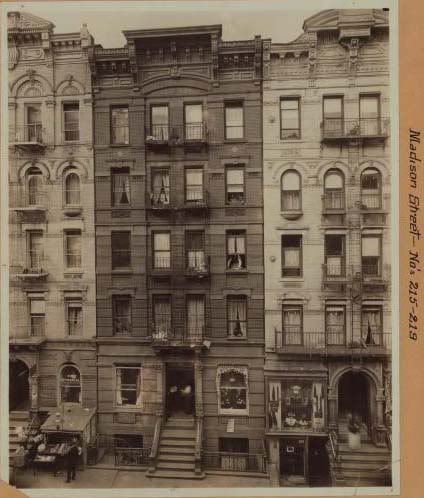

This is where Isidore Zimmerman lived after he was released from prison in 1963

His NYTimes' obituary

His NYTimes' obituaryISIDORE ZIMMERMAN, 66, MAN UNJUSTLY JAILED FOR A MURDER

By ROBERT D. MCFADDEN

Published: October 14, 1983

Isidore Zimmerman, who spent nine months on death row and 24 years in New York State prisons for a 1937 murder he did not commit, died of a heart attack Wednesday, four months after winning $1 million from the state for his unjust imprisonment.

Mr. Zimmerman, a 66-year-old retired doorman, collapsed on a street near his home in Jackson Heights, Queens, as he returned from shopping, his lawyer, Alfred R. Fabricant, said yesterday.

Mr. Zimmerman, who was released from prison in 1962, had spent 20 years fighting for compensation for his ordeal, which he said included severe beatings, long periods of solitary confinement in ''strip cells'' and diets of bread and water.

He had asked for $10 million but was awarded $1 million by the State Court of Claims last May 31. He was paid on June 30 and, after deducting legal and other expenses, received about $660,000.

'Black Cloud Over Him'

''He bought a new car, he took a trip to the Catskills for a few days - that's about as much as he got to do,'' said Mr. Fabricant, a lawyer with the firm of Shea & Gould. ''He always said he had this black cloud over him.''

Mr. Zimmerman, who wrote a book, ''Punishment Without Crime,'' told in repeated lawsuits against the state of the injustices he said had been done to him.

The murder that led to Mr. Zimmerman's imprisonment occurred on April 10, 1937. During a robbery by a group of men at a restaurant on Manhattan's Lower East Side, a police detective, Michael J. Foley, was shot to death. Six men were arrested, and one of them, apparently to conceal his own involvement, falsely accused Mr. Zimmerman of supplying weapons to the gang.

Mr. Zimmerman contended he was innocent, but he was convicted with the other six of first-degree murder. Five of the men died in the electric chair and one died in prison. Mr. Zimmerman also was sentenced to death, but two hours before his scheduled execution it was commuted to life in prison by Gov. Herbert H. Lehman.

In 1962, with the aid of a lawyer, Maurice Edelbaum, who took his case without a fee, an appeals court overturned the conviction on the ground that a prosecutor in the office of Thomas E. Dewey, then the District Attorney, had deliberately used perjured testimony and had suppressed evidence that might have proved Mr. Zimmerman's innocence. After being freed, Mr. Zimmerman filed successive lawsuits against the state for compensation but these were blocked by laws granting the state immunity from suits based on prosecutorial actions, the 11th Amendment provision restricting citizen suits against the government and other legal barriers.

A private bill granting permission for Mr. Zimmerman to sue was passed by the Legislature and signed by Gov. Hugh L. Carey in 1981, clearing the way for his successful lawsuit.

Mr. Zimmerman, who was married soon after his release from prison, is survived by his wife, Ruth.

LAST night in Sing Sing's Death House three slum-reared youths were executed for the murder of Detective Michael J. Foley in an abortive tea room stickup at 144 Second Avenue on April 10, 1937.

They were Arthur (Hutch) Friedman, twenty-two; 206 Madison Street; Dominick Guariglia, nineteen, 219 Henry Street, and Joseph Harvey O'Laughlin, twenty-four, 255 East Broadway.

OSSINING, Jan. 27--"Good-by."

This is Hutch Friedman, at 11:01 1/2 last night, signing off on the whole world. He comes into the Execution Chamber walking--staggering--sideways. His eyes are closed as he comes through the little door to the left and is led to The Chair.

