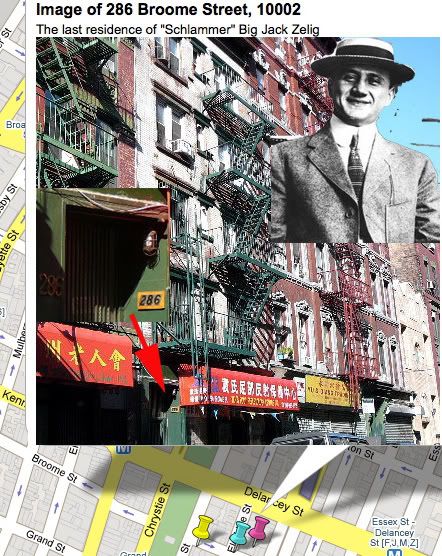

from Rose Author of The Starker: Big Jack Zelig, the Becker-Rosenthal Case, and the Advent of the Jewish Gangster,

on the left is Whitey at the trial

On December 2, 1911, a Five Pointer named 'Julie' Morrell crashed a ball thrown by the Boys of the Avenue. Zelig shot him full of holes and hurled him into the street. The following February Morrell's partner Frank Renesi was found with his head blown off. When Jonesy the Wop, a friend of both slain men, cursed Zelig as a 'Jew bastard' and attacked him in a restaurant with a knife, the Jewish gangster disarmed him and sliced up his face.

The violence peaked in early June 1912, when Zelig, Lefty Louis, and Whitey Lewis brawled with Tricker and a bevy of Five Pointers at a Chinatown dive, and all were arrested. When Zelig left the courthouse afterward, he was shot in the head by a gunman named Charles Torti, a known associate of Jack Sirocco. While surgeons operated on him, his boys nearly killed Tricker in a drive-by shooting.

Upon his discharge from the hospital, a weakened Zelig was sent to the Tombs prison to await bail. Once it was posted, he left for Hot Springs to complete his recovery. His departure took place days before New York witnessed a murder whose repercussions would send five men to Sing Sing's electric chair. This tragedy and ensuing miscarriage of justice would go down in history as the Becker-Rosenthal affair.

In July 1912 a waning gambler named Herman Rosenthal declared to the press and District Attorney's office that Police Lieutenant Charles Becker, who headed one of the NYPD's elite Strong Arm Squads, had been a silent partner in his gambling house for months. When Becker's superiors forced him to shut the place down, an enraged Rosenthal retaliated by exposing the policeman as a venal wolf in a cop's uniform. His allegations made the front pages of the daily papers and shocked New Yorkers with lurid tales of police-gambler collusion.

Becker and the NYPD weren't the only ones burned by the heat that ensued. Told that he needed corroborative witnesses before his case could be taken to the grand jury, Rosenthal named fellow gamblers who wanted no part of an investigation. Threats against his life were heard in poker rooms and stuss houses everywhere. Therefore, when Rosenthal was shot to death outside the Metropole Hotel on July 16, popular opinion was divided on who ordered the hit: some pointed the finger at Becker while others blamed the victim's former colleagues.

The latter theory appeared to be correct when three gamblers named Bald Jack Rose, Louis 'Bridgey' Webber, and Harry Vallon were arrested. Rose, who was also a graft collector and stool pigeon for Lieutenant Becker, admitted to hiring the shooters. But he stressed to District Attorney Whitman that he and his two confederates had acted as agents of Becker, who threatened them with jail time or worse if they did not silence Rosenthal forever.

Although all three were known enemies of the victim, the politically ambitious Whitman foresaw more glory in prosecuting a corrupt cop for murder instead of three scheming lowlifes. He hurried them before the grand jury, which promptly indicted Becker for murder, and granted them immunity in exchange for their testimony.

One by one, the hired guns were picked up. They were none other than Lefty Louis, Whitey Lewis, Gyp the Blood, and Dago Frank. With their leader out of town, they had somehow been persuaded to bend the rule about avoiding gamblers' feuds. Jack Rose would say that fear of Becker made them acquiesce, but Benny Fein met with Zelig in Boston and filled him in on what had really happened.

On the night of July 15, Rose had met with the quartet at Bridgey Webber's poker place, plied them with liquor and cocaine, and convinced them to beat up Rosenthal. After the target was located at the Metropole, the original agreement received a lethal modification. Harry Vallon, seething with hate, fired at Rosenthal first, and a coked-out Louis and Gyp mechanically followed suit. Whitey missed fire, and Dago Frank was not even present, having decided at the last minute to go home.

Zelig was furious. He knew that Lieutenant Becker had nothing to do with the crime. Jack Rose tried to hire him to kill Rosenthal in April, citing a long-standing personal feud. Zelig refused, but Rose did not give up. When the gangster was jailed in May on a bogus gun-carrying charge, the bald gambler offered to use his influence with Becker to get the charge dropped. All he wanted in exchange was for Zelig to order his men to rub Rosenthal out. Again he was rebuffed. Rose tried one more time, visiting Zelig in late June while he was in the Tombs prison awaiting bail for his role in the Chinatown brawl. Temper soured by pain from his bullet wound, the gang leader erupted and sent him running. Jack Rose made no further approaches- until Zelig was out of town and unable to interfere.

Now Herman Rosenthal was dead, and Becker and the gunmen were facing the electric chair. Zelig knew that he could not save his friends, as there had been too many witnesses to the shooting, but he could make sure that they had company on Death Row. Zelig notified Becker's defense team that he had exculpatory evidence to offer. He was no lover of cops, but he could not sit and watch an innocent man suffer the death penalty because Jack Rose successfully conned an ambitious district attorney. Shoenfeld's 'man of principle' was prepared to act.

