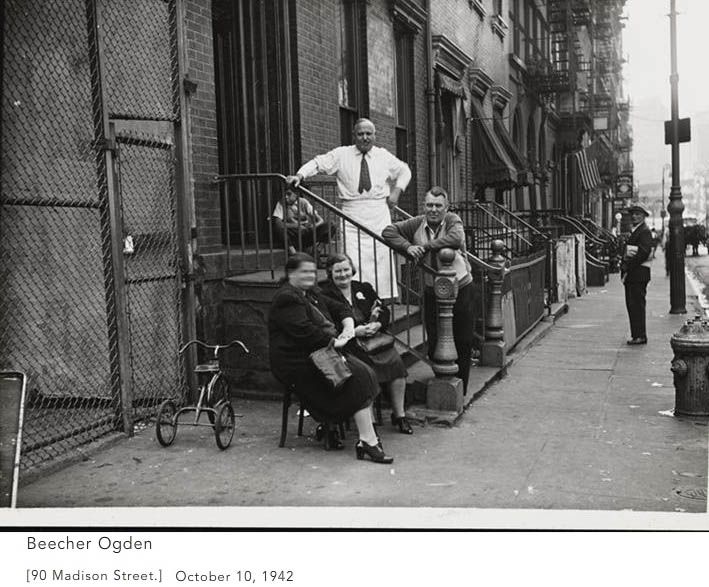

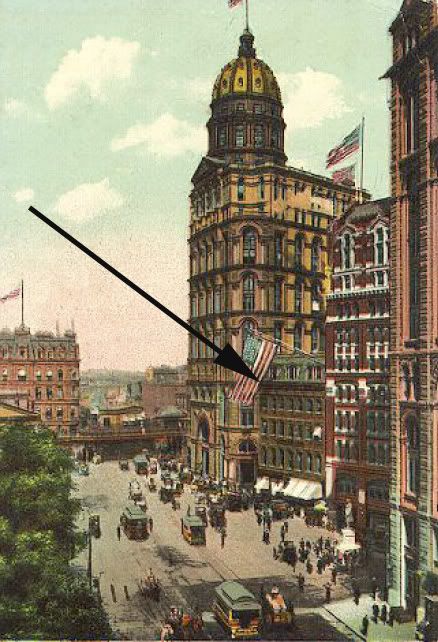

image directly below from the mcny collection

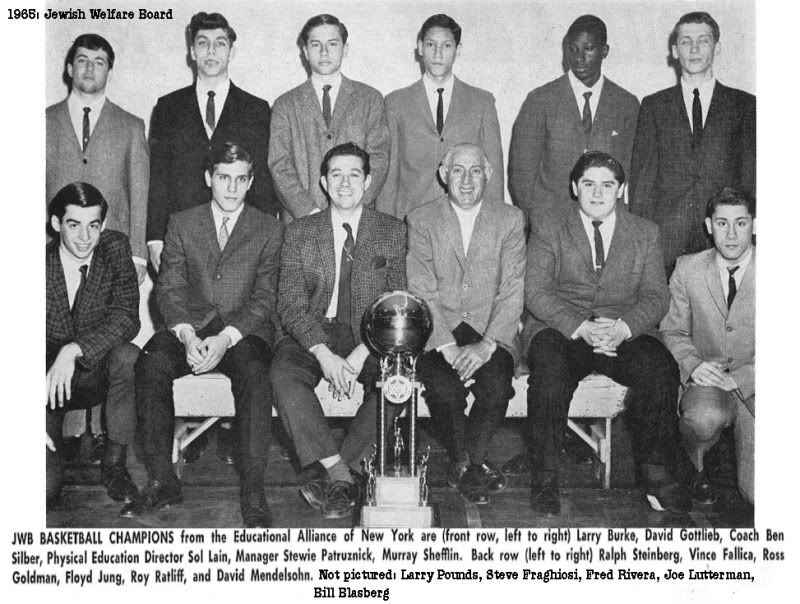

After many of the former LMRC players viewed the lost treasure Weiner film recently posted a comment was made about the location of the Lower Manhattan Republican Club. Howie remarked:

After many of the former LMRC players viewed the lost treasure Weiner film recently posted a comment was made about the location of the Lower Manhattan Republican Club. Howie remarked:

this stuff is awesome - better than the treasure trove from Abbottabad ... who needs a time machine? ... overall look is more like the '50s than 1960 .. great picking out some subtle stuff like that wall that was behind the 3rd base dugout with the cutout leading to the 177 schoolyard ... loved seeing Marty mess with me in the team photo - the price for being a batboy ... btw anyone who might have guessed the address of LMRC was 90 Market - please pick up your prize. Thanks Barry , Dave.I remarked, using the above photos, as proof

I used to think it was on Market too, but that was the democractic club.Murray made a good point, however

90 Market didn't exist at that time. That address was to the right of PS 177 and those buildings were torn down by that date.

lmrc was at 90 Madison

I remember the club being across from the A & P in the space that was the delli.My response:

Marty & I held a New Years eve party their one year

I'm sure you are right. maybe it moved there after leaving madison street. that party probably was after the exodus to warbasse

Tuesday, May 17, 2011

East Broadway And The Garden Cafeteria

The Garden was recognized by place matters

a comment by Carol Foresta, a former KVer

Thanks for the Garden Cafeteria memory on the KV blog.

For our family it was a big deal. We virtually never went out, or in fact, ate with Dad. So, it filled two voids for the family.

I remember we always ate in the back room. It was on a rare Sunday, and there seemed to be many other families there as well. I don't ever remember taking our time, and casually eating. We were probably out of there in less than 30 minutes. Tables were turned over and even if there was a small staff, there seemed to be at least one at our table every five minutes.

a comment by Carol Foresta, a former KVer

I grew up on the lower east side. The Garden Cafeteria served as a meeting place both inside and out. My father used to wait outside of it for me each evening, when I was a student returning from college. He'd smoke his pipe and stand in front of one of its doors. There he would meet all of his friends and people from the neighborhood. They would be engrossed in conversation. Because my mother was an excellent cook, my father did not dare to eat at the Garden.The Garden always attracted a colorful assembly of people so very long ago. I believe the people who go there today are probably equally interesting. (Sept., 2007)a comment from Mark, aka "The Cutter," aka "Shoom"

Thanks for the Garden Cafeteria memory on the KV blog.

For our family it was a big deal. We virtually never went out, or in fact, ate with Dad. So, it filled two voids for the family.

I remember we always ate in the back room. It was on a rare Sunday, and there seemed to be many other families there as well. I don't ever remember taking our time, and casually eating. We were probably out of there in less than 30 minutes. Tables were turned over and even if there was a small staff, there seemed to be at least one at our table every five minutes.

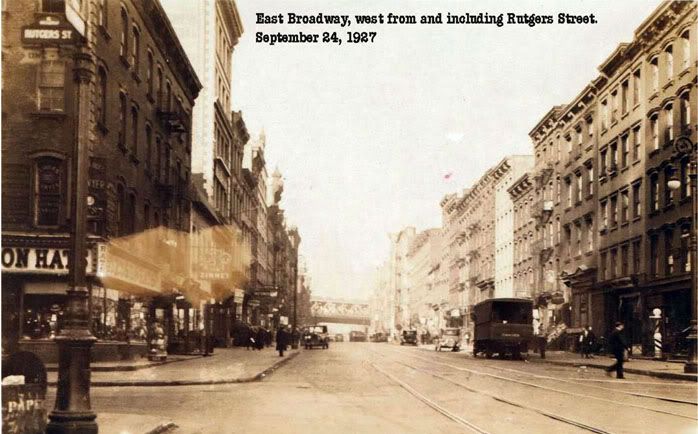

Changes At 181 East Broadway

an excerpt from grub street

Michael Wang already has several locations of Hawa Smoothies (including a popular branch in Wall Street Center), and his latest storefront is now open at 181 East Broadway. The shop is named for Wang's native Hawaii and the interior is bright and inviting, with six cherry-red stools for perching.

