from the nytimes of 8/14/11

Arrested 1900

I did a search to see if any of these came from the "crime laden" Fourth Ward.

Only possible hit was John Alexander, who in 1920 was living in a flophouse at 100 Bowery. His ancestry was from Russia.

Showing posts with label bowery. Show all posts

Showing posts with label bowery. Show all posts

Tuesday, August 16, 2011

Wednesday, March 24, 2010

Tim Sullivan: King Of The Bowery 2

Since Tim always made sure everyone had shoes in his Bowery ward I thought this song might fit. The singer, Maria Dunn is deserving of a wider audience

the lyrics

I walked as a soldier, they carried me home

Then I walked to the factory, they gave me the dole

So I read 'til my head spinned to know of this world

That I shared with a pretty young girl

I came across the water from County Tyrone

And I took my first steps at the century's turn

I walked as a schoolboy, no shoes to my name

Learning my pleasure and poverty's pride my shame

I walked as a soldier, they carried me home

My chest with a bullet and a wallet now torn

Every snapshot was pierced, faces young and serene

Just the friends of a soldier in 1917

It's the shoes of a man tell a life the way words never can

I walked with my Kate as the twenties roared on

Now here was a woman both canny and strong

A fine crop of children the blessings she bore

And we taught them the riches of even the poor

Yes I walked with the unions to ring in some change

That our labour be valued and ours a fair wage

And I walked with my ballot to vote out the means

And I stood with the people on Glasgow Green

Now I walk as an old man, they carry me home

My mind sometimes faulty, belaboured and slow

But I still tell my stories, songs and my dreams

To those with the patience for old memories

Tim Sullivan: King Of The Bowery

Tim's Funeral

I heard Richard Welch speak about his excellent book, King of the Bowery: Big Tim Sullivan, Tammany Hall, and New York City from the Gilded Age to the Progressive Era at the Tenement Museum. One of the strong points he makes is that in studying LES history not enough research and interest has been devoted to this crucial pre 1900 and early 1900 time.

Tim Sullivan's bio, an excerpt from wikipedia

I heard Richard Welch speak about his excellent book, King of the Bowery: Big Tim Sullivan, Tammany Hall, and New York City from the Gilded Age to the Progressive Era at the Tenement Museum. One of the strong points he makes is that in studying LES history not enough research and interest has been devoted to this crucial pre 1900 and early 1900 time.

Tim Sullivan's bio, an excerpt from wikipedia

Timothy Daniel Sullivan (July 23, 1862 – August 31, 1913) was a New York politician who controlled Manhattan's Bowery and Lower East Side districts as a prominent figure within Tammany Hall. He was euphemistically known as "Dry Dollar", as the "Big Feller", and, later, as "Big Tim" (because of his large stature). During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, he controlled much of the city's criminal activities between 14th Street and the Battery in New York City. He is credited as being one of the earliest ward representatives to use his position to enable the activities of criminal street gangs.

Born to Daniel O. Sullivan and Catherine Connelly (or Conley), immigrants from Kenmare, County Kerry, Ireland in the slum of Five Points. Daniel Sullivan, a Union veteran of the American Civil War, died of Typhus in October 1867 at the age of thirty-six leaving his wife to care for four children. Catherine remarried in 1870 to an immigrant, alcoholic laborer named Lawrence Mulligan, eventually having six more children.

At the age of eight, Sullivan began shining shoes and selling newspapers on Park Row in lower Manhattan. By his mid-twenties, Sullivan was the part or full owner of six saloons which was the career of choice for an aspiring politician. Sullivan soon caught the attention of local politicians, notably Thomas "Fatty" Walsh, a prominent Tammany Hall ward leader. In 1886, at the age of twenty-three, he was elected to the state Assembly in the old Third District.

That year, Sullivan had married Helen (née Fitzgerald). Gradually, he began building one of the most powerful political machines which controlled virtually all jobs and vice below 14th Street in Manhattan. His base of operation was his headquarters at 207 Bowery. By 1892, Tammany Hall leader Richard Croker appointed Sullivan leader of his assembly district of the Lower East Side.

Sullivan briefly served one term in the U.S. Congress from March 4, 1903 until his resignation on July 27, 1906. According to some accounts, Sullivan was dissatisfied with the graft and anonymity of political life in the Capitol prompting his resignation while remarking that "In NY, we use Congressmen for hitchin' posts." He was later elected to Congress in 1912, but due to ill health, never took his seat. (See, A.F. Harlow, Old Bowery Days). Instead, Big Tim chose to remain a state senator for most of his political career serving two terms in the New York State Senate from 1894-1903 and again from 1909-1912.

It could be said that Sullivan was one of the earliest political reformers and was aligned with women's rights activist Frances Perkins and sponsored legislation limiting the maximum number of hours women were forced to work; improving the conditions of stable and delivery horses and of course, gun control legislation euphemistically termed the Sullivan Law.

Despite his political and criminal activities, Sullivan was undeniably a successful businessman involved in real estate, theatrical ventures (at one point partnering with Marcus Loew), boxing and horseracing.