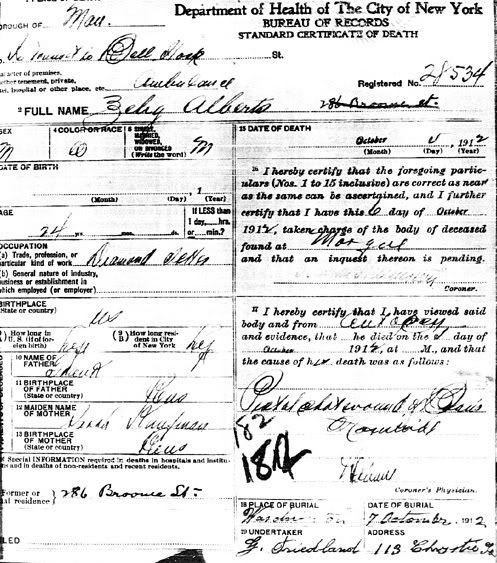

Zelig would never take the stand. On the rainy evening of October 5, 1912, two days before Becker's trial was due to commence, the gangster left Segal's and went to a nearby barbershop for a shave. Then he boarded a Second Avenue streetcar to go home. As the trolley neared Thirteenth Street, Zelig was shot in the head from behind by 'Red' Phil Davidson, a pimp who poisoned horses as a sideline. Davidson, who was arrested without difficulty, said that he had killed Zelig for beating him and stealing his money -a sum he fixed as different times as $400 and $18.

No one believed him. Davidson was a noted coward and an easy tool for those with a stronger will. It was whispered that certain members of New York's political machine did not want Zelig to testify, worried that if Becker went free, Rose and his cohorts might bargain for their lives by handing some bigger fish to Whitman on a platter. Because the gang leader was too powerful to be silenced via threats, he was assassinated. His evidence died with him, and Lieutenant Charles Becker was convicted of murder and executed in Sing Sing's electric chair on July 30, 1915. Lefty Louis, Whitey Lewis, Gyp the Blood, and even Dago Frank, who had not even been present at Rosenthal's murder, were electrocuted in April 1914.

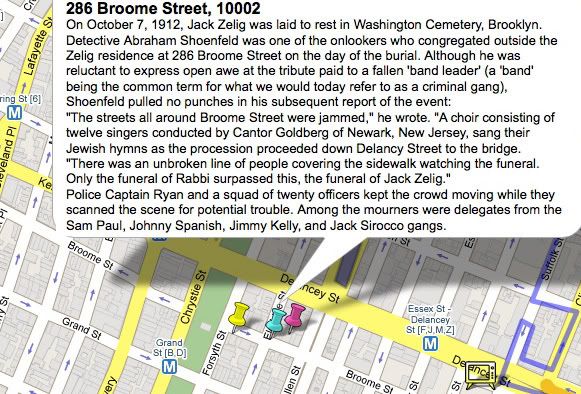

The funeral of Zelig Lefkowitz, alias Big Jack Zelig, was attended by thousands. His supporters hired a fleet of cars to transport his remains to Washington Cemetery in Brooklyn. Talmud Torah children and a choir conducted by Cantor Goldberg of the Shaare Shamayim synagogue accompanied the coffin. Benny Fein and other tough gangsters joined Zelig's family in shedding tears. The conservative Jewish press decried the dead man as a murderer and reprobate, but the residents of the Jewish quarter had benefited from the gangster's protection, and their grief was genuine. Many knew that he died because he intended to save a man's life.

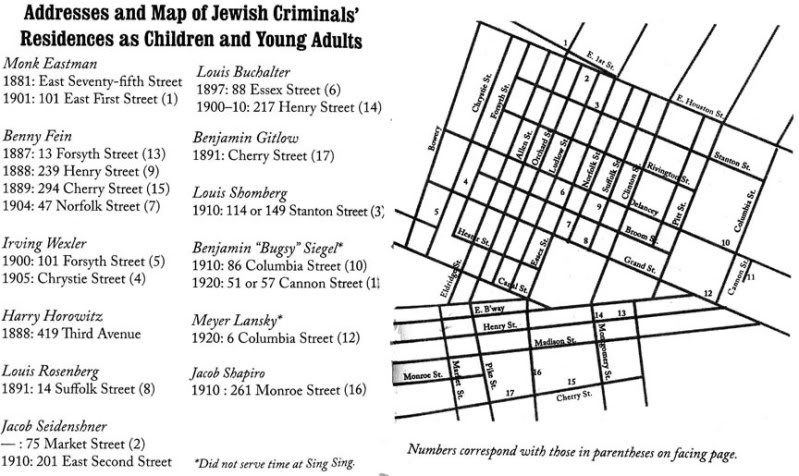

Shortly after Zelig's death, Abe Shoenfeld wrote, "Jack Zelig is as dead as a door nail. Men before him - like Kid Twist, Monk Eastman, and others - were as pygmies to a giant. With the passing of Zelig, one of the most 'nerviest', strongest, and best men of his kind left us."

Interesting Facts

* Zelig’s sister-in-law, Amelia Lewis, became a celebrated attorney who helped reshape the American juvenile justice system. In 1967, thanks to a case that she argued, the United States Supreme Court ruled that juveniles charged with criminal offenses were entitled to the same procedural protections in juvenile courts that adults had in the criminal courts.

* Zelig’s great-grand-nephew, Jan Lefkowitz, portrays him in a series of webisodes titled Our Gotham. www.monk1903.com