Bert Lahr (August 13, 1895 – December 4, 1967) was an American Tony Award-winning comic actor.

Born Irving Lahrheim in New York City, Lahr is best remembered today for his role as the Cowardly Lion and the Kansas farm worker Zeke in the classic 1939 movie The Wizard of Oz, but known during his life for a career in burlesque, vaudeville and Broadway.

Dropping out of school at the age of fifteen to join a juvenile vaudeville act, Lahr worked his way up to top billing on the Columbia Burlesque Circuit. In 1927 he debuted in on Broadway in Harry Delmar's Revels. Lahr played to packed houses, performing classic routines such as "The Song of the Woodman" (which he later reprised in the film Merry-Go-Round of 1938). Lahr had his first major success in a stage musical playing the prize fighter hero of Hold Everything (1928-29). Several other musicals followed, notably Flying High (1930), Florenz Ziegfeld's Hot-Cha! (1932) and The Show Is On (1936) in which he co-starred with Beatrice Lillie. In 1939, he co-starred with Ethel Merman in DuBarry Was a Lady.

Lahr made his feature film debut in 1931's Flying High, playing the part of the oddball aviator he had previously played on stage. He signed with New York-based Educational Pictures for a series of two-reel comedies. When that series ended, he came back to Hollywood to work in feature films. Aside from The Wizard of Oz (1939), his movie career was limited.

Showing posts with label minskys. Show all posts

Showing posts with label minskys. Show all posts

Sunday, January 9, 2011

Bert Lahr: The Night They Raided Minskys

Saturday, January 8, 2011

National Winter Garden

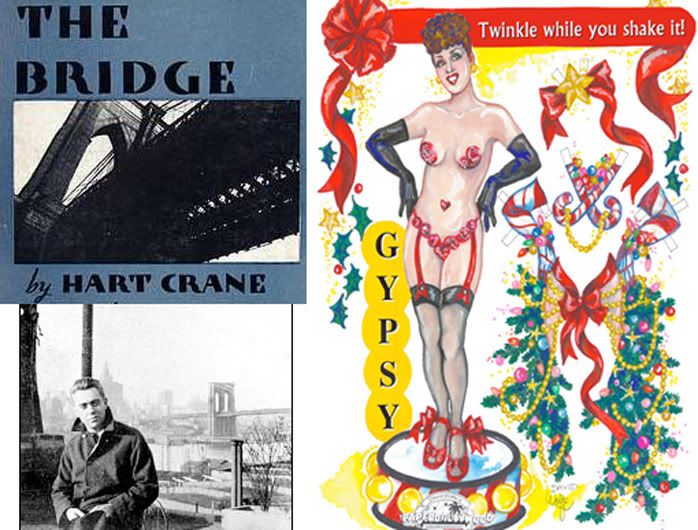

The Bridge, first published in 1930 by the Black Sun Press, is Hart Crane's first, and only, attempt at an American long poem. (Its primary status as either an epic or a series of lyrical poems remains contested; recent criticism tends to read it as a hybrid, perhaps indicative of a new genre, the 'modernist epic.'

The Bridge was inspired by New York City's "poetry landmark", the Brooklyn Bridge. Crane lived for some time at 110 Columbia Heights in Brooklyn, where he had an excellent view of the bridge; only after The Bridge was finished did Crane learn that one of its key builders, Washington Roebling, had once lived at the same address.

The Bridge comprises 15 short poems, here's one of them. It's inspiration was mentioned previously:

About Hart Crane

The Bridge was inspired by New York City's "poetry landmark", the Brooklyn Bridge. Crane lived for some time at 110 Columbia Heights in Brooklyn, where he had an excellent view of the bridge; only after The Bridge was finished did Crane learn that one of its key builders, Washington Roebling, had once lived at the same address.

The Bridge comprises 15 short poems, here's one of them. It's inspiration was mentioned previously:

NATIONAL WINTER GARDEN.

by Hart Crane

Outspoken buttocks in pink beads

Invite the necessary cloudy clinch

Of bandy eyes. . . . No extra muffling here:

The world’s one flagrant, sweating cinch.

And while legs waken salads in the brain

You pick your blonde out neatly through the smoke.

Always you wait for someone else though, always–

(Then rush the nearest exit through the smoke).

Always and last, before the final ring

When all the fireworks blare, begins

A tom-tom scrimmage with a somewhere violin,

Some cheapest echo of them all–begins.

And shall we call her whiter than the snow?

Sprayed first with ruby, then with emerald sheen–

Least tearful and least glad (who knew her smile?)

A caught slide shows her sandstone grey between.

Her eyes exist in swivellings of her teats,

Pearls whip her hips, a drench of whirling strands.

Her silly snake rings begin to mount, surmount

Each other–turquoise fakes on tinselled hands.

We wait that writhing pool, her pearls collapsed,

–All but her belly buried in the floor;

And the lewd trounce of a final muted beat!