Principal Keeper John J. Sheehy and two burly guards strap the doomed man into place, speedily and efficiently. The cathode on the close-shaven head. The half-mask on the face. The straps around the sunken chest and scrawny arms. The electrode on the right leg. It takes only a few seconds.

Again the whirring sound, and the whole body jerks upward. The hands move again. The mouth opens wider. A curl of smoke flickers from the head and right foot. Along the sidewall, Rabbi Jacob Katz reads a Hebrew prayer. At the entrance, Warden Lewis E. Lawes stands disconsolate; his eyes are closed. The Warden never watches an execution. He is opposed to capital punishment.

Time to think about Hutch, for his brief and sorrowful history is closing. They blame all his trouble on the truck that ran him down when he was seven, injuring his feet, legs, jaw, and skull. His mother said "he was always a problem" after the accident. He had six arrests since 1931, did time in Hawthorne School and the City Reformatory.

The family was poor. Hutch grew up on Claremont Parkway, little Bronx counterpart of Manhattan's cesspool of crime, the lower East Side, whence the Friedmans moved a few years ago. "He spent most of his time drifting around the streets where he lived," the probation report said.

Yes, and "drifting around" he met other boys who were drifting. Boys who had a creed that went like this: "We have nothing. No breaks. No money. No chance. No good jobs. What we want we'll take. We'll rob and steal." The creed of countless thousands growing up in the slums.

Liquor, and later marihuana helped Hutch Friedman expand his philosophy. The night Mike Foley--he had a wife and child--was shot Hutch came into a tea room wildly screaming, "This is a stickup! Don't move!" He had a gun, but when the shooting began he rushed into the kitchen and threw it into the flour barrel. He was stiff with fright.

Not fright, but astonishment now mars his drawn face as the third whirring sound fills the room and the body grows taut.

The guard rips open the white shirt and wipes the chest with a towel. Doctors Charles C. Sweet and Kenneth McCracken apply stethoscopes, and Doctor Sweet says:

"This man is dead."

It's 11:04, and Hutch's limp form is wheeled away. Dominick Guariglia is next.

Dominick, nineteen, was tougher than Hutch in his last day on earth. He ate all of his last meal--chicken, string beans, tomato salad, ice cream. In the pre-execution chamber during the evening he listened attentively while Warden Lawes' victrola droned out the three records he requested--"In My Mother's Eyes," "There's a Gold Mine in the Sky" and "It's a Sin to Tell a Lie."

He comes into the chamber a husky boy, barrel-chested, tough-looking, but pale. Father McCaffrey is at his side, reading, "The Lord is my shepherd..."

It is just short of 11:06 and Dominick is strapped into place. He stares a moment at the people who came to see him die (seven newspapermen on business; the other men just for the hell of it) and you hear the dynamo's sickly whir. Over against the wall a man ducks his head into the sink and retches violently, but he is erect in time to see the rest.

The rest is quick. Executioner Robert Elliot, earning $450 this night, times his heavy voltage blows precisely. The life he's taking never counted much. Just another mugg.

Dominick had low mentality. In the trial last April-March, his attorney called him "A stupid boy, a moron, a nitwit." In the clemency hearing before Governor Lehman January 11, another attorney pointed out Dominick had shined shoes, ran errands, blocked hats, etc. He was industrious. Jacob J. Rosenblum, the prosecutor took this up at the trial. He said when Dominick wanted to he went out and shined shoes, ran errands, blocked hats, etc., and "when he wanted to rob and steal he went out and robbed and stole."

No one knows how this kid got hooked into the Foley killing. He didn't belong with those other muggs. He hadn't graduated into the murder class. He said he was dragged along and forced to carry the guns up Second Avenue for the others. He was the arsenal. He said he refused to do it, but, that Little Benny Ertel (indicted in the crime but not tried yet) told him "Come on, you little--what are you scared of?"

So he carried the guns, handed them to O'Laughlin, Ertel and Friedman and--unarmed--followed Friedman into the tea room, and he, too, cowered in the back while O'Laughlin and Little Benny shot it out with Foley and his partner John R. Gallagher, who happened to be there when the boys arrived.

There's the third whir, and the lights dim a little. The smoke curls up beyond Dominick's ears, his right leg is seared and his eyes pop and his mouth is wide open. The medicos again, and Dr. Sweet hardly audible:

"This man is dead."

