Showing posts with label revolutionary war era. Show all posts

Showing posts with label revolutionary war era. Show all posts

Sunday, January 2, 2011

Sunday, April 11, 2010

The Native Peoples Of Lower Manhattan

above image and information below are from Eric Ferrara at the the lower east side history project

Gentrification? The native peoples of Lower Manhattan

Native American peoples inhabited the New York City area for a thousand years before America was "discovered" by Christopher Columbus.

These people were the Lenape tribes of Algonquin lineage, who were considered to be the "grandfathers" of all the various Algonquin-speaking tribes. It was Lenape canoes that met Verrazano in NY Harbor during the very first recorded contact with Europeans in 1524.

The complicated Native American social structure is easier to identify and group by language-spoken rather than by "tribe," but for the sake of this article, I will lazily associate each group as "tribe" anyway. :)

The Native peoples of early Manhattan island hunted big game like Moose and deer, and harpooned bottlehead whales off the shores. They grew maize and trapped small game like beaver. Since nature was sacred to the Lenape, who believed animals held spiritual significance, not one bit of their game was wasted. Pelts, bones, and meat were used in every way possible. In fact the Dutch were impressed by the minimal footprint the Lenape left after living here for hundreds of years. Nothing was destroyed that was not necessary for survival or ritual.

According to Dutch accounts, "The environment was pristine. The air smelled unusually sweet and dry, and schools of playful dolphins escorted ships into the harbor. The air was so filled with birds that sometimes you could hardly hear a conversation."

Large settlements of Native Americans sprouted up at strategic locations along today's Hudson and East River banks. The streets we call the Bowery and 4th Avenue today were the exact route the natives used to travel North and South and Astor Place was a sacred meeting place called "Kintecoying" (meaning "Crossroads of Three Nations").

It was here at Astor Place, or Kintecoying (see map, right), that these three diverse sects of Lenape met around a tall oak tree, a sacred symbol to the people of the day, and told stories of ancient tradition and held spiritual ceremonies. This is where the tribes would share important news and information from around the territories, where tribal councils were set up to decide disagreements, and where valuable goods were traded.

The closest tribe to Kintecoying was the Renneiu-speaking Canarsie tribes, who predominantly settled on the east side of the Bowery, with two major Villages: Shempoes, which was located between modern day 10th to 14th Streets along 2nd Avenue; and Rechtanck, located on the coast around modern day Clinton and Montgomery streets.

To the West of the Bowery were the Unami-speaking Sapohannikan tribes. Their territory was approximately between today's W.14th Street and Canal streets, with their main village, Sapohannikan, established along the coast of the Hudson River approximately where Horatio and Greenwhich streets sit today. And North of today's Union Square were the Munsee speaking Lenape tribes.

The trail from Shempoes Village started about where St. Marks Church sits today and cut straight through 9th Street and St. Marks Place, then West into Astor Place.

The Sapohannikan trail originated around Horatio Street heading North to 13th Street before essentially following Greenwich Avenue all the way to Washington Square Park -- which the path cut straight through -- before heading East again to Astor Place.

The Lenape were not helpless people; Manhattan island was a thriving center of agriculture and commerce; The Canarsie had set up shipping routes to export local goods as early as 1300 AD, 300 years before the first Europeans settled New Amsterdam.

To put it in perspective, once the Dutch arrived for good in 1613, there were about 15,000 Lenape inhabiting the area. It took only a few short years before most of Manhattan island's natural resources were exhausted and the native people were wiped or forced out. By 1700, less than 200 Lenape remained.

I can only imagine the nerve of guys like Columbus, Verrazano, et al. Think about it. That is like you or I driving into a small town upstate, setting up a shop a main street, telling the locals they now live in "Joe town," then inviting all of our friends from the city to join us. (Oh, then we negotiate deals with neighboring towns to kill all of the locals so there is no opposition. Then we kill the people who helped us because we need to expand to accommodate more of our friends.)

Want to talk about gentrification?

The Last Of The Mohicans

Last Mohicans 1

a link to marvel's teacher's guide

The Mohicans were related to the Lenape Indians who inhabited Manhattan prior to the arrival of the Dutch. About the Mohicans

a link to marvel's teacher's guide

The Mohicans were related to the Lenape Indians who inhabited Manhattan prior to the arrival of the Dutch. About the Mohicans

The Mahicans (also Mohicans) are an Eastern Algonquian Native American tribe, originally settling in the Hudson River Valley (around Albany, NY). After 1680, many moved to Stockbridge, Massachusetts. During the early 1820s and 1830s, most of the remaining descendants migrated westward to northeastern Wisconsin. The tribe's name for itself (autonym) was Muhhekunneuw, or "People of the River." Their current name is the name applied to the Wolf Clan division of the tribe, from the Mahican manhigan.

