Another local gang of the Lower East Side, the Shirt Tails of Corlear's Hook, most likely fought with the Cherry Hill gang, the Batavia Street gang, or maybe even bothYou can read more about the Batavia's foiled robbery in the The American Metropolis. The Tweed bio referenced above is called "Boss Tweed: The Story of a Grim Generation."

We're finally stepping away from the grime of the late 19th century, but not before giving a little shout-out to possibly one of my favorite gangs of the era, the Cherry Hill Gang.

Not much is known about them -- street gangs don't traditionally leave exhaustive archives about themselves -- but current descriptions usually use one word to describe them : dandies.

Cherry Hill was the decrepit neighborhood near the waterfront in the Fourth Ward, lined with tenements as awful (and sometimes worse) as the ones in Five Points. Its resident mix of Jewish and Italian suffered the same conditions as those in other poor neighborhoods, and hard times dealt its share of saloons, prostitution, crime and ruffians.

An early variation of the gangs of Cherry Hill included young William 'Boss' Tweed as their leader. According to an early bio on Tweed, the Cherry Hills rivals were the boys on Henry Street, just three blocks away. According to author Denis Tilden Lynch, it was important to stay clean on your turf and spar on somebody elses:

"A gang, to survive, must be peaceful in its own neighborhood. Its petty offenses are invariably directed against peaceful citizens of distant streets. Piracy would never have been an honored profession if the black flag flew only in home waters."

By the 1890s, the "roughs" of Cherry Hill had literally re-tailored themselves. To rob the rich, one must be able to mingle with them convincingly. So the Cherry Hill gang was known for their impeccable dress sense, their stolen funds apparently used to acquire elegant, dressy outfits of the day. Topping these foppish costumes were walking sticks tipped in metal to better thwack an unsuspecting victim.

The Bowery Boys of the 1850s and 1860s were also known as sharp dressers; however their dress sense reflected their well established reputation and political power. The Cherry Hills meanwhile dressed for success merely to infiltrate rich neighborhoods and rob unsuspecting gentlemen. And apparently to intimidate local rivals.

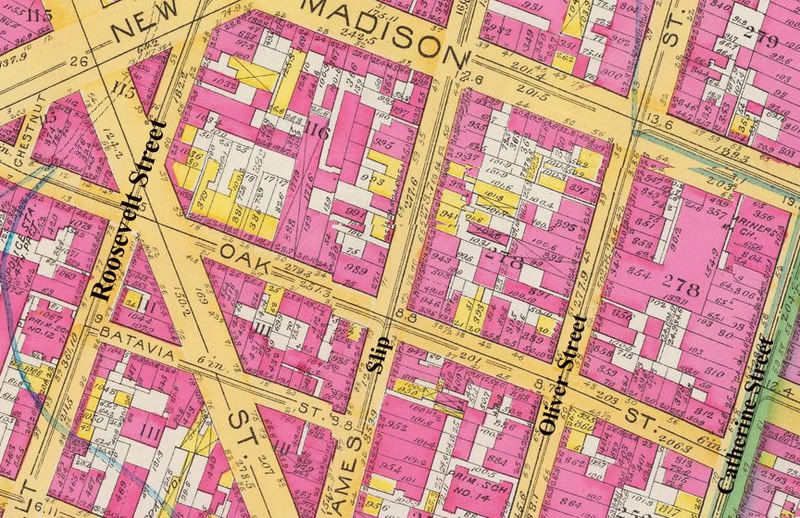

The primary rival of the Cherry Hill gang was the local Batavia Street gang. Batavia Street was a former street in the same area, "in the shadow of the Brooklyn Bridge" and apparently in one account was "the most [Charles] Dickensy street in New York." (It's also referred to in some accounts as Batavia Lane, but the Batavia Lane Gang doesn't sound very menacing, does it?)

Like some Gilded Age variation of West Side Story, the Cherry Hill gang and the Batavia Street gang were set to meet on the dance floor of New Irving Hall (once located on 214 Broome Street). Lower East Side balls in the late 19th century were modeled after their upper class variations, but were far rowdier and certainly more fun.

The Cherry Hill gang were set to dazzle in their finest ensembles, certainly intending to steal the show (if not steal more material things in the process). The Batavias would not be outdone but were desperately broke. After the pawning of a stolen gold watch from Herman Segal's jewelry shop failed to produce enough cash for fancy new threads, the jealous gang returned to the jewelry store and simply smashed the window in, running off with 44 gold rings "worth from $3 to $45 dollars apiece.

The Batavias were eventually captured -- while trying on their newly bought suits, no less, on Division Street -- and thrown in the Tombs. Apparently the Cherry Hill gang attended the ball as planned. They would eventually go on to influence the dress sense of other street gangs. New York has changed so drastically in the 110 years since the New Batavia ball, but it's nice to see that the superficial love of fashion has never been altered.