Along with various other Sullivans (Big Tim also branched out into popular amusement venues such as Dreamland in Coney Island, where he installed a distant relative, Dennis, as the political leader. Sullivan, whose control extended to illegal prizefights through the National Athletic Club, influenced the New York State Legislature to legalize boxing in 1896 before ring deaths and other scandals caused the law's repeal four years later.

Among other laws he helped pass was the Sullivan Act, a state law that required a permit to carry or own a concealed weapon, which eventually became law on May 29, 1911. However, with many residents unable to afford the $3 registration fee issued by the corrupt New York Police Department and guaranteed his bodyguards could be legally armed while using the law against their political opponents.

He was extremely popular among his constituents. In the hot summer months, tenement dwellers would be feted to steamboat excursions and picnics to College Point in Queens or New Jersey. In the winter months, the Sullivan machine doled out food, coal and clothing to his constituents. On the anniversary of his mother's birthday, February 6, Sullivan dispensed shoes to needy tenement dwellers. The annual Christmas Dinners were a particularly notable event covered in all of the city papers. Although he had a loyal following, his involvement in organized crime and political protection of street gangs and vice districts would remain a source of controversy throughout his career.

Labels:

big tim sullivan,

bowery,

irish,

tammany hall

Saturday, March 20, 2010

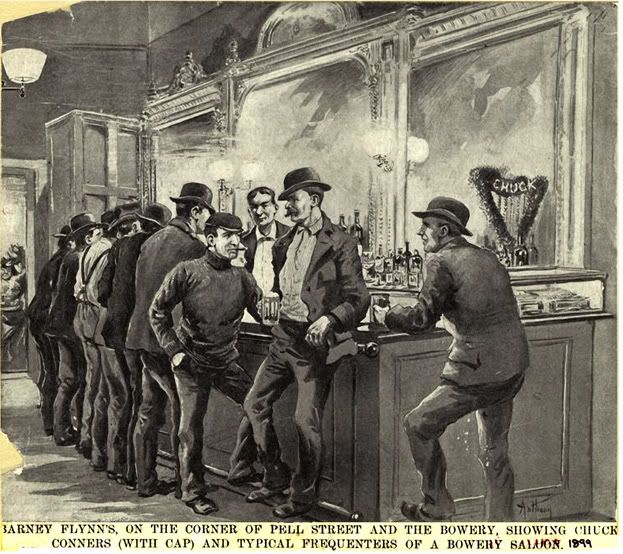

Chuck Connors: The Mayor of Chinatown Dies, 1913

Chuck Connors 2

Chuck article states that Chuck lived at 6 Doyers Street

Chuck article states that Chuck lived at 6 Doyers Street

Thursday, March 18, 2010

Frederick Fleck In The News

Frederick Fleck

Fleck was mentioned previously in an article about 104 Bowery

Not only did he own places on the Manhattan Bowery, he also did on the Coney Island Bowery.

About the Coney Island Bowery from the virtual dime museum

Fleck was mentioned previously in an article about 104 Bowery

Not only did he own places on the Manhattan Bowery, he also did on the Coney Island Bowery.

About the Coney Island Bowery from the virtual dime museum

The Bowery at Coney Island was a plank street laid out in 1882 by George C. Tilyou, one of the pioneer developers of Coney Island as a summer resort and amusement complex. It was named for the Bowery, the oldest street in Manhattan - which by the 1880s had a reputation as a rather shady place lined with cheap amusements, saloons and flophouses.

Originally a little alleyway between larger streets running down to the sea, the Coney Island Bowery was enhanced by the wooden planking and gave it a new importance. Tilyou's idea was to give people a quick route past the amusement places which would lead them straight to the Tilyous' Surf Theater.

Many dance halls, saloons and cheap stands which sprouted up on either side, hoping to benefit from the crowds of pedestrians using the walk. The Bowery soon became the center of Coney Island amusement, often photographed and the subject of penny postcards.

Monday, March 15, 2010

The Last Greek At 104 Bowery

an excerpt from the nytimes of 3/14/10

On the Bow’ry, By DAN BARRY

OPEN the door to a small hotel on the Bowery.

A small hotel, catering to Asian tourists, that used to be a flophouse that used to be a restaurant. That used to be a raucous music hall owned by a Tammany lackey called Alderman Fleck, whose come-hither dancers were known for their capacious thirsts. That used to be a Yiddish theater, and an Italian theater, and a theater where the melodramatic travails of blind girls and orphans played out. That used to be a beer hall where a man killed another man for walking in public beside his wife. That used to be a liquor store, and a clothing store, and a hosiery store, whose advertisements suggested that the best way to avoid dangerous colds was “to have undergarments that are really and truly protectors.”

Climb the faintly familiar stairs, sidestepping ghosts, and pay $138 for a room, plus a $20 cash deposit to dissuade guests from pocketing the television remote. Walk down a hushed hall that appears to be free of any other lodger, and enter Room 207. The desk’s broken drawer is tucked behind the bed. Two pairs of plastic slippers face the yellow wall. A curled tube of toothpaste rests on the sink.