Saturday, May 14, 2011

Monday, May 9, 2011

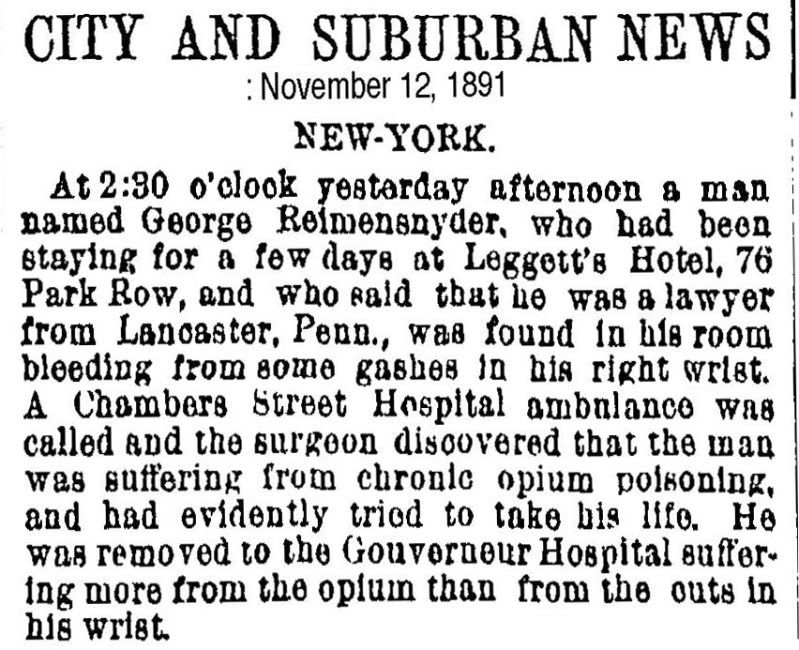

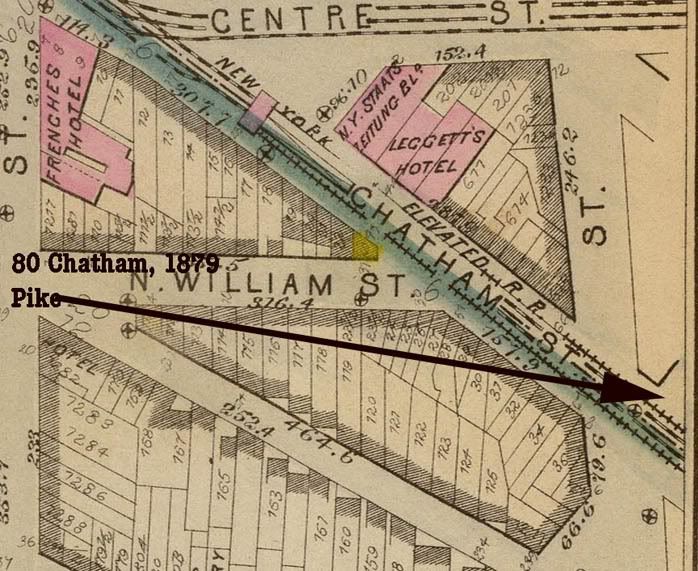

Opium At The Leggett Hotel: 76 Park Row

1881 Opium right across from city hall

approximate site below

The hotel is viewable on this mapalthough it's on Chatham Street, not Park Row. Maybe the hotel above is the French Hotel?

approximate site below

The hotel is viewable on this mapalthough it's on Chatham Street, not Park Row. Maybe the hotel above is the French Hotel?