Showing posts with label gangs of new york. Show all posts

Showing posts with label gangs of new york. Show all posts

Monday, July 25, 2011

More On Batavia Street And The Batavia Street Gang

From the bowery boys

Labels:

batavia street,

bowery boys,

gangs of new york

Batavia Street And The Batavia Street Gang

Joseph Giuga, perhaps an ancestor of Linda, living at 19 Batavia in 1910 probably had to watch out for these guys

Batavia Street Gang was a New York independent street gang based in the Fourth Ward during the 1890s. Affiliated with the Eastman Gang during the turn of the century, they were rivals of the Cherry Hill Gang throughout the previous decade. During one incident, five members of the gang were arrested for breaking into Seigel's jewelry store in order to purchase costumes for the Sullivan ball at New Irving Hall in an attempt to out do their rivals, who were known to be "dandies", had announced they would be attending in extravagant evening clothes.

Stealing a gold watch from Seigel's jewelry store, Duck Reardon and Mike Walsh organized a raffle with the Sullivan Association at Coyne's saloon and, arranging it so that fellow gang member James Leary would win the watch. However, as neither the income from the raffle, nor the watch failed to raise enough money to purchase suits for the other gang members, their leader Duck Reardon, and several others, smashed in the front window of a local jewelry store and stole 44 gold rings ranging from $3-$45 in value.

After reporting the robbery to police, detectives from the Oak Street Police Station arrested several members of the Sullivan Association including Reardon, Arthur Hassett, George and Jerry Leary and Chuck Conners (not related to the ward boss of the Bowery and Chinatown), as well as tug boat hand Mike Walsh, who had purchased one of the stolen rings from Reardon (reportedly while they were trying on suits at a local Division Street tailor shop).

Held at the Center Street Police Court, the five were tried before a Magistrate Cornell who ordered Reardon, Hassett, Connors and Walsh to pay $1,000 while George Leary was charged $300 for stealing the gold watch. However, no charges were brought against Jerry Leary and he was later released.

Saturday, January 8, 2011

Gypsy Rose Lee's Lower East Side Gangster Boy Friend

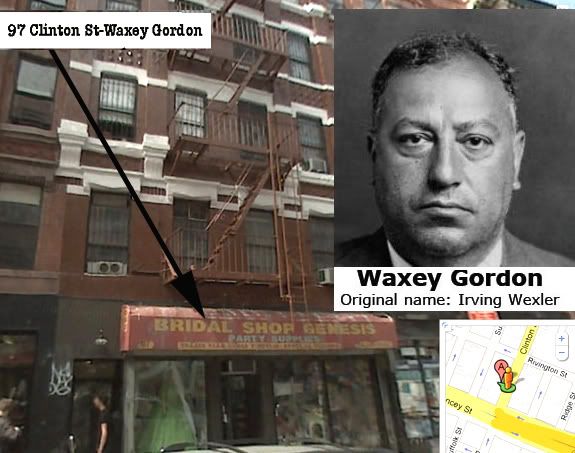

Waxey lived on Clinton Street several years before this occured. Prohibition changed things considerably. About Gypsy and Waxey from Karen Abbott's new biography

In 1931, when Waxey met Gypsy Rose Lee in a Manhattan speakeasy, he was 43 years old and married, with three children. He kept his family in a ten-room, four-bath apartment at 590 West End Avenue (paying $6,000 per year in rent at a time the average annual salary was $1,850) and decorated with the help of professionals, including a woodsmith who custom-built a $2,200 bookcase. Five servants catered to their every whim. His children attended private schools, took daily horseback riding lessons in Central Park, and spent summers at their house in Bradley Beach, NJ. He owned three cars, bought $10 pairs of underwear by the dozen, and stocked his closets with $225 suits tailor-made for him by the same haberdasher who outfitted Al Capone. In 1930, Waxey made nearly $1.5 million and paid the United States government just $10.76 in taxes.

Gypsy was just 20 years old at the time and worried obsessively about money—“Everything’s going out,” her mother, Rose, warned her daily, “and nothing’s coming in.” She had just scored her first big break in burlesque, working as a headliner for Minsky’s Republic on Broadway, but the days of starving on the old vaudeville circuit, eating dog food just to stay alive, were still fresh in her mind

Saturday, December 25, 2010

The Untouchables And Almost KV

Plot Summary for "The Untouchables" Stranglehold (1961)from the internet movie database

Frank Makouris, associated with the New York mob and Dutch Schultz, controls the city's Fulton Fish Market which provides much of the fish in the Eastern United States. Anything the fisherman might need - docking rights, ice, wholesalers - can only be had with a payment to Makouris. Eliot Ness is invited by the US Attorney in New York to help bring Makouris down. They find that one fisherman in particular, Capt. Joe McGonigle, is prepared to help them out but even then, Makouris manages to have Ness' phone tapped and they get to McGonigle before he can testify. Ordered by the mob bosses to knock off the violence, Makouris oversteps the mark and the Syndicate orders him to get rid of his enforcer, Lennie Shore.Ricardo Montalban as a Greek!