Was someone just here? Was it George?

Six years had passed since I was last in this building at 104-106 Bowery. Back then it was a flophouse called the Stevenson Hotel, and I was there to write about its sole remaining tenant, a grizzled holdout named George; toothless, diabetic, not well. He lived in Cubicle 40, about the length and width of a coffin.

All the other tenants, who had paid $5 a night for their cubicles, had moved on or died off, including the man known as the Professor, and Juliano, who used to beat George. The landlord, eager to convert the building into a hotel, a real hotel, had paid some of them to leave. But George had refused, saying the last offer of $75,000 was not enough.

It was as though he belonged to the structure, a human brick, cemented by the mortar of time to the Professor and Alderman Fleck and all the others who gave life to an ancient, ordinary building on the Bowery.

Now the place is the U.S. Pacific Hotel, and George is nowhere to be seen. I dim the lights in my own glorified cubicle, and give in to musings about his whereabouts, and long-ago murders, and the Bowery, where, the old song said, they say such things and they do strange things.

On the Bow’ry. The Bow’ry.

THE building at 104-106 Bowery, between Grand and Hester Streets, has been renovated, reconfigured and all but turned upside down over the generations, always to meet the pecuniary aspirations of the owner of the moment. Planted like a mature oak along an old Indian footpath that became the Bowery, it stands in testament to the essential Gotham truth that change is the only constant.

Its footprint dates at least to the early 1850s, when the Bowery was a strutting commercial strip of butchers, clothiers and amusements, with territorial gangs that never tired of thumping one another. Back then the building included the hosiery shop, which promised “all goods shown cheerfully” — although an argument one night between two store clerks, Wiley and Pettigrew, ended only after Wiley “drew a dark knife and stabbed his antagonist sixteen times,” as The New York Times reported with italicized outrage.

Over the years the Bowery evolved into a raucous boulevard, shadowed by a cinder-showering elevated train track and peopled by swaggering sailors and hard-working mugs, fresh immigrants and lost veterans of the Civil War. The street was exciting, tawdry and more than a little predatory. The con was always on.

By 1879, 104-106 Bowery had become a theater and beer hall, with a bartender named Shaefer who was arrested twice in two weeks for selling beer on Sunday. The adjacent theater, meanwhile, sold sentiment.

During one Christmas Day performance of “Two Orphans,” precisely at the audience-pleasing moment when the blind girl resolves to beg no more, someone shouted “Fire!” A false alarm, it turned out, caused when a cook in the restaurant next door dumped hot ashes onto snow. The crowd returned to rejoice in the blind girl’s triumph.

The theater changed names almost as often as plays: the National, Adler’s, the Columbia, the Roumanian, the Nickelodeon, the Teatro Italiano. In 1896, when it was known as the Liberty, the police arrested two Italian actors for violating the “theatrical law.” He was dressed as a priest, she as a nun.

But the building’s dramas were not relegated solely to the stage. One of its theater proprietors skipped to Paris with $1,800 in receipts, leaving behind a destitute wife, six children and many unpaid actors. One of its upstairs lodgers drowned with about 40 others when an overloaded tugboat, chartered by the Herring Fishing Club, capsized off the Jersey coast.

In 1898, two men were laughing and drinking at a vaudeville performance when a third walked up, drew a revolver and shot one of them in the head. Hundreds scrambled for the exits to cries of “Murder!”

The shooter, Thompson, told the police that he had seen the victim, Morrison, on the street with his wife. “He has ruined my life; broken up my home,” Thompson said, as he gazed at the man groaning on the floor. “It’s a life for a wife.”

And the fires, the many fires. The one in 1898 gutted the building and displaced the families of Jennie Goldstein and Sigmund Figman, while the one in 1900 sent 500 theatergoers fleeing into the Christmas night, prompting a singular Times headline: “Audience Gets Out Without Trouble, but the Performers Were Frightened — Mrs. Fleck Wanted Her Poodle Saved.”

MRS. MABEL FLECK, whose poodle survived, was the wife of the proprietor, one Frederick F. Fleck: city alderman, bail bondsman and self-important member of the court to the Bowery king himself, Timothy D. Sullivan — “Big Tim” — a Tammany Hall leader said to control all votes and vice south of 14th Street.

Alderman Fleck was there whenever Big Tim staged another beery steamboat outing for thousands of loyal Democrats, or another Christmas bacchanal for Flim-Flam Flannigan, Rubber-Nose Dick, Tip-Top Moses and hundreds of other Bowery hangers-on. There to provide bail when some Tammany hacks were charged with enticing barflies at McGurk’s Suicide Hall to vote the Democratic ticket in exchange for a bed, some booze and five bucks.

When Alderman Fleck was not demonstrating his Tammany fealty, he was managing the Manhattan Music Hall, here at 104-106 Bowery, a preferred place for dose in de know.