The Mahican were living in and around the Hudson Valley at the time of their first contact with Europeans in 1609, who were mostly Dutch. Over the next hundred years, tensions between the Mahican and the Iroquois Mohawk, as well as Dutch and English settlers, caused the Mahican to migrate eastward across the Hudson River into western Massachusetts and Connecticut. Many settled in the town of Stockbridge, Massachusetts, where they became known as the Stockbridge Indians.

The Stockbridge Indians allowed Protestant Christian missionaries, including Jonathan Edwards, to live among them. In the 18th century, many converted to Christianity, while keeping certain traditions of their own. Although they fought on the side of the American colonists in both the French and Indian War (North American part of the Seven Years' War) and the American Revolution, citizens of the new United States forced them off their land and westward. First the Stockbridge settled in the 1780s at New Stockbridge, New York, on land allocated by the Oneida, of the Iroquois Confederacy.

In the 1820s and 1830s, most of the Stockbridge moved to Shawano County, Wisconsin, where they were promised land by the US government. In Wisconsin, they settled on reservations with the Munsee. Together, the two formed a band jointly known as Stockbridge-Munsee. Today the reservation is known as that of the Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohican Indians (Stockbridge-Munsee Community).

Moravian Church missionaries from Bethlehem in present-day Pennsylvania founded a mission at the Mahican village of Shekomeko in Dutchess County, New York. They wanted to bring the Native Americans to Christianity. Gradually they were successful in their efforts, converting the first Christian Indian congregation in the United States. They built a chapel for the people in 1743. They also diligently defended the Mahican against European settlers' exploitation, trying to protect them against land encroachment and abuses of liquor. Some who opposed their work accused them of being secret Catholic Jesuits (who had been outlawed from the colony in 1700) and of working with the Indians on the side of the French. The missionaries were summoned more than once before colonial government, but also had supporters. Finally the colonial government at Poughkeepsie expelled the missionaries from New York in the late 1740s. Settlers soon took over the Mahican land.

The now extinct Mahican language belonged to the Eastern Algonquian branch of the Algonquian language family. It was an Algonquian N-dialect, as were Massachusett and Wampanoag. In many ways, it was more similar to, and just as easily considered one, of the L-dialects, such as that of the Lenape.

Labels:

comics,

native americans,

revolutionary war era

Saturday, March 20, 2010

Monday, January 4, 2010

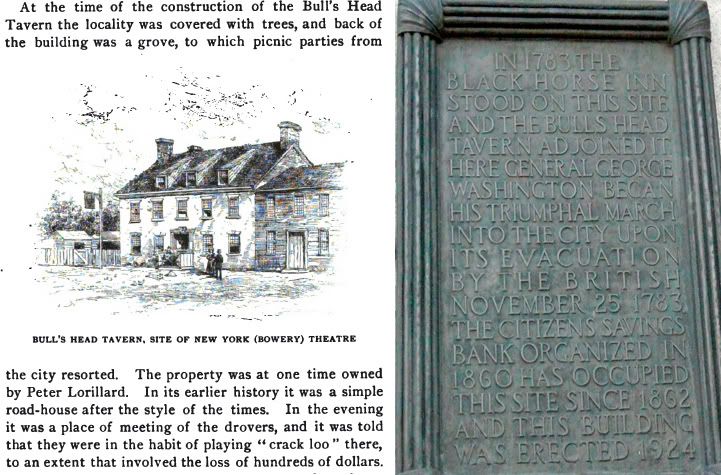

Bull's Head Tavern: Then And Now

from the bowery boys

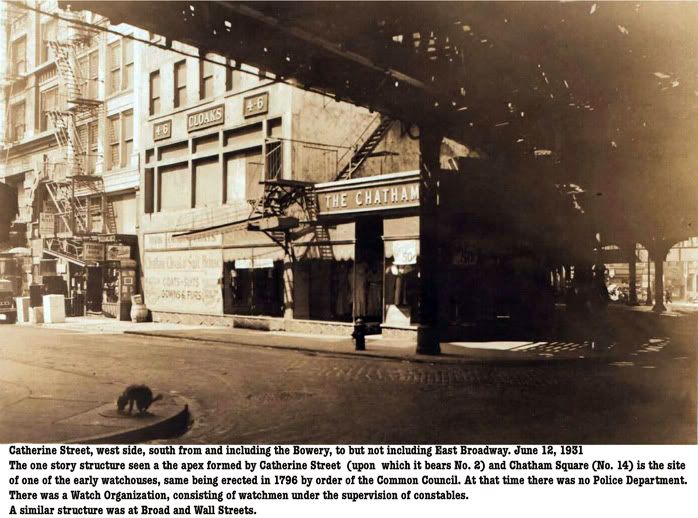

The Bull's Head Tavern was the gathering-place for farmers, drovers, and merchants in the 18th century, located well outside city boundaries just east of Collect Pond. (At the Bowery, right at the entrance to the Manhattan Bridge.)