It's 11:09 and the boy is wheeled into the autopsy room; it's the turn of Joseph Harvey O'Laughlin, whom everyone called Harvey. He's a defiant youth. He is brought in and as he reaches The Chair he steps forward and says:

"Can I have a word? I'm glad the other boys got a break. Probably if I had a name like Cohen or a longer nose I would have got a break. Let's go, Bob." (Robert is the first name of Father McCaffrey.)

Harvey is strapped in--it's 11:11 now--and you hear him say:

"It's powerful, huh?"

He says this either before or just as the first charge is on the way through him.

It's hard to tell when he says it, because at the same time the man in the row ahead sinks to the floor and makes the sign of the cross. This man is weeping bitterly. (Later he tells the Brooklyn dentist who sat next to him that years ago thugs killed his father, a policeman, and he has always wanted to see a tough guy burn. Harvey was too much for him. He's still bawling in the prison-wagon drive back to the front entrance.)

Harvey is still in The Chair, and it's time to think about him, as you dimly hear Father McCaffrey, the good Chaplain, reading the Twenty-third Psalm.

Harvey is twenty-four. He's the one accused of firing the fatal shots. He had an unfortunate childhood. His father was a drunk. Mrs. Ellen O'Laughlin kicked him out long years ago when she was bearing her seventh child and she went to work. She worked fourteen years, mostly a laundress. At seven, Harvey was assigned to the Bellevue Hospital boat in the East River. At thirteen, he started going to Public School 147 and four years later he quit and went to work. Never earned much.

In March, 1935, he eloped with Irene Weiss, a Jewish girl from the East Side. They broke up the next year--parental objections. They had a son, Robert, three now.

Harvey's mother said that a week before the Foley killing he was talking about raising some money so he could take Irene and the baby out to Long Island and set up house again.

He was desperate, his mother said. The year before he had lost his $53 a month job as a WPA laborer. He was up against it. Thus did he come to sit in the board of strategy the night--April 9, 1937--when the boys assembled in Tobias Hanover's candy store at 218 East Broadway and plotted a crime.

Maybe so, but the probation report said:

"Home environment marred by family disintegration, he elected to associate with the criminal element that frequent the street corners and questionable resorts of the lower East Side...constantly under police surveillance."

It's simple to understand. Harvey had to have some money, a lot of money, and he went out to get it with a gun. A lot of boys do it that way. Only a few weeks before the fatal stick-up (in which Harvey was shot twice) some other boys had "taken" the joint at 144 Second Avenue for $3,500. Easy money.

And easy dying. The deft Mr. Elliot is superb tonight. On the second deathly whir you seem to hear Harvey say "Ugh" and you certainly hear the awful internal body sound of all who die in that grisly looking chair, and the hands turn and the right foot turns and sears badly and the warden stands with bowed head.

You hardly notice the solemn medical men, but you're leaning forward and at 11:14 you catch Dr. Sweet again:

"This man is dead."

Total elapsed time; thirteen minutes.

One spring night in 1937, soon after Isidore Zimmerman of New York City had received a scholarship to attend Columbia University, his mother told him that the police wanted to talk to him. He reported to the local precinct and then quickly found himself in jail. One year later, Zimmerman and four other youths were sentenced to death for the first-degree murder of a police detective.

All along, Zimmerman insisted that he was innocent. Then just two hours before Zimmerman was to be executed in Sing Sing's electric chair, Governor Herbert Lehman commuted his death sentence. Zimmerman went on to become a celebrated jailhouse lawyer, and in 1962, after New York State's highest court ruled that he had been the victim of perjured testimony, he was set free. Total time served: nearly 25 years.

Since the prosecutor had known that the testimony was false, Zimmerman believed that New York should compensate him for wrongful imprisonment. The doctrine of sovereign immunity bars most such suits against a state, so Zimmerman pressed the New York legislature to pass a special law allowing him to sue. Three times the legislators voted the bill, and three times then Governor Nelson Rockefeller vetoed it. Last week Governor Hugh Carey signed the fourth bill. Lawyers on both sides agree that Zimmerman is likely to win his case. The only question is whether he will be awarded as much as the $10 million he is seeking. Whatever he gets, the money will be welcome to Zimmerman, 63, who now works as a doorman at a Manhattan apartment house.