But the city’s good-government types, the famous goo-goos, hated how the Bowery reveled in its debauchery. In 1901, a reform group called the Committee of Fifteen raided Alderman Fleck’s establishment and charged him with maintaining a disorderly house. He responded by calling the arresting officer “a dirty dog.”

Undercover agents testified to having witnessed immoral acts on stage and off. One reported seeing a woman lying on a table, moaning; when he asked what was wrong, he was told she had just consumed $60 worth of Champagne, and so was feeling bad.

But this was Big Tim’s Bowery. A jury quickly acquitted Fleck, prompting a night of revelry at the music hall. A Times reporter took note:

Monday, January 4, 2010

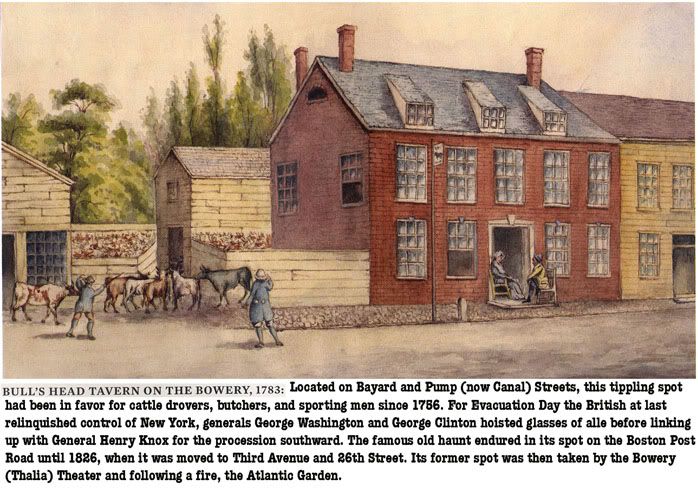

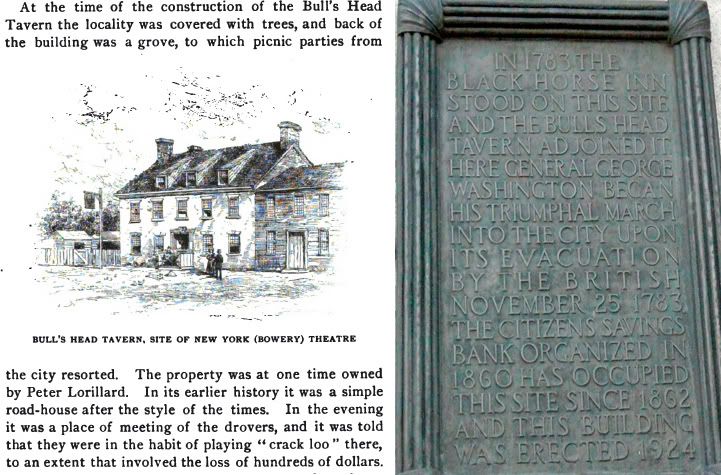

Bull's Head Tavern: Then And Now

from the bowery boys

The Bull's Head Tavern was the gathering-place for farmers, drovers, and merchants in the 18th century, located well outside city boundaries just east of Collect Pond. (At the Bowery, right at the entrance to the Manhattan Bridge.)

It soon became the center of Manhattan's entire meat selling and rendering industry, with the area surrounding the nearby Collect overrun with tanneries and slaughterhouses. As the Bull's Head was also located right on the Boston Post Road (later the Bowery), situated at a crossroads of livestock yards and stables, it became an ideal place for both commerce and carousing.

The Bull's Head was in operation as early as 1755, enjoying business as "the last halting-place for the stages before entering the city."

Within the next few decades, industry enveloped the area, transforming the Bull's Head into a cattle market, with pens adjoining the main building where farmers from the surrounding area herded their best specimens for sale. Inside the tavern became a literal stock market, with transactions, news and gossip being shared over brew and a hot meal. Those who lingered well into the night sometimes played a strange game called crack loo -- often gambling away any profits they might have made earlier in the day. Out in the pen, dog fights and "bear baiting" sometimes occured as entertainment.

As Washington Irving describes, at the Bull's Head he would "hear tales of travelers, watch the coaches and envy the more pretentious country gentlemen in Castor hat, cherry-derry jackets and doeskin breeches."

On November 25, 1783, Evacuation Day, the Bull's Head entered history. As the British fled New York that day, George Washington and his entourage met at the Bull's Head, preparing themselves for their triumphant entry into town. Governor George Clinton and over 800 uniformed troops and townfolk gathered right outside, preparing for the procession.

Henry Astor, the older brother of John Jacob, stepped in as owner of the Bull's Head in 1785. Already an accomplished butcher, Henry served his "celebrated cuts of meats" and often outpriced his own clientele when a particularly choice herd of cattle came travelling by.