It soon became the center of Manhattan's entire meat selling and rendering industry, with the area surrounding the nearby Collect overrun with tanneries and slaughterhouses. As the Bull's Head was also located right on the Boston Post Road (later the Bowery), situated at a crossroads of livestock yards and stables, it became an ideal place for both commerce and carousing.

The Bull's Head was in operation as early as 1755, enjoying business as "the last halting-place for the stages before entering the city."

Within the next few decades, industry enveloped the area, transforming the Bull's Head into a cattle market, with pens adjoining the main building where farmers from the surrounding area herded their best specimens for sale. Inside the tavern became a literal stock market, with transactions, news and gossip being shared over brew and a hot meal. Those who lingered well into the night sometimes played a strange game called crack loo -- often gambling away any profits they might have made earlier in the day. Out in the pen, dog fights and "bear baiting" sometimes occured as entertainment.

As Washington Irving describes, at the Bull's Head he would "hear tales of travelers, watch the coaches and envy the more pretentious country gentlemen in Castor hat, cherry-derry jackets and doeskin breeches."

On November 25, 1783, Evacuation Day, the Bull's Head entered history. As the British fled New York that day, George Washington and his entourage met at the Bull's Head, preparing themselves for their triumphant entry into town. Governor George Clinton and over 800 uniformed troops and townfolk gathered right outside, preparing for the procession.

Henry Astor, the older brother of John Jacob, stepped in as owner of the Bull's Head in 1785. Already an accomplished butcher, Henry served his "celebrated cuts of meats" and often outpriced his own clientele when a particularly choice herd of cattle came travelling by.

Of course, New York was outgrowing its old boundaries by then. By 1813, Collect Pond had been drained and high society eyed the Bowery, sweeping away the filthy stockyards and factories to construct homes, shops and theatres. Moving with the changing times, some civic minded businessmen bought out Astor and moved the Bull's Head somewhere safely outside the city -- this time at 3rd Avenue and 24th Street!

In 1830, this new location fell into the hands young rancher and entrepreneur Daniel Drew, who turned the tavern into a sort of bank, marketplace and social club for local cattlemen, upgrading the establishment and building his own reputation as a saavy financier.

As this time, according to an old history, "various types of men mingled in the bar-rroom of the Bull's Head, from the rough country man to the speculative citizen, butcher and horse-fancier. Plain apple-jack and brandy and water... were the principal liquors passed over the bar. Guests were so numerous that at the first peal of the dinner-bell. it was neccessary to rush for the table or fail miserably." And of course, after hearty meal and vigorous drink, came the gambling, "throwing dice for small stakes."

Drew eventually went on to become a steamboat mogul. The location of the old Bull's Head became the notorious Bowery Theatre. It's uptown location on 24th, of course, caved in to a growing residential neighborhood. However, today there is a new Bull's Head Tavern, at that exact location, that probably smells a lot better than the original.

And not to forget, there was also a Bull's Head Tavern in Staten Island, at Victory Boulevard and Richmond Avenue. Built in 1741, this Bull's Head was a popular destination for British-loving Tories before the days of the Revolutionary War. Before it was destroyed in a fire, "people from all over the country made special trips to the old house, just to see the famous Tory headquarters," according to one old history.

The neighborhood that sprouts around that intersection at Victory and Richmond is named Bulls Head in the old tavern's honor.

Thursday, October 8, 2009

A Date With Judy

I met Judy and recorded this back on September 22nd when I went on an African American history tour of Lower Manhattan

She was in the IGC class at PS 177 and then went on to JHS 65. She grew up in the Smith projects and was a choir member at Mariner's Temple. Also along on the tour was another lower east sider, from "uptown" around 6th Street named Cynthia. By coincidence, Cynthia lived in the same building as my cousins.In an email she wrote:

I totally forgot about Club Lunch and we used to shop in Honey's all the time. I still have furniture from there after a million years.

Recently while practicing my fourth ward walking tour with Marty he recalled Honey's and how he had once bought a green striped shirt there that became one of his favorites.

Labels:

honey's,

neighborhood tours,

revolutionary war era

Wednesday, October 7, 2009

Thursday, September 17, 2009

1782 Map Showing Old Streets In The Fourth Ward

A section of a map that I discovered at the brooklyn genealogy site In 1782 Pearl Street used to be Queen Street, Rose Street was Princess, William Street was King George. A great site for learning about those old street names is Gilbert Tauber's oldstreets.com