We flee her spasm through a fleshless door. . . .

Yet, to the empty trapeze of your flesh,

O Magdalene, each comes back to die alone.

Then you, the burlesque of our lust–and faith,

Lug us back lifeward–bone by infant bone

About Hart Crane

Hart Crane (1899-1932) was an American poet. Finding both inspiration and provocation in the poetry of T. S. Eliot (Crane’s The Bridge was allegedly written directly in response to Eliot’s The Wasteland), Crane wrote poetry that was traditional in form, difficult and often archaic in language, and which sought to express something more than the ironic despair that Crane found in Eliot’s poetry. Though frequently condemned as being difficult beyond comprehension, Crane has proved in the long run to be one of the most influential poets of his generation.

Crane was gay, and, much like his contemporaries (and a significant number of poets and artists throughout the ages), suffered from depression and a drinking problem. Although he experienced some success as a writer in the early and mid 1920′s, his depression and drinking won out, as did his belief that one could not be happy as a homosexual, and in 1932 he committed suicide by jumping off a steamship into the Gulf of Mexico.

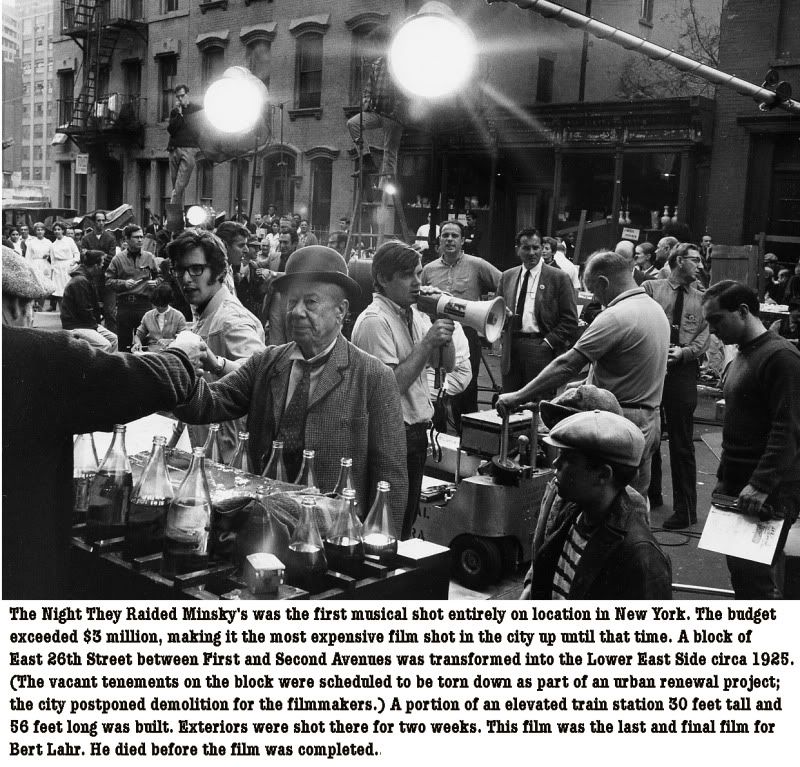

The Night They Raided Minskys

cont'd from previous post

Billy realized that while burlesque could not be classy, it could be presented in classy surroundings. In 1931 he proposed bringing the Minsky brand to Broadway, amid the respectable shows. The brothers leased the Republic Theater on 42nd Street and staged their first show on February 12. The Republic became Minsky's flagship theater and the capital of burlesque in the United States. (The theater is now called the New Victory and, ironically, specializes in children's entertainment.) Other burlesque shows were inspired to open on 42nd Street at the nearby Eltinge and Apollo Theaters.

The Great Depression ushered in the greatest era for burlesque, and Minsky burlesque in particular. Few could afford to attend expensive Broadway shows, yet people craved entertainment. Furthermore, there now seemed to be an unlimited supply of unemployed pretty girls who considered the steady work offered by burlesque. By the time they finished expanding, the various Minskys controlled over a dozen theaters – six in New York and others in Baltimore, Philadelphia, Albany, and Pittsburgh. They even formed their own "wheel."

Minsky's featured comics Phil Silvers, Joey Faye, Rags Ragland and Abbott and Costello, as well as stripper Gypsy Rose Lee. Others included, Red Buttons and Robert Alda, as well as strippers, Georgia Sothern, Ann Corio, Margie Hart, and Sherry Britton. These women, who began stripping in their teens, made between $700 and $2,000 a week.

With burlesque thriving in New York (there were now 14 burlesque theaters, including Minsky's rivals), competition was fierce. Each year, various license commissioners issued restrictions to keep burlesque from pushing the limits. But convictions were rare, so theater managers saw no need to tone down their shows.