Of course, New York was outgrowing its old boundaries by then. By 1813, Collect Pond had been drained and high society eyed the Bowery, sweeping away the filthy stockyards and factories to construct homes, shops and theatres. Moving with the changing times, some civic minded businessmen bought out Astor and moved the Bull's Head somewhere safely outside the city -- this time at 3rd Avenue and 24th Street!

In 1830, this new location fell into the hands young rancher and entrepreneur Daniel Drew, who turned the tavern into a sort of bank, marketplace and social club for local cattlemen, upgrading the establishment and building his own reputation as a saavy financier.

As this time, according to an old history, "various types of men mingled in the bar-rroom of the Bull's Head, from the rough country man to the speculative citizen, butcher and horse-fancier. Plain apple-jack and brandy and water... were the principal liquors passed over the bar. Guests were so numerous that at the first peal of the dinner-bell. it was neccessary to rush for the table or fail miserably." And of course, after hearty meal and vigorous drink, came the gambling, "throwing dice for small stakes."

Drew eventually went on to become a steamboat mogul. The location of the old Bull's Head became the notorious Bowery Theatre. It's uptown location on 24th, of course, caved in to a growing residential neighborhood. However, today there is a new Bull's Head Tavern, at that exact location, that probably smells a lot better than the original.

And not to forget, there was also a Bull's Head Tavern in Staten Island, at Victory Boulevard and Richmond Avenue. Built in 1741, this Bull's Head was a popular destination for British-loving Tories before the days of the Revolutionary War. Before it was destroyed in a fire, "people from all over the country made special trips to the old house, just to see the famous Tory headquarters," according to one old history.

The neighborhood that sprouts around that intersection at Victory and Richmond is named Bulls Head in the old tavern's honor.

Tuesday, December 1, 2009

East Village Dumplings For The Lord

an excerpt from a nytimes article from 9/30/07By ADAM B. ELLICK

AS the sun rises over the imposing blue-green dome of the St. George Ukrainian Catholic Church on East Seventh Street near Third Avenue in the East Village, a small volunteer army of elderly women, many with shawls wrapped around their heads, descend into a nameless luncheonette across the street. The earliest arrivals limp in at 6 in the morning. Once inside, the women scurry around the chromed kitchen, colliding like slow-motion bumper cars.

Every Friday morning for more than three decades, these women have been hand-rolling 2,000 plump potato dumplings known as Ukrainian varenyky. The dumplings are then twice boiled, coated in a buttered onion sauce, and sold throughout the weekend. The annual proceeds of up to $80,000 go to the church, whose parish is more than a century old.

Varenyky have long been a traditional part of the diet for many of the 70,000 natives of Ukraine who live in the city, and who flock to the luncheonette on weekends from neighborhoods like Brighton Beach, Brooklyn, and Ozone Park, Queens.

Last spring, when four of the elderly women died, the luncheonette closed for several weeks and, like most of the institutions in a once-vibrant Slavic enclave that has since yielded to hipsters, seemed destined to vanish entirely. But on Sept. 9, after a summer of rest and contemplation, the remaining women returned and resumed their labors.

“They will say they won’t do it: ‘I’m not coming back, I’ve had enough of this, I’m tired, I’m worn out, I need to rest,’” said the Very Rev. Bernard Panczuk, the church’s pastor. “And the next week, you look, and they are back.”

Daria Kira, a freckled 85-year-old, embodies the resiliency of this group. She spent 20 days in the hospital last spring after leg surgery to treat cancer. But on the morning of Sept. 9, she woke up at 4 to ensure a timely arrival at the luncheonette’s reopening. The trip took 30 minutes.

Perhaps she came from Brooklyn? “No,” Ms. Kira replied with a sheepish laugh. “From Second and Houston.”

By 10 a.m., she was churning out tissue-thin slices of dough from an archaic wooden rolling machine that may predate its users, who range in age from 64 to “near 100.”

“My leg still hurts me,” said Ms. Kira, who had been on her feet for four hours. “But I work because it’s the church.”

Ms. Kira is chatty; some of her co-workers, among them Julia Warchola, a stern-faced 73-year-old, are less so. “No questions!” she barked at a visitor as she lifted a huge pot of boiling water. “Too much work to do.”

All but two of the women are widowed, and many of them tell harrowing tales about their early life in war-torn Eastern Europe.