Labels:

lost streets,

maps,

revolutionary war era,

Ward 4

The Sugar House As A Prison During The Revolutionary War

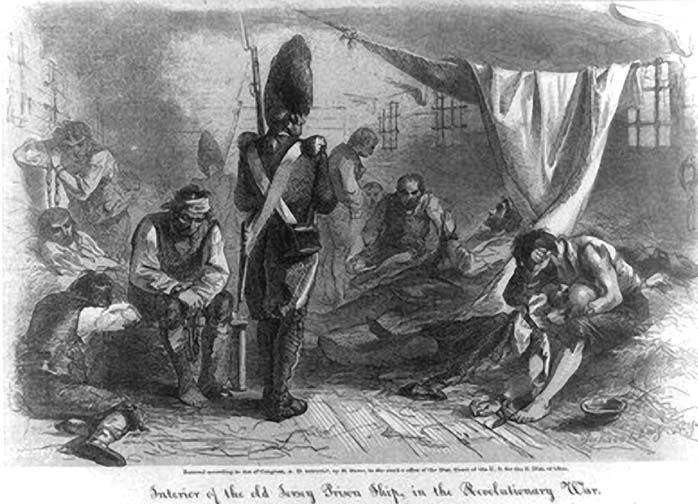

Below, prisoners on one of the infamous British prison ships

Forgotten Patriots: The Untold Story of American Prisoners During the Revolutionary War, by Edwin Burrows tells the harrowing account of the fate of those prisoners

Forgotten Patriots: The Untold Story of American Prisoners During the Revolutionary War, by Edwin Burrows tells the harrowing account of the fate of those prisonersBetween 1775 and 1783, some 200,000 Americans took up arms against the British Crown. Just over 6,800 of those men died in battle. About 25,000 became prisoners of war, most of them confined in New York City under conditions so atrocious that they perished by the thousands. Evidence suggests that at least 17,500 Americans may have died in these prisons—more than twice the number to die on the battlefield. It was in New York, not Boston or Philadelphia, where most Americans gave their lives for the cause of independence.

New York City became the jailhouse of the American Revolution because it was the principal base of the Crown’s military operations. Beginning with the bumper crop of American captives taken during the 1776 invasion of New York, captured Americans were stuffed into a hastily assembled collection of public buildings, sugar houses, and prison ships. The prisoners were shockingly overcrowded and chronically underfed—those who escaped alive told of comrades so hungry they ate their own clothes and shoes.

Despite the extraordinary number of lives lost, Forgotten Patriots is the first-ever account of what took place in these hell-holes. The result is a unique perspective on the Revolutionary War as well as a sobering commentary on how Americans have remembered our struggle for independence—and how much we have forgotten.

Wednesday, September 16, 2009

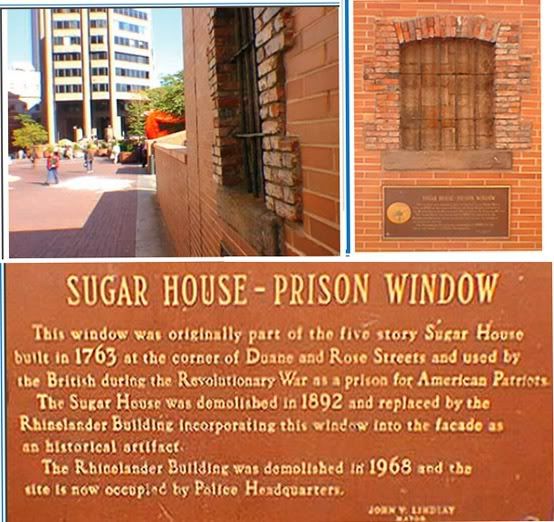

Sugar House Prison Window

From Prof. Forman's Queen's College site

Hidden away behind the Municipal Building is an inconspicuous monument to an atrocity, the Rhinelander Sugar House massacre. During the Revolutionary War, while the city was under the occupation of English troops, the Sons of Liberty conducted a campaign to intimidate Tory residents and harass the occupying army. Some of this was almost playful, such as the erection of "Liberty Poles," stolen pinewood masts furtively set up in public places. Once such place was in northeastern City Hall Park, then simply called the Common, where the statue of Nathan Hale presently stands. This would have been less than five hundred feet from where the Redcoats were bivouacked.

Often, though, the actions of the Sons of Liberty more closely resembled what we might nowadays call terrorism. Homes and businesses belonging to British sympathizers were destroyed by fire in the middle of the night, and in 1776 an enormous fire spread north from Pearl as far as Vesey Street engulfing the first Trinity Church on Wall Street and threatening St. Paul's Chapel.

New York was, however, a city that generally supported England and its Royalist citizens demanded that the occupying army take strong measures against the Sons of Liberty. Makeshift prisons appeared in various places of the city, among them the commandeered Rhinelander Sugar House, a warehouse for the storage of Caribbean sugar that stood at Duane and Rose Streets until 1896. The prisoners in the sugar house were allowed to starve. Indeed, during the English occupation of New York City from 1776 to 1783, it is estimated that 11,000 revolutionists died in such prisons.