In 1935, irate citizens' groups began calling for action against burlesque. Fiorello H. LaGuardia, had deemed them a "corrupting moral influence". The city's license commissioner, Paul Moss, tried to revoke Minsky's license but the State Court of Appeals ruled that he did not have grounds without a criminal conviction. Finally, in April, 1937, a stripper at Abe Minsky's New Gotham Theater in Harlem was spotted working without a G-string. The ensuing raid led to the demise not only of Minsky burlesque, but of all burlesque in New York. The conviction allowed Moss to revoke Abe's license and refuse to renew all of the other burlesque licenses in New York.

After several appeals, the Minskys and their rivals were allowed to reopen only if they adhered to new rules that forbade strippers. The owners went along, hoping to stay in business until the November election when reformist mayor Fiorello La Guardia might be voted out. But business under the new code was so bad that many New York burlesque theaters closed their doors for good. By the time La Guardia was re-elected, the word "burlesque" had been banned and, soon after, the Minsky name itself, since the two were synonymous. With that final blow, burlesque and the Minskys were finished in New York.

Of all the Minskys, only Harold, Abe's adopted son, remained active in burlesque. Harold started in the business at age nineteen at the height of the Great Depression, learning the business by working in all facets from the box office to theater management. By his early twenties Harold had already produced shows.

In 1956 Harold brought the Minsky name to a Las Vegas revue at the Dunes, where it could exist without apology. That revue ran for six years; subsequently, he moved Minsky productions into other landmark casinos such as the Silver Slipper, the Thunderbird, and The Aladdin.

Harold resided in Las Vegas until his death in 1977.

The Minsky Family

When they got rich the Minsky family moved uptown to 97th Street, near 5th Avenue.

Minsky's Burlesque refers to the brand of burlesque presented by the four Minsky brothers: Abe Minsky (1878–1960); Billy Minsky (1887–1932); Herbert Minsky (1892-?); and Morton Minsky (1902–1987).They started in 1912 and ended in 1937 in New York City. Although the shows were declared obscene and outlawed, they were rather tame by modern standards.

The eldest brother, Abe, launched the business in 1908 with a Lower East Side nickelodeon showing racy films. His own father shut him down and bought the National Winter Garden on Houston Street, which had a theater inconveniently located on the sixth floor. He gave the theater to Abe and his brothers Billy and Herbert. At first they tried showing respectable films but could not compete with the large theater chains. The Minskys tried to bolster their shows by bringing in vaudeville performers, but could not afford good acts.

Then they considered burlesque. Burlesque acts were cheaper, and circuits (called "wheels") supplied a new show every week, complete with cast, costumes and scenery. There was the Columbia Wheel, the American Wheel, and the Mutual Wheel. Burlesque during this period was "clean"; a fourth wheel, the Independent, actually went bankrupt in 1916 after refusing to clean up its act. The Minskys briefly considered signing with a wheel but decided to stage their own shows because it was cheaper and Billy longed to be the next Florenz Ziegfeld.

But Minsky's clientèle of poor immigrants had not been taught to appreciate clean burlesque, and the Minskys were not about to teach them. Plus, their audience needed a compelling reason to trek up to a sixth-floor theater. Billy realized that success in burlesque depended on how the girls were featured. Abe, who had been to Paris and the Folies Bergère and Moulin Rouge, suggested importing one of their trademarks: a runway to bring the girls out into the audience. The theater was reconfigured, and the Minskys were the first to feature a runway in the United States. Billy had the sign out front changed to "Burlesque As You Like It – Not a Family Show," and the Minskys were on their way.

The Minskys were raided for the first time in 1917 when Mae Dix absent-mindedly began removing her costume before she reached the wings. When the crowd cheered, Dix returned to the stage to continue removing her clothing to wild applause. Billy ordered the "accident" repeated every night. This began an endless cycle: to keep their license, the Minskys had to keep their shows clean, but to keep drawing customers they had to be risqué. Whenever they went too far, they were raided.

Morton joined the company in 1924, after graduating from New York University, and worked at the Little Apollo Theater on 125th Street. There was a raid during the very first show. For the next four years, the theater showed a weekly profit of $20,000 after payola.

Billy's attempt, however, to present classy burlesque at the Park Theater on Columbus Circle failed miserably.

Another famous raid occurred in April, 1925, and inspired the book and film The Night They Raided Minsky's. By this time it was permissible for girls in shows staged by Ziegfeld, George White and Earl Carroll – as well as burlesque – to appear topless as long as they did not move (a similar rule in London burlesque was famously demonstrated in the film Mrs. Henderson Presents). In a show at the National Winter Garden, Madamoiselle Fifi (née Mary Dawson from Pennsylvania) stripped to the waist and then moved.

Occasionally a raid was triggered by the comedy material, but filthy comics did not last long because they were a liability to the management.

Business boomed during Prohibition and the National Winter Garden's notoriety grew. Regular patrons included John Dos Passos, Robert Benchley, George Jean Nathan, Condé Nast, and Hart Crane (see Crane's poem "National Winter Garden" in The Bridge).

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)