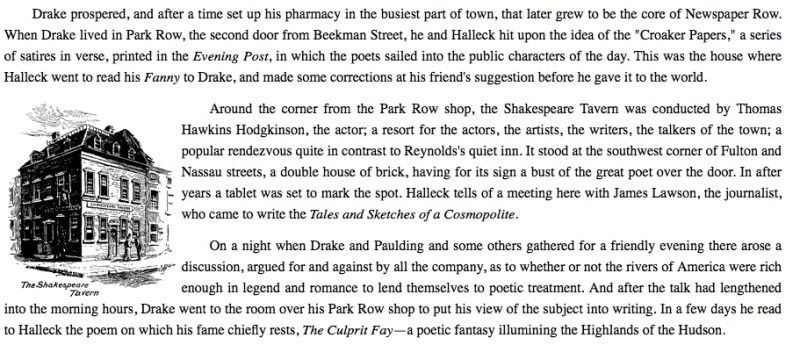

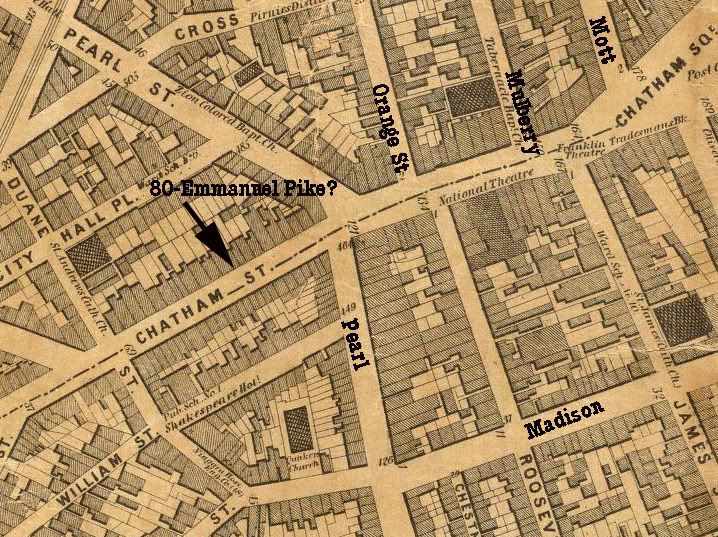

The Shakespeare Tavern On William And Duane Streets

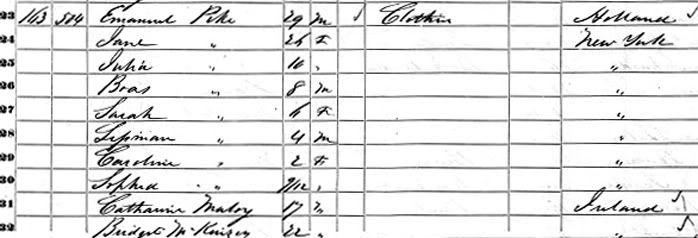

The tavern can be spotted on a 1850's map from a post about Lipman Pike

Sunday, May 8, 2011

Thursday, May 5, 2011

Another Jewish MLB Player From The LES: Jonah Goldman, Part 2

Jonah Goldman Syracuse

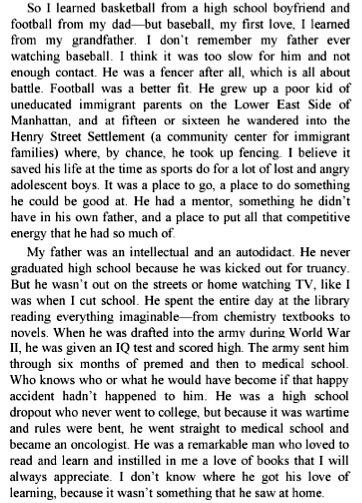

Jonah's dad apparently was a successful photographer. The family left the LES for the more wide open spaces of Brooklyn soon after 1910. Evidently he was well off enough to send Jonah to Syracuse, where Jonah stared in football as well as baseball.

Jonah's dad apparently was a successful photographer. The family left the LES for the more wide open spaces of Brooklyn soon after 1910. Evidently he was well off enough to send Jonah to Syracuse, where Jonah stared in football as well as baseball.

Another Jewish MLB Player From The LES: Jonah Goldman

Jonah Goldman was born on Wednesday, August 29, 1906, in New York, New York. Goldman was 22 years old when he broke into the big leagues on September 22, 1928, with the Cleveland Indians. He died in 1980. For more on Jonah

Tuesday, May 3, 2011

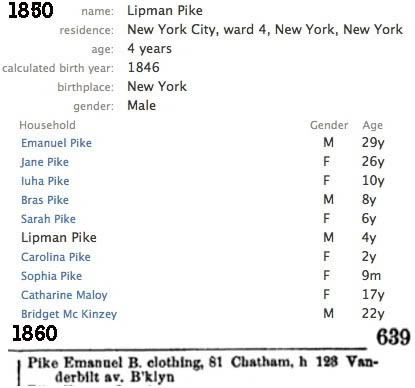

Found: Lipman Pike In The Fourth Ward

When the census proved to be no help, I turned to a directory of businesses. Sure enough I found the Pike family business at 81 Chatham Street in 1860. The family probably lived above the store as was the custom. The Brooklyn store was probably where they moved to when Lip was 5. The father may have still kept the business in Manhattan as well.

