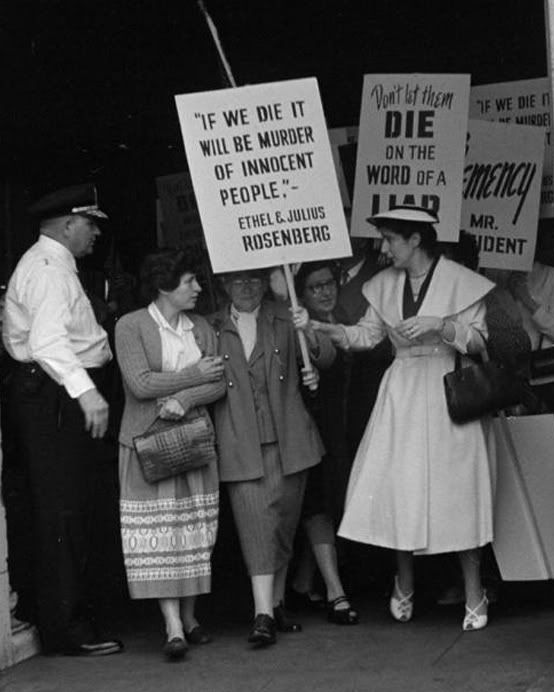

No matter what your feelings might be about the Rosenberg case you can't help but tip your hat to the courage and conviction of the Almans.

from the Saratogian of 9/22/2002Attorney revisits traitor case of Rosenbergs/Sobell at Skidmore

In 1953, Americans Ethel and Julius Rosenberg and Morton Sobell were convicted of conspiring to steal classified information about the atomic bomb on behalf of the Soviet Union. The Rosenbergs were sentenced to death, and Sobell was sentenced to 30 years in prison. Sunday, September 22, 2002, By MAE G. BANNER

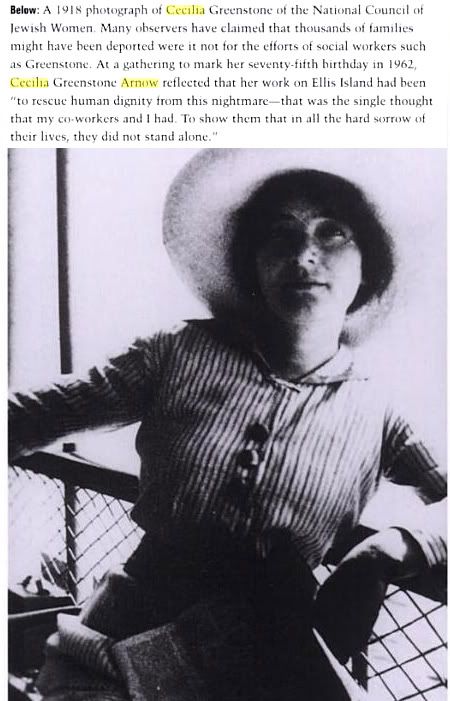

From the outset of the case, many believed that a gross miscarriage of justice was being done. One of those who questioned the trial and sentence was Dr. Emily Arnow Alman, a professor emerita and former chairwoman of the Sociology Department at Douglass College, Rutgers University. Dr. Alman also is an attorney who has received many honors for her service to clients and to the field of matrimonial law.

Now a resident of Ballston Spa, Dr. Alman will give a talk, ''The Case against Julius and Ethel Rosenberg and Morton Sobell: Was Justice Done?'' at 7:30 p.m. Monday, Sept. 23, in Wilson Chapel on the Skidmore College campus. The talk is free and open to the public.

Dr. Alman will describe the social and political context of the time, 1950-53, in which the Rosenberg-Sobell case arose. Also, she will present evidence to support her conclusion, arrived at through decades of study, that the defendants were wrongly convicted.

In 1951, Dr. Alman became interested and involved in the Rosenberg-Sobell case. After reading the trial transcript, she was convinced that a gross miscarriage of justice had occurred. She helped to form the National Committee to Secure Justice in the case. The committee's goals were to obtain a new trial for the defendants and/or clemency for the Rosenbergs.

New evidence surfaced, including a written confession by David Greenglass, the prosecution's chief witness, that he had agreed to testify to matters he knew nothing about first-hand, but that had been described to him by the FBI.

The committee published 10,000 copies of the verbatim trial transcript and sent copies to editors, government officials, scientists, members of Congress and prominent persons. Similar committees arose in major cities around the country, and their efforts culminated in a vigil at the White House. There was also an outpouring of support from around the world. The New York Times estimated that at least 3 million Americans eventually petitioned the White House for clemency for the Rosenbergs.