Five Mothers

In day coaches on a train from New York City to Albany last week rode five despairing, middle-aged women put aboard by a noisy, demonstrative crowd of friends. In a parlor car on the same train, rode New York's bald, kindly Governor Herbert Lehman, glad to be unnoticed. At his office in Albany, some hours later, he met them face to face. For five hours Mesdames Fanny Zimmerman, Yetta Friedman, Ellen O'Loughlin, Yetta Chaleff, Mary Guariglia sat before him silent and tearless (by advice of counsel). For five hours he had to face them while lawyers—talking of poverty, slum life, marijuana, liquor—urged him to commute the sentences of the five women's five sons, aged 19 to 27, who were doomed to die January 26 for committing murder in the holdup of a Manhattan gambling house.* When Governor Lehman had heard all, he solemnly shook the mothers' hands, took a last look into their five anxious faces (see cut), promised to ponder his decision.

This gruesome ordeal had its effect. That very day Assemblyman Edgar F. Moran introduced in the Legislature an amendment to New York's Constitution to let the Governor share his most harrowing responsibility, by setting up a Board of Pardons. Today 16 States have Pardon Boards. But in most States, Governors, though they may rely on other officials to make factual investigations and recommendations, must exercise the awful power of pardoning and commuting sentences alone.

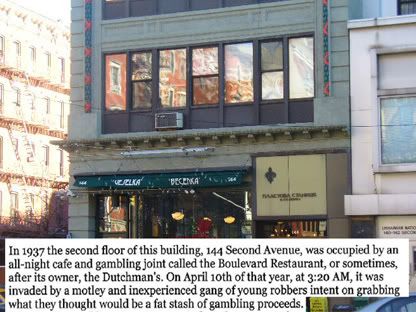

In 1937 the second floor of this building, 144 Second Avenue, was occupied by an all-night cafe and gambling joint called the Boulevard Restaurant, or sometimes, after its owner, the Dutchman's. On April 10th of that year, at 3:20 AM, it was invaded by a motley and inexperienced gang of young robbers intent on grabbing what they thought would be a fat stash of gambling proceeds. The optimism of the greenhorn robbers was unwarranted: at the moment they chose to take the place, two plainclothes policemen, Detective Michael Foley and Detective John R. Gallagher, were inside enjoying a coffee break with the Dutchman.

Leading the charge up the stairs was 20 year old Arthur "Hutch" Friedman armed with a borrowed .32 pistol. Close on his heels were 17 year olds Dominick Guariglia (unarmed); Benjamin "Little Benny" Ertel (with a .38 that evidently did not work); and 22 year old Joseph Harvey O'Laughlin (with a .38 that did). Left behind on the sidewalk outside, with uncertain degrees of participation in the crime, were Philip "Sonny" Chaleff and Isidore "Little Chemey" Perlmutter.

As Guariglia barked, "This is a stick up! Everybody out!" he and Friedman began to herd patrons toward the kitchen in the back. O'Laughlin approached the Dutchman and his two friends: "All right, you bastards," he shouted, "in back with the rest!" Instead, the two lawmen went for their guns, and in a wild, quick flurry of shooting, Foley was fatally wounded. What started out almost as a lark had become a capital crime.

The case of the these novice gangsters, dubbed "The East Side Boys" by the press because they all came from the Lower East Side neighborhood around East Broadway and Clinton Street, was briefly notorious. Guariglia, O'Laughlin, Friedman, Chaleff, and a fifth defendant (Isidore "Beansy" Zimmerman, who was not present at the incident but was accused of supplying one of the .38 pistols), were found guilty of murder in the first degree on April 14, 1938.

On January 26, 1939, Guariglia, O'Laughlin, and Friedman were executed at Sing Sing. Chaleff and Zimmerman's sentences were commuted to life imprisonment. Chaleff died in prison in 1954.

Two of the "East Side boys" named in the indictment, Ertel and Perlmutter, went on the lam and were not tried with the others. Ertel was apprehended in Washington D.C. in 1938, and tried and executed in 1940 for his part in the robbery. Perlmutter died in 1956, never having been brought to justice.

Isidore Zimmerman's case is interesting. He was never accused of direct participation in the robbery, and all parties admitted he was nowhere near the restaurant that night. He was indicted, rather, for supplying one of the pistols, a charge he denied throughout his twenty-four years in prison. He was released in 1962 when it was proved that one of the witnesses against him in his original trial had lied. The state declined to retry him, and Zimmerman, after a very long absence, returned home.

21 years later the New York Court of Claims awarded him $1,000,000 for his ordeal. He died 4 months later, after having spent 24 of his 66 years in prison. Zimmerman had his death penalty commuted to a life term just hours before he was scheduled to be electrocuted (he willingly sought execution because of the intense psychological torture of being on death row)