When the sugar house was demolished, a loft called the Rhinelander Building replaced it. Several of the sugar house prison windows were incorporated into the loft building, which itself was demolished in 1968 at the construction of One Police Plaza, the central New York City police headquarters . One section of the sugar house wall was transported to Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx and re-erected near the Van Cortlandt mansion. A single window and its surrounding brickwork was incorporated into a small monument just behind the subway arcade of the Municipal Building.

In its time the Rhinelander Sugar House became a symbol of atrocity. It would not be an exaggeration to consider it the Abu Ghraib of its era. Passersby continually reported seeing ghostly shadows in the windows of the old sugar house. One thinks of things like this in times like these.

Saturday, July 18, 2009

Nathan Hale Died Here 4

Nathan Hale Post

Pictures that include some of the various sites where there are statues of Nathan Hale and where various groups think his demise was met.

Pictures that include some of the various sites where there are statues of Nathan Hale and where various groups think his demise was met.

Friday, July 17, 2009

Nathan Hale Died Here 3

from the nytimes of 11/23/1997

MAKING IT WORK; Nathan Hale Was Here . . . and Here . . . and Here

By DAVID KIRBY

DID the American patriot Nathan Hale meet his fate where a Gap store now stands on Third Avenue at 66th Street? Did he lose his one life for his country at the site of the Yale Club in midtown? Or did the British string him up downtown, at what is now City Hall Park?

Even now, no one knows for sure.

For at least 150 years, historians and Revolutionary War buffs have debated where Hale was hanged as a spy in 1776. History books, biographies and encyclopedias are literally all over the place when it comes to the site of Hale's execution.

There are three places in New York where our hero was supposedly captured, four where he may have been detained and no less than six where he is said to have been hanged.

Many people assume Hale was executed by British troops in present-day City Hall Park. They have good reason: the park was so widely believed to be the site of the hanging that on Nov. 25, 1893, a monument to the ''Martyr Spy'' was erected there.

The next morning, there were glowing accounts in The New York Herald of the grandiose dedication of the monument. But the same day, the paper ran a letter from William Kelby, the librarian of the New-York Historical Society, who said he had proof that Hale went to the gallows near what is now East 66th Street.

The son of a wealthy Connecticut farmer, Hale was said to have been a dashing ladies' man. When Washington put out a call for spies to monitor enemy movements after British troops crushed American rebels in August 1776, Hale was the only volunteer.

Capt. Nathan Hale went to Long Island, passing himself off as a Dutch schoolteacher as he ambled undetected amid the redcoats, probably near the site of the Unisphere in Flushing Meadows Corona Park.

On Sept. 15, 1776, Gen. William Howe brought the British army across the East River, landing at Kips Bay and setting up headquarters at the mansion of the rebel Beekman family, near what is now First Avenue and 51st Street.

Six days later, Hale was arrested by the British, who found military notes in Latin in his shoes. The rest is history, or mystery.

Some say Hale was captured on Long Island. Others say he was caught after crossing the East River and landing smack in a nest of British soldiers, who may have been camped out a cocktail's throw from what is now Elaine's. The most popular theory is that Hale was taken prisoner in what today is downtown New York, during a fire set by the Yankees on Sept. 21, 1776, that destroyed much of the city.

Depending on who you ask, Hale might have spent his final night in the jail on the Commons, where today Mayor Giuliani issues edicts; at Bayard's Sugar Mill on Wall Street, near the site of the New York Stock Exchange; at the Beekman mansion greenhouse or at the Sign of the Dove Tavern, across Third Avenue from where the Gap now stands at 66th Street.

We do know that Hale was hanged on Sept. 22, 1776, after rejecting an offer to switch sides to save his rebel skin. He was just 21.

Speculation about the hanging site seems to have begun in 1825, when one Gabriel Furman of Brooklyn somehow divined that Hale was killed ''on the Brooklyn shore, to the southwest of the old ferry house.''

Not so, Henry Onderdonk Jr., a historian, said in his 1846 book ''Revolutionary Incidents of Queens County.'' According to Onderdonk, ''He was hanged upon an apple tree in the orchard of Colonel Rutgers, on the present East Broadway in this city.''

In 1850, Benjamin Thompson, known as the historian of Long Island, identified the spot as being ''in the neighborhood of Madison and Market Streets.''

Then, on Nov. 25, 1893 -- the 110th anniversary of the British evacuation of New York -- Kelby dropped his bombshell: an entry dated Sept. 22, 1776 that he found in the British headquarters ''orderly book.''

''A Spy fm the Enemy (by his own full confession) apprehended Last night, was this day Executed at 11 oClock in front of the Artilery Park,'' it said.

But where was the artillery park? Another entry, from Oct. 11, 1776, refers to one ''near the Dove,'' evidently the tavern. A third entry mentions artillery ''near the five-mile stone,'' the marker five miles north of New York and supposedly near the Dove, on the Boston Post Road, which is Third Avenue, at present-day 66th Street.