Friday, October 30, 2009

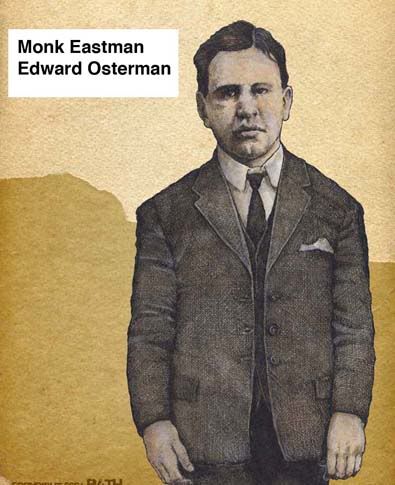

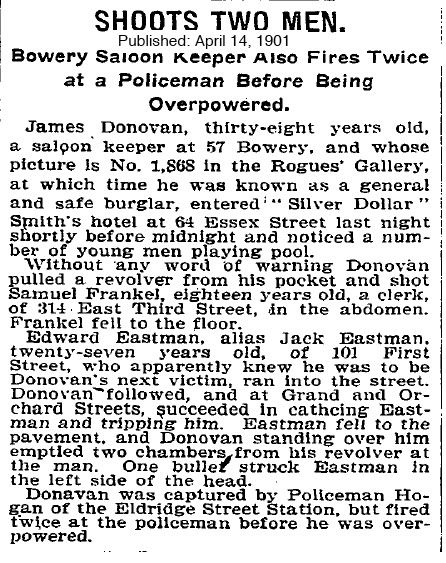

"Halloween" 1901: A Scary LES Dude Of The Past: Monk Eastman

You wouldn't want to mess with Monk. Image by Pat Hamou. Pat has a great mobster site six for five and he sells his art work, very reasonably, on etsy

There's another story about Monk and the Silver Dollar Hotel/Saloon over at the Lower East Side History Project

Monk Eastman, aka: Joseph Morris, William Delaney, Edward Delaney, etc., was born around 1873 in Brooklyn under the name of Edward Osterman. His parents were respectable Jewish restaurateurs and set Edward up with a pet store on Penn street, near their restaurant. Edward grew bored and soon abandoned his store for the excitement of street life, gangsters, prostitutes, stuss games and all of the ilk associated with it. However, Monk (Edward) always held an extreme fondness for cats and birds and he later opened up a pet store on Broome street. Monk trained a pigeon to sit on his shoulder while he went about his street travels and sometimes carried a cat with him. This "sensitive" trait contrasted sharply with his fondness for backjacking assignments and other violent deeds. Monk boasted that he had never struck a women with his club or killed one. When a lady suffered a severe lapse in manners, he blackened her eyes.

"I only give her a little poke, just enough to put a shanty on her glimmer. But I always takes off me knucks first."

Around 1895, Monk moved to lower Manhattan and established himself as Sheriff of New Irving Hall. The "Sheriffs" acted as armed bouncers and were responsible for keeping order (of sorts) in the social clubs or resorts that were frequented and owned by gangsters/politicians. Monk developed a patois of clipped, slangy speech and an indifferent dress style. The artist's rendition of Monk shows him at his best, usually only when he was before a magistrate. Monk became very popular with the hoodlums of the East Side and they began to imitate his slang and sloppy clothes. Monk's outfit usually consisted of a derby hat several sizes too small, a blackjack tucked into his pants, open shirt, and brass knuckles adorning each hand. He carried a large club and enjoyed using it, "sending so many men to Bellevue Hospital's accident ward that ambulance drivers referred to it as the Eastman Pavilion."

After a few years, Monk quit his position as Sheriff of New Irving and moved up the crime ladder towards gang leader. Monk had established his kingdom by 1900 with more than twelve hundred warriors under the Eastman banner. The Eastman headquarters was a dive on Chrystie street, near the bowery, where they stockpiled slung-shots, revolvers, blackjacks, brass knuckles, and other tools of gang warfare. Their main sources of income were derived from houses of prostitution, stuss games (a form of faro), political engagements, blackjacking services, and the operations of pickpockets, footpads, and loft burglars. Tammany Hall, the political power in New York City, frequently engaged the services of Eastman to bring in the votes at election time. In return, Tammany Hall lawyers bailed Eastman out whenever he got arrested.

Monk Eastman's feud with Paul Kelly began over a strip of territory between Mike Salter's dive on Pell street and the Bowery. Eastman claimed domain over the territory from Monroe to Fourteenth streets and from the Bowery to the East River. Paul Kelly and his Five Pointers believed that their kingdom included the Bowery and any spoils found in this area. Eventually, the constant feuding would cause the downfall of both Monk Eastman and Paul Kelly.

Sunday, October 25, 2009

A New Look At The Other Half

Riis New Book

Daniel Czitrom co-authored a recent book which re-examines the work of Jacob Riis.

An excerpt from the nytimes review

Daniel Czitrom co-authored a recent book which re-examines the work of Jacob Riis.

An excerpt from the nytimes review

Today one of the last Bowery flophouses leans up against the futuristic steel facade of the New Museum, and a bed at the Bowery Hotel can run $750 a night. After such gentrification, it can be difficult to conjure up the squalid New York that Jacob Riis documented in his groundbreaking 1889 work of photojournalism, “How the Other Half Lives.” Riis was well aware that the “other half” in New York City had become the other three-quarters, with 1.2 million impoverished New Yorkers living in slums, 19th-century tenements that were a public health catastrophe, rife with typhus, diarrhea, cholera and tuberculosis. Employing unsentimental storytelling, reportage, social statistics and the latest advances in flash photography, Riis shed a stark light on the horrific living conditions of New York’s vast population of poor immigrants.