In 1956, three years after the execution of the couple, Dr. Alman and her husband David were called to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee, where they defended the right of Americans to criticize prosecutorial and judicial actions that led to miscarriages of justice.

While on sabbatical leave from Rutgers in 1978, Dr. Alman used the Freedom of Information Act and other sources to obtain many definitive documents bearing on the case, including a pre-trial assurance by Federal Judge Irving Kaufman to the Department of Justice that he intended to sentence Julius Rosenberg to death. Other documents came from the Atomic Energy Commission, the State Department and the Department of Justice.

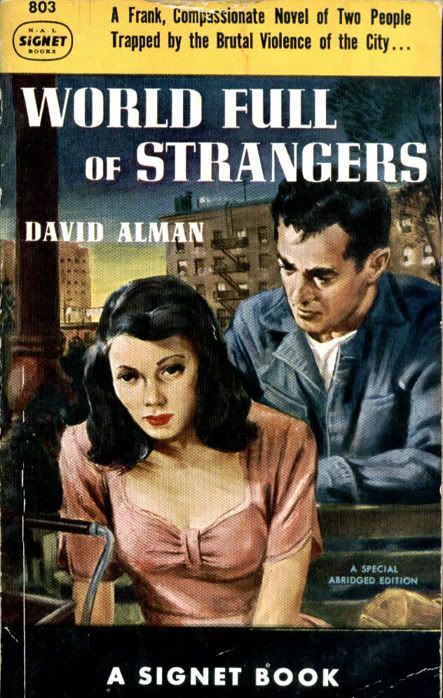

Dr. Alman and her husband are now completing a book on the case that will carry the first full account of the activities of the Committee to Secure Justice and of the campaign for a new trial and clemency that they spearheaded. The book will examine the case in light of David Greenglass's televised confession in December, 2001, that he had committed perjury at the Rosenberg-Sobell trial at the instruction of the prosecution.

The Skidmore lecture is co-sponsored by the Saratoga Springs chapter of Hadassah, which is the largest Jewish women's Zionist organization in the U.S.

from Emily's 2004 obituary

Emily Arnow Alman BALLSTON SPA -- Emily Arnow Alman of Ballston Spa died on March 18, 2004, at the age of 82. Dr. Alman was a sociologist and attorney.At her retirement from law, she was honored with a plaque by the Middlesex County Bar Association of New Jersey that read in part, 'The fact that you often faced overwhelming odds could not quench your indomitable spirit.' Dr. Alman was committed to advancing the causes of battered women, the poor and the rights of children in broken homes to have access to both their parents and grandparents. Dr. Alman received her B.A. at Hunter College in 1945 and her M.A. and Ph.D. at the New School For Social Research in 1963.She received her law degree at Rutgers University Law School in 1977.She taught sociology at Rutgers University's Douglas College from 1960 to 1986 and served as chairperson of the Department of Sociology for eight years.Her chief interests in sociology and law were family law, bias law and public policy law and interactions between social agencies and institutions and various population groups.

Dr. Alman's creative works include 'Ride the Long Night,' a novel (McMillan, 1963), and 'The Ninety-First Day,' a semi-documentary film on mental illness and shortcomings in institutional treatment (1963). 'We Were There,' a book in progress at the time of her death and co-authored with her husband, is based on government documents.

Dr. Alman was persuaded by the trial record to become one of the founders of a committee in 1951, the National Committee to Secure Justice in the Rosenberg-Sobell Case, to secure a new trial or clemency for the Rosenbergs and reduction of Morton Sobell's 30-year sentence. Dr. Alman was also a chairperson of the Concerned Citizens of East Brunswick, N.J., from 1970-78, which was instrumental in causing the New Jersey Turnpike to erect noise abatement berms along portions of the turnpike.She was also a member of the American and New Jersey bar associations and a number of professional associations and organizations for the protection of battered women.

Dr. Alman won first prize at the American Film Festival in 1964 for 'The Ninety-First Day' and the Appleton Award for dedicated service to the legal community.A short biography of her appears in Who's Who in American Women. Prior to becoming a sociologist and lawyer, Dr. Alman was a New York City probation officer.From 1957 to 1970, she and her husband and children were farmers in Englishtown, N.J. In 1972, Dr. Alman was an Independent candidate for mayor of East Brunswick, N.J. She is survived by her husband, David, whom she met at the age of 13 and married in 1940 at the age of 18 and with whom she celebrated every day of her life.