So did Kelby solve the mystery? Not really. ''There was a whole series of parks, camps, ammo dumps and bivouacs scattered all over,'' including lower Manhattan, said Ted Burrows, a professor of history at Brooklyn College and an authority on the British occupation. ''We can't know for sure where this particular artillery park was.''

As for the Sign of the Dove restaurant on Third Avenue and 65th Street, it was named after the original, though when Joseph Santo opened it in 1962, he did not know the Hale connection, said Henny Santo, Joseph's sister-in-law. ''Then this woman called us researching a book on Hale,'' Ms. Santo said. ''She claimed to have a British officer's journal saying he'd witnessed Hale's execution, across the Post Road from the Dove.''

But that 1979 book, ''Nathan Hale,'' is out of print, its publishing house has folded, and the author, Susan Poole, has an unlisted number in Cambridge, Mass. Becky Akers, a self-described Hale fanatic who has written about the Revolutionary War period for history journals, is hardly convinced. ''If that journal entry existed, every historian would know of it, and they don't,'' she said.

She added: ''My fantasy is to go in under the Gap with a bulldozer and try to find his bones. But I have a horrible feeling the British just tossed him in the East River.''

To complicate matters further, there is the plaque that has long been on the wall of the Yale Club at Vanderbilt Avenue and East 44th Street, saying that Hale, a Yale graduate, was executed nearby.

No one seems to know anymore why the plaque was put there. Maybe it was overreaching Eli pride, or confusion over a Colonial newspaper advertisement that said the Dove tavern was ''near the four mile stone,'' which would be about 44th Street today.

And in yet another Hale mystery, a bronze of Nathan Hale disappeared from a small alcove at the Yale Club a few years back. The talk at the bar was that it was stolen, and some say it has been replaced. ''I can't comment on bar buzz,'' said Frederick A. Leone, the club's president. ''All I can say is that there's a statue of Nathan Hale on the second floor.''

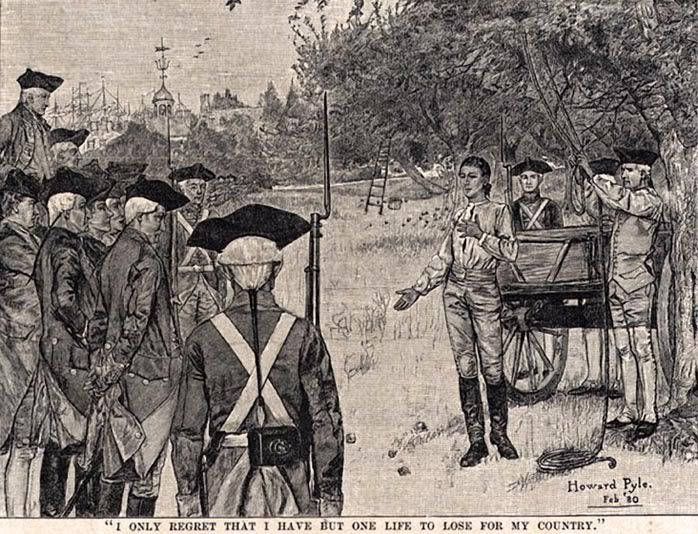

If it's not certain where Nathan Hale was executed, then how do we know that he uttered those famous last words about having only one life to lose?

There are different versions of what Hale said on the gallows. According to the journal of Frederick Mackenzie, a British officer who witnessed Hale's hanging, Hale said, ''It is the duty of every good officer to obey any orders given him by his commander in chief.''

The line most people remember -- ''I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country'' -- actually comes from the memoirs of Hale's friend William Hull, who wrote 50 years after Hale was hanged that he ''was calm, and bore himself with gentle dignity.''

But an anonymous article in The Boston Chronicle six years after Hale's death quotes him as saying: ''I am so satisfied with the cause in which I have engaged, that my only regret is that I have not more lives than one to offer in its service.''

Maybe Hull figured his version would be more easily memorized by future American schoolchildren.

As to where the hanging took place, theories abound.

Nathan Hale Died Here 2

The Execution of Nathan Hale, 1776

In the early summer of 1776, the British evacuated Boston leaving the city and New England to the rebelling colonialists. Where would the British strike next? The mystery was solved when a British naval force appeared off the coast of Staten Island in late June - New York would be their target. The city had great strategic value. Its deep harbor could shelter the British fleet and its capture would pave the way for the Red Coats to battle northward up the Hudson and link with a force moving south from Canada. This would separate New England from the rest of the colonies.

In late June, the British occupied Staten Island in a landing unopposed by the Colonials. In late August a combined force of British and Hessian troops crossed Lower New York Bay and invaded Long Island. The British attacked the Americans from two sides forcing the Colonials to cross over to Manhattan Island. In early September, General Washington retreated again, this time across the Harlem River leaving New York City to the British.