In “Rediscovering Jacob Riis,” Bonnie Yochelson and Daniel Czitrom have undertaken a rigorous, scholarly re-examination of Riis’s life and work. While Czitrom, a historian at Mount Holyoke College, places Riis in the context of other 19th-century social crusaders, Yochelson, a former photo curator at the Museum of the City of New York, offers a more critical assessment; she re-evaluates Riis’s photography and questions the mythos that surrounds him.

Riis was beloved in his time. Teddy Roosevelt called him “the best American I ever knew,” and even coined the term “muckraking” to describe the fierce advocacy journalism practiced by Riis and others. But Riis was far from an infallible social reformer. In Czitrom’s estimation, he refused to acknowledge his debt to predecessors like the activist-journalist Charles Wingate and too often indulged in ethnic stereotyping. An industrious Danish immigrant, he seemed to find moral failings in nearly every other group: Polish Jews, Italians, Chinese, the Irish. Riis was also critical of interracial socializing; he said of so-called black-and-tan saloons that “there can be no greater abomination.” But Riis’s real anger was saved for the tenements themselves, whose dire conditions he called the “murder of the home.” He pursued his campaign with evangelical zeal. Riis believed that defective character led to poverty and that conscience-driven capitalism was the best solution. Although he pitied them, his reform crusade “ascribed little or no role at all to tenement dwellers themselves,” Czitrom writes. This brand of noblesse oblige perhaps anticipated the public housing failures of Riis’s 20th-century admirer Robert Moses.

But regardless of his philosophy, Riis’s photographs remain indelible. Making use of newly invented magnesium flash powder, he brought the brilliant light of a new medium to bear on a netherworld that had never been photographically recorded. He shot the down-and-out occupants of darkened Bowery basements and Chinatown opium dens, his subjects caught unawares. The dingy and cluttered rooms, lighted bright as day for a split-second exposure, are immediate and revelatory, and remain extraordinarily persuasive as evidence of the squalor Riis sought to combat.

Friday, October 16, 2009

Chuck Connors, A Mayor Of Chinatown

from the Bowery Hall Of Fame

Chuck Connors, born George Washington Connors, had a trait that made him very popular in the press: a willingness to be quoted saying anything. As a result, Connors is credited with inventing the phrases, “the real thing,” “oh, good night,” “oh, forget it,” and “under the table.” Connors’ primary claim to fame is his autobiography Bowery Life, ghostwritten by reporter and editor Richard K. Fox of The Police Gazette.Connors was most likely born in Providence, RI, although he claimed to be born on Mott Street. As a child in New York City he worked odd jobs, including a gig as a clog dancer in the Gaiety Museum. He grew up tormenting the Chinese by pulling their pigtails, but eventually learned some Mandarin--earning him his nickname, the Mayor of Chinatown. As an adult Connors worked as a bouncer in a variety of dive bars. He married, in a brief stint at an “upstanding life,” but it ended when his wife passed away. Connors traveled to London to recover, and returned with a new outfit: bell bottomed trousers, a blue-striped shirt, a bright silk scarf, a pea coat, and big pearl buttons. This was known as the Connors look. He even had a song to describe his outfit:

Pearlies on my shirt front

Pearlies on my coat

Little bitta dicer,

stuck up on my nut

If you don’t think I’m de real t’ing

Why, tut, tut

Connors also became well known as a tour guide for celebrities, prominent authors and royalty. Connors’ reputation as a friend of the Chinese made him a convincing guide to his danger-seeking clientele, who believed him when he identified innocent passers-by as hatchet men. Connors also created bogus opium dens, where the “fiends” paid no attention to the tour groups passing through. He also capitalized on his fame by throwing galas for the Chuck Connors Association, a charity benefiting Connors himself.

The character of Chuck Connors was played by Wallace Beery in the 1933 film the Bowery

Labels:

bowery,

chinatown,

chuck connors,

Ward 4,

ward 6

Friday, June 26, 2009

New York's Bunker Hill

from pseudo-intellectualism in August of 2005

from pseudo-intellectualism in August of 2005 Follow the path: The 1894 map led to a search for more info on the People's Theater on the Bowery. Unearthed was information on forgotten-ny's site about Bunker Hill. This provides a more complete solution to the Paradise Alley question of where was the exact site of the Bunker Hill that Tom went to view a bull being tortured by wild dogs.

Monday, June 22, 2009

Friday, June 19, 2009

Steve Brodie's Bar, 114 Bowery: Then And Now

from the Bowery Boys

The nightlife of the old Bowery could be an entire blog in itself. It has been witness to some of the most rowdy, shameless and debauched New Yorkers who have ever lived. They filled up dives and flophouses, brothels and saloons, catered to the poorest of immigrants and the richest of the upper class 'slumming it' for a real idea of fun unimagined in the drawing rooms of the elite.

The two saloons from the late 19th century featured here weren't extraordinary places as we would consider today -- they would both fit comfortably in the 20th century sin-den the Limelight -- but they were run by extraordinary people, 'heroes' of the Bowery brawler set.