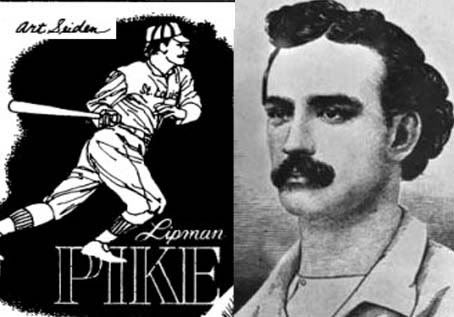

A New Kid's Biography Of Lipman Pike: Lipman Pike: America's First Home Run King

on amazon

an excerpt from a review from the sleeping bear press

an excerpt from a review from the sleeping bear press

Lipman Pike: America's First Home Run King

By Richard Michelson; illustrated by Zachary Pullen

Sleeping Bear Press, Feb. 2011, $16.95

Early in Ernest Thayer's poem Casey at the Bat: A Ballad of the Republic Sung in the Year 1888, a "sickly silence" has fallen on the patrons of the game. But when "mighty Casey," with his "sneer curled" lip and defiance gleaming in his eye, comes to the plate, 5,000 throats and tongues cheer for him and 10,000 eyes focus on his every move.

Casey is such a fan favorite that when he takes the first two pitches - both called strikes - spectators yell out "kill the umpire!" and "fraud!" Casey has to silence both chants and motions to the pitcher to ensure that the game can proceed. Casey confidently stands his ground, as his scorn turns to hate. But however beloved and intimidating he may have been, Casey ends the game by striking out.

The same could not be said of the figure of Lipman Pike - Lip - illustrated by Zachary Pullen in Richard Michelson's new book, Lipman Pike: America's First Home Run King.

On page 17 of the 32-page picture book, Lip, born Lipman Emanuel Pike in 1845, holds a bat in his hand as he poses in front of a dramatic sky worthy of the Hudson River School. Lip, who incidentally bats left, is mustachioed and dressed in the palette of a park ranger (rather than a Texas Ranger). With his black socks pulled up and hunched over to greet the incoming pitch, Lip - though his knuckles are not lined up properly on his bat - is sure to deliver on that much anticipated hit that would later elude Casey.

However many words Pullen's illustration of Lip is worth, Michelson's words beside the picture are quite sobering. Though Lip helped the Philadelphia Athletics win 23 of 25 games, and though he hit six home runs in one game and was the team's best player, Lip's teammates scorned him for being a professional athlete - perhaps the league's first paid player. The left fielder added, "I hear that Pike's a Jew. How can we trust him when we play against Brooklyn?" So, Michelson writes, the Athletics voted Lip off the team.

The First Great Jewish Ballplayer: Lipman Pike, Part 2

Above is the Pike family census from 1850. Lipman was 5 years old. It's somewhere in the fourth ward but no address is given. The mystery will soon be solved.

More on Pike from his wiki page

More on Pike from his wiki page

Lipman Emanuel "Lip" Pike (May 25, 1845 – October 10, 1893) was one of the stars of 19th century baseball in the United States. He was the first player to be revealed as a professional (meaning he was paid money to play), as well as the first Jewish ballplayer. His brother, Jay Pike, played briefly for the Hartford Dark Blues during the 1877 season.

His family was of Dutch background, and his father was a haberdasher. Pike was one of the premier players of his day. He was a great slugger and one of the best home run hitters of his day, so much so that stories about balls he hit were told for quite some time after he stopped playing.

Pike first rose to prominence playing for the Philadelphia Athletics, whom he joined in 1866. He brought an impressive blend of power and speed to the team, hitting many home runs as well as being one of the fastest players around. He was a star who in one game hit 6 home runs; the final score was 67-25.