Nathan Hale was a lieutenant in the Continental Army. In his early twenties, Hale had worked as a schoolteacher before the Revolution. In late September 1776 he volunteered to cross the British lines and travel to Long Island in order to gather intelligence. Unfortunately, his mission was soon discovered and he was captured by the British. Taken to General Howe's headquarters (commander of the British forces) in New York, the young spy was interrogated and executed on September 22. Word of the execution was brought to General Washington's headquarters shortly after by a British officer carrying a flag of truce. Captain William Hull of the Continental Army was present and recalled the event:

"In a few days an officer came to our camp, under a flag of truce, and informed Hamilton, then a captain of artillery, but afterwards the aid of General Washington, that Captain Hale had been arrested within the British lines condemned as a spy, and executed that morning.

I learned the melancholy particulars from this officer, who was present at his execution and seemed touched by the circumstances attending it.

He said that Captain Hale had passed through their army, both of Long Island and York Island. That he had procured sketches of the fortifications, and made memoranda of their number and different positions. When apprehended, he was taken before Sir William Howe, and these papers, found concealed about his person, betrayed his intentions. He at once declared his name, rank in the American army, and his object in coming within the British lines.

Sir William Howe, without the form of a trial, gave orders for his execution the following morning. He was placed in the custody of the Provost Marshal, who was a refugee and hardened to human suffering and every softening sentiment of the heart. Captain Hale, alone, without sympathy or support, save that from above, on the near approach of death asked for a clergyman to attend him. It was refused. He then requested a Bible; that too was refused by his inhuman jailer.

'On the morning of his execution,' continued the officer, 'my station was near the fatal spot, and I requested the Provost Marshal to permit the prisoner to sit in my marquee, while he was making the necessary preparations. Captain Hale entered: he was calm, and bore himself with gentle dignity, in the consciousness of rectitude and high intentions. He asked for writing materials, which I furnished him: he wrote two letters, one to his mother and one to a brother officer.' He was shortly after summoned to the gallows. But a few persons were around him, yet his, characteristic dying words were remembered. He said, 'I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country.'"

Nathan Hale Died Here 1

Sea Land Church Hale

According to this 1919 nytimes' article Nathan Hale died somewhere near Market and East Broadway, but...

According to this 1919 nytimes' article Nathan Hale died somewhere near Market and East Broadway, but...

Labels:

nathan hale,

nytimes,

revolutionary war era,

Ward 7

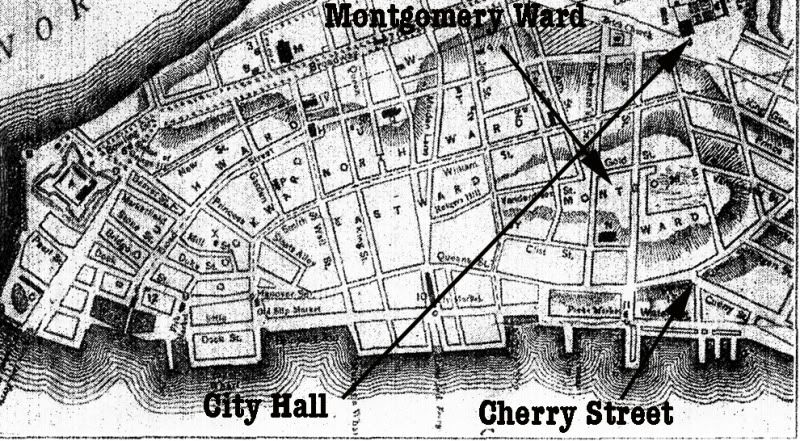

1775 Map Showing Montgomery Ward

from map info from gutenberg project

This survey, made in the winter of 1775, shows the city proper as it existed during the Revolutionary War. Places indicated by the lettering are described under the original as follows: A, Fort George. B, Batteries [at the two points of the island]. C, Military Hospital [south of Pearl St.]. D, Secretary's Office [near Fort George]. E, [Not Shown]. F, Soldiers' Barracks [at extreme right]. G, Ship Yards [lower right hand corner]. H, City Hall [Broad and Wall streets, site of present Sub-Treasury building]. I, Exchange. J, K, Jail and Workhouse [both situated on the "intended square or common," now City Hall Square]. L, College [Church and Murray streets; this was King's College, now Columbia University]. M, Trinity Church [the present Trinity was built on 1839-46, though it stands on the site of the old church built in 1696]. N, St. George's Chapel. O, St. Paul's Chapel [built in 1756, the oldest edifice still standing in N.Y.C.]. P to Z, various churches.

I guess Montgomery Ward is named after Richard Montgomery, the war hero and not Aaron Montgomery Ward (February 17, 1844 - December 7, 1913) the businessman notable for the invention of mail order. About Richard Montgomery:

Richard Montgomery (December 2, 1738 – December 31, 1775) was an Irish-born soldier who first served in the British Army. He later became a brigadier-general in the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War and he is most famous for leading the 1775 invasion of Canada.