Geoghegan's at 105 Bowery has been described as "a rendezvous for professional mendicants." Often called the Bastille of the Bowery, it didn't just spawn a few fisticuffs; it catered to them. Because this two floor booserie featured two boxing rings, and one of the men in the ring was often the bar's owner.

Owney Geoghegan held the boxing distinction of Lightweight Champion of America from 1861 to 1964, when he retired to open his tavern/fight palace in the Bowery. His reputation naturally drew the crowds, and Geoghegan encouraged his patrons on to a little pugilism with the help of ample ales and whiskey. In 1891 the 'Bastille' even hosted a few rather fierce bouts of women's wrestling, with the competitors required to cut their hair (to prevent pulling) and costume themselves wearing only tights.

Such a swarthy establishment was bound to attract the lowest elements and the most sinful gangs of New York. One journalist at the time describes it: "The faces around us are worse than those seen in a bench show of pugnacious dogs, and instinct teaches us to have a care for our nickels, for our pockets are in imminent danger."

But perhaps the person the clientele should have feared the most was Geoghegan himself. A short but powerful Irish man, Geoghegan was known for his impressive, compact strength. And his penchant to cheat when needed.

Geoghegan was in the ring one night against Viro Small, a very popular black wrestler. Geoghegan was still in his prime but it was clear he was being bested in the ring by Small. The drunken crowd catcalling him, and he knew he couldn't lose in his own establishment. So he had one of his henchman hold a gun to the referee's head and call the match for Geoghegan!

(Small didn't hold a grudge. He later wrestled there again, with a man named Billy McCallum who afterwards tried to murder him.)

As Geoghegan flexed his strength to his barflys, another Bowery saloon owner was busy displaying his gifts of agility. In 1886 Steve Brodie, on a bet, jumped off the Brooklyn Bridge, the bridge being only about three years old at the time. What was amazing was not the amount of stupidity that took, but the fact that he survived and claimed his $100 bet money.

His feat was celebrated at the time and from the fame of this simple act, he was able to open Steve Brodie's Saloon, 114 Bowery, at Bowery and Grand Street (a couple doors down from Geoghegan's place).

If Geoghegan's dive was a celebration of his profession, Brodie's was a celebration of his own personality. Behind the bar was an elaborate oil painting depicting Brodie bravely hurling off the bridge, along with a signed affidavit from the boat captain who fished him out of the water. The floor of the bar was inlaid with silver dollars to give it that wealthy feeling that money had been hurled to the floor.

For the cost of a drink, Brodie would gladly recount his tale. As silly as it seems today, he was able to pack in patrons, perhaps many from Geoghegan's place, still drunk on booze and bloodletting.

Somehow he managed to turn his feat into a touring autobiographical performance entitled 'On The Bowery'. Eventually he tried to top his feat with a plunge down Niagara Falls in 1889. (It could never be proven that he actually went ahead with it!) He settled in Buffalo and opened another saloon there, but the enigma of his fame apparently didn't carry that far. He moved to San Antonio and died at age 38.

Owney Geoghegan had a similar short-lived fate. He lapsed into a severe depression at the death of his father and, traveling to Hot Springs, Ark., to try cure himself of his pain, actually died there, age 45.

Owney Geoghegan Of The Bowery

geoghegan

Owney Geoghegan (1840 – January 19, 1885) was a lightweight bare-knuckle boxer. Geoghegan claimed the Lightweight Championship of America in 1861, and held it until his retirement in 1863. He stood 5’ 6”, and weighed between 130 and 140 pounds.

Geoghegan was born in 1840 in Ireland. He traveled to the United States in 1849 and settled in New York[1] His first recorded prize-fight took place in 1860 against Jim McGann in New York. Geoghegan won the bout in five rounds and 15 minutes. That same year, he defeated Deaf Moran, Bill Dukes, Arthur Gowan, and held a draw with Mike Donohue.

Patrick “Scotty” Brannagan retired as Lightweight Champion of America in 1861, and a contest was held between Geoghegan and Eddie Touhey to fill the vacant title. The two men met on April 18, 1861 in New York. Although Toughey was a better boxer, Geoghegan wore his opponent down with his incredible strength. After 45 rounds, and 61 minutes, Geoghegan was declared the new champion.

Between 1861 and 1863 he defended his title against Bob Slaon, Chick Sullivan, Banty Edwards, and Pat Devlin before being challenged by the 144-pound Con Orem.

The bout between Geoghegan and Orem took place near South Amboy, New Jersey on May 15, 1863. After 19 rounds and 23 minutes, Geoghegan was declared the winner, when his opponent committed an illegal foul. After this contest, Geoghegan relinquished his title and retired from the ring.

Shortly after retirement, he opened a sporting house known as “The Bastille of the Bowery”. By 1885, he had opened several gambling houses and was known to give sparring exhibitions.Following the death of his father, Geoghegan slipped into a severe depression. He died soon after, in Hot Springs, Arkansas. Geoghegan was said to have left behind upwards of $100,000.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)