However, it was soon brought to light that he and two other Philadelphia players were being given $20 a week to play. Since all baseball players were ostensibly amateurs (though many were, like Pike, accepting money under the table), a hearing was set up by the sport's governing body, the National Association of Base Ball Players. In the end, no one showed up to the hearing, and the matter was dropped. By 1869, the Cincinnati Red Stockings became the first openly professional team, and Pike's hearing, farcical as it seems to have been, paved the way for Harry Wright's professionalization of baseball. The Athletics were very successful, but Pike was dropped from the team in 1867, because he was from New York, and thus a 'foreigner,' calling his loyalty into question.

He moved on to the Irvington, New Jersey club and later in 1867 to the New York Mutuals, always a leading team, where he returned for 1868, having caught the eye of Boss Tweed. In 1869 he moved to the Brooklyn Atlantics, another perennial leader, where he hit .610. In 1870, the Atlantics, with Pike manning second base, finally ended Cincinnati's 93-game winning streak.

In 1871, the National Association was formed as the first professional baseball league, and Pike joined the Troy Haymakers for its inaugural season. He was their star and for 4 games was the "captain" (which meant that he managed the team), batting .377 (6th best in the league) and hitting a league-leading 4 home runs. He also led the league in extra base hits (21), and was 2nd in slugging percentage (.654) and doubles (10), 4th in RBIs (39), 5th in triples (7), 6th in on base percentage (.400), 9th in hits (49), and 10th in runs (43). The Haymakers only finished 6th, though, and the team's captaincy switched to Bill Craver.

The Haymakers revamped their roster for the 1872 season, and Pike headed for Baltimore, where he played for the Baltimore Canaries. Pike had another excellent season, leading the league in home runs again (with 6), RBIs (60), and games (56), and coming in 2nd in total bases (127) and extra base hits (26), 3rd in at bats (288), 5th in doubles (15) and triples (5), 9th in slugging percentage (.441) and stolen bases (8), and 10th in hits (84).

In 1873 Pike led the league in home runs for the 3rd consecutive season, hitting 4, and was 2nd in triples (8), 4th in total bases (132), stolen bases (8), and extra base hits (26), 7th in slugging percentage (.462), 8th in doubles (14), RBIs (50), and at bats (286), 9th in hits (90), and 10th in games (56).

Baltimore went bankrupt after the season, so Pike headed off to captain the Hartford Dark Blues for the 1874 season. The Dark Blues were a poor team, but Pike had another fine season, slugging .574 to lead the league, and coming in 2nd with an on base percentage of .368.

Pike abandoned the weak Hartford team after a single season, switching to the St. Louis Brown Stockings. For the first time in his professional career, Pike failed to hit a home run, although he stole 25 bases. He also hit 12 triples and 22 doubles (leading the league) in what was probably his finest offensive season.

In all Lip Pike has the NA career home run (15), and extra base hits (135) records

In 1876, when the National League replaced the National Association, Pike stuck with St. Louis. The Brown Stockings turned in a very good season, finishing a solid 2nd to the Chicago White Stockings. Pike continued to produce offensively, notching totals of 133 total bases (5th in the league) and 34 extra-base hits (2nd).

Seemingly never content to stay with a team very long, Pike headed to the Cincinnati Reds for the 1877 season. The Reds finished last. He hit a powerful and famous home run that year, which apparently went 360 far and 40 feet high, and hit a metal bar at that point which it still had enough force to bend. Pike was still a top-quality player, leading the league in home runs for the 4th time in the 1870s. However, age was starting to catch up with the 32-year-old Pike. He began the season as the 8th-oldest player in the league, and was the 4th oldest player of the 1878 season. The 1878 Reds played very well, though. They finished 2nd, but Pike was replaced by Buttercup Dickerson halfway through the season and forced to look elsewhere for a team. He ended up playing a few games for the Providence Grays, and spent the next 2 years playing for minor league teams.

Pike got a brief call-up in 1881 to play for the Worcester Ruby Legs, but the 36-year-old Pike could no longer play effectively, hitting .111 and not managing a single extra base hit in 18 at-bats over 5 games. His play was so poor as to arouse suspicions, and Pike found himself banned from the National League that September. He was added to the "blacklist" at a 1881 National League meeting, barring him from playing for or against any NL team. He turned to haberdashery, the vocation of his father, and spent another 6 years playing only amateur baseball. He was reinstated in 1883.