Montgomery was born and raised in Ireland. In 1754, he enrolled at Trinity College, Dublin, and two years later joined the British army to fight in the French and Indian War. He steadily rose through the ranks, serving in North America and then the Caribbean. After the war he was stationed at Fort Detroit during Pontiac's Rebellion, following which he returned to Britain for health reasons. In 1773, Montgomery returned to the Thirteen Colonies, married Janet Livingston, and began farming.

When the American Revolutionary War broke out, Montgomery took up the Patriot cause, and was elected to the New York Provincial Congress in May 1775. In June 1775, he was commissioned as a Brigadier General in the Continental Army. After Phillip Schuyler became too ill to lead the invasion of Canada, Montgomery took over. He captured Fort St. Johns and then Montreal in November 1775, and then advanced to Quebec City where he joined another force under the command of Benedict Arnold. On December 31, he led an attack on the city, but was killed during the battle. The British found his body and gave it an honorable burial.

Wednesday, July 15, 2009

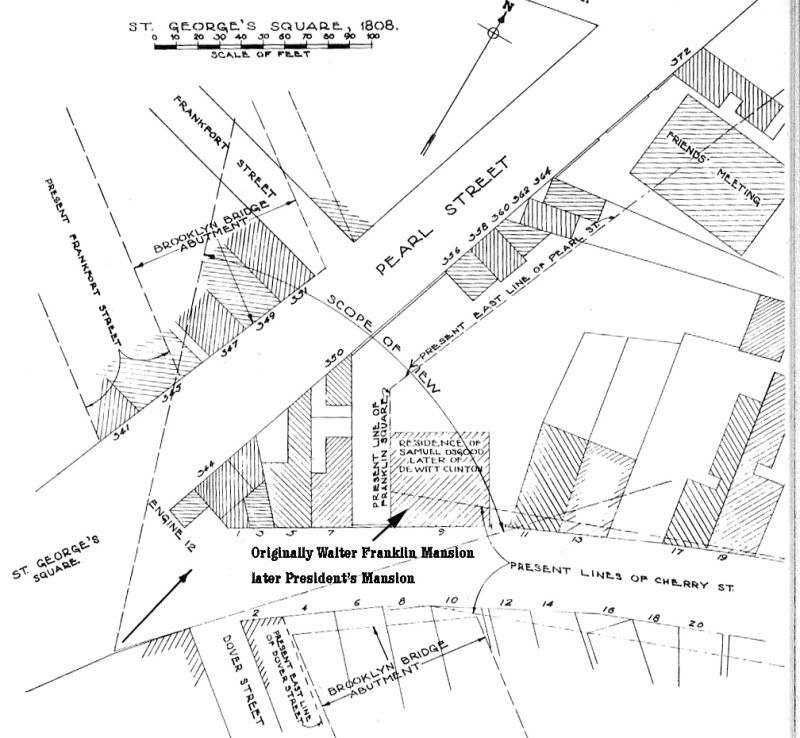

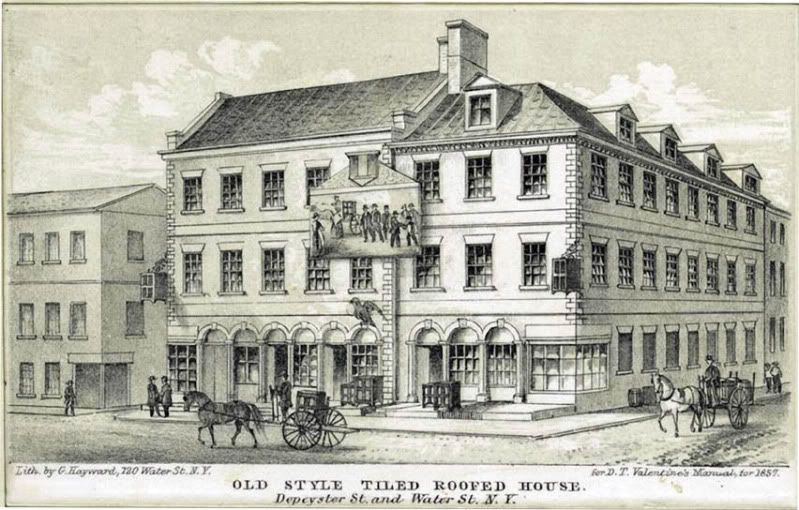

The Depeyster Mansion

This was not too far away from the Cherry Hill section where Washington's first mansion was. Catherine Depeyster was born into the Rutgers family and I once thought Catherine Street was named after her. It wasn't. It was named after Catherine Desbrosses, daughter of Jacques Desbrosses, a 17th Century Hugueonot immigrant who had a rum distillery near the East River.

Labels:

cherry hill,

naming new york,

nypl,

revolutionary war era

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)