In 1887, the New York Metropolitans of the American Association gave Pike another chance. At 42, he was the oldest player in baseball. The only game he played was more of a sending off than a new start, though, and Pike headed back to his haberdashery once more.

In 1936, decades after he died, he received a vote in the elections for the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Pike was also one of the fastest players in the league. He would occasionally race any challenger for a cash prize, routinely coming out the winner. On August 16, 1873, he raced a fast trotting horse named "Clarence" in a 100-yard sprint at Baltimore's Newington Park, and won by four yards with a time of 10 seconds flat, earning $250 ($4,570 in current dollar terms).

Pike died suddenly of heart disease at the age of 48 in 1893. The Brooklyn Eagle reported that "Many wealthy Hebrews and men high in political and old time baseball circles attended the funeral service". He was interred in the Salem Fields Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York.

He was the first famous Jewish baseball player, and was inducted into the International Jewish Sports Hall of Fame.

The First Great Jewish Ballplayer: Lipman Pike

Was born in the Fourth Ward

from Jewish Heroes and Heroines in America, from Colonial Times to 1900:

from Jewish Heroes and Heroines in America, from Colonial Times to 1900:

"Lip" Pike: Baseball's First Pro

by Seymour "Sy" Brody

Lipman E. "Lip" Pike became baseball's first professional player when the Philadelphia Athletics recognized his talent in 1866. The team gave him $20 a week to play third base. Pike was soon followed by others. The baseball players of the time were professional and amateurs.

Pike was born in New York City on May 26, 1845. He was one of five children of Jane and Emanuel Pike, emigres from Holland. His older brother, Boaz, was the first in the family to play baseball on an organized team. The first time that Pike's name appeared in a box score was a week after his bar mitzvah. He had played for the Nationals at first base and his brother had played shortstop. The two brothers played for many teams from 1864 through 1865.

Pike established himself as a home run hitter for the year that he was with Philadelphia Athletics as a professional. Hitting home runs was a rarity in those days. Pike hit them in clusters. He hit six home runs in a game against the Alerts in 1886. Five were hit in a row.

Pike left the Athletics and became the playing manager of the Irvington team in 1867. However, he didn't finish the season with the team. Boss Tweed of New York City made him an offer to play for the Mutuals and he accepted it.

He stayed with the Mutes for one year and left the team to join the Brooklyn Atlantics. The Cincinnati Red Stockings came East and beat every team they played, including the Atlantics, in 1869. The following year, the team returned to Brooklyn and was undefeated in 130 games. They played the Atlantics in a game that went into extra innings. The Atlantics took the lead 8 to 7. Pike played second base and was the key figure in retiring the Reds for Atlantics victory.

The first baseball league composed of only professional players began in 1871. Pike went to Troy, New York, to become the manager of the team there. During this period, teams quickly came into being and then quickly disappeared. There wasn't a reserve clause. Many players were drifters, drunkards, and gamblers. Pike was an exception. Pike moved to Baltimore for the 1872-73 season and played in the outfield. He was a very fast runner. It is told that Pike won $200 when he defeated a horse in a race.

Pike played and managed many teams after his stay in Baltimore. He moved around the East Coast, going from one team to another. He finished the year with the Worcester, Massachusetts, team in 1881. The team had a bad season and Pike was made the scapegoat. Pike was the first to be put on baseball's blacklist.

He opened up a haberdashery store and announced his retirement from baseball. The store was a gathering place for baseball enthusiasts. Pike made an attempt to play again when he was 42 years old. He joined the original New York Mets, later announcing his retirement.

Pike became an umpire in the National League and the American Association while still operating his haberdashery. He died of a heart attack at the age of 48. "He was eulogized in many newspapers." the Sporting News said. "He was one of the baseball players in those days, who was always gentlemanly on and off the field - a species which is becoming rarer as the game grows older..." Pike will always be remembered as the first professional player in baseball.

This is one of the 150 illustrated true stories of American heroism included in Jewish Heroes and Heroines of America, © 1996, written by Seymour "Sy" Brody of Delray Beach, Florida, illustrated by Art Seiden of Woodmere, New York, and published by Lifetime Books, Inc., Hollywood, FL.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)