Tuesday, April 6, 2010

Filming Boardwalk Empire

I just happened to stumble upon this set coming back late one night to Brooklyn from Worcester

the hbo series site

Not really Gangs of New York, but Gangs of New Jersey. I'm sure there will be an overlap

Monday, March 22, 2010

Thursday, March 4, 2010

1871 Faro Game Raid Nets A 63 Madison Street Tenant

Faro 63 Madison

Joseph Young was the unlucky guy to get arrested. We don't know of his luck with faro.

faro explained

Joseph Young was the unlucky guy to get arrested. We don't know of his luck with faro.

faro explained

Labels:

gangs of new york,

madison street,

nytimes,

Ward 4

Thursday, January 14, 2010

The French Connection Updated

I thought I'd used this clip to "place hold" for some stories of how, despite the cooked statistics, the city and the LES can still be a gritty place

an excerpt from the lowdown

The police may very well "know about it," but they clearly have no interest in discussing what's happening on the streets. This past month, during an interview with The Lo-Down, a precinct captain abruptly ended an interview when the subject of gang violence came up. The Village Voice, apparently, got a similar response:

We asked Paul Browne, the NYPD's spokesman, about these perceptions, and also requested crime stats that might show whether youth crime was indeed surging, but he didn't respond to our e-mail.

an excerpt from the villagevoice

In a Crime-Free City, How Does a Young Gangbanger Represent?, By Graham Rayman

You now live in the safest New York City that has existed since the Beatles came to America. Murders are now so rare—at least for a city this size—that you have to go back to the Kennedy administration to find similar numbers. Just ask Mayor Bloomberg. Like a kind of political Tourette's syndrome, he tells you that's the case every chance he gets. New York is now so tame that old-timers grumble that it's become a boring town and wish openly for at least a little of 1977's grit and grime.

So considering what a patsy your metropolis is now, it's hard to believe any of you are going to be alarmed at what some young people in the Lower East Side are telling us—that actually, for them, this town is still a jungle.

Yeah, we had the same reaction.

Prove it, kid.

There's this one street kid—we'll call him Johnny—who's 18 and lives with his asthmatic grandmother and cousins in a cramped East 12th Street apartment because his father kicked him out of their apartment and his mom left the city. He says he's on probation for five years, which stemmed from a robbery arrest. He says he knocked someone over and took their cash so he could buy lunch. He says he's been jumped and beaten with metal bats. He says he's afraid to walk past certain public housing projects that he considers rival gang territory. He wants to leave the neighborhood, but feels like he has no other option than to stay.

Johnny describes a world of young louts endlessly roaming the streets, of the constant presence of drugs, of brazen instigators who post YouTube videos to make threats and call out other groups and who fill MySpace pages with tough-guy images and over-the-top boasts. These wannabes and badasses associate themselves with the public housing projects they live in, giving themselves colorful names like Money Boyz in the Campos Houses, and No Fair Ones (NFO) in the Smith Houses.

an excerpt from the Villager

Mothers are ganging up to fight youth violence on East Side. A spate of violent incidents in the East Village over the past three months has prompted two women to tackle the problem of gangs and violence the only way they know how — as mothers.

Aida Salgado, 40, and Maizie Torres, 42, are now partners against crime in a new organization they have founded called Mothers in Arms. The initiative aims to get parents more involved in ensuring that their children are safe and are engaged in constructive activity, such as after-school programs and recreational activities, to deter them from joining local gangs.

The Police Department did not make available statistics on gang-related activity. But the fatal stabbing of Glenn Wright, 21, by an alleged gang member at the Baruch Houses on Sept. 12 was one recent incident that served as a harsh reminder that gang violence still exists in the neighborhood.

“We want to get parents more involved and educate them about these matters,” said Salgado, who suspects that many parents are in the dark about their own children’s activities. “They need to know where their children are and who they hang out with.”

Salgado’s and Torres’s own sons grew up in an environment dominated by gangs. The mothers say many of their sons’ friends are gang members. Resisting the peer pressure to join gangs is a major challenge for both of their children. But through Mothers in Arms, the women hope that parents will play a more active role in preventing their children from getting involved in violence.

Friday, October 30, 2009

The Max Hochstim Association, AKA The Essex Market Court Gang

Eastman Smith Engel

much from the pdf above comes from the Rise and Fall of the Jewish Gangster in America by Albert Fried

Hochstin, along with Tammany boss Martin Engel, had saloons/houses of prostitution at 102, 121, and 123 Allen Streets and 33 Madison Street.

much from the pdf above comes from the Rise and Fall of the Jewish Gangster in America by Albert Fried

Hochstin, along with Tammany boss Martin Engel, had saloons/houses of prostitution at 102, 121, and 123 Allen Streets and 33 Madison Street.

Charles "Silver Dollar Smith" Solomon

Silver Dollar Smith

from wikipedia's entry on historical criminals of New York

There's more about Charles "Silver Dollar Smith" Solomon and his association with Monk Eastman over at the Lower East Side History Project

an excerpt

from wikipedia's entry on historical criminals of New York

1843-1899 Tammany Hall political organizer known as "Silver Dollar Smith". Solomon was the political boss of the old Tenth Ward district and owner of the Silver Dollar Saloon in Essex Street across the street from Market Street Court.

There's more about Charles "Silver Dollar Smith" Solomon and his association with Monk Eastman over at the Lower East Side History Project

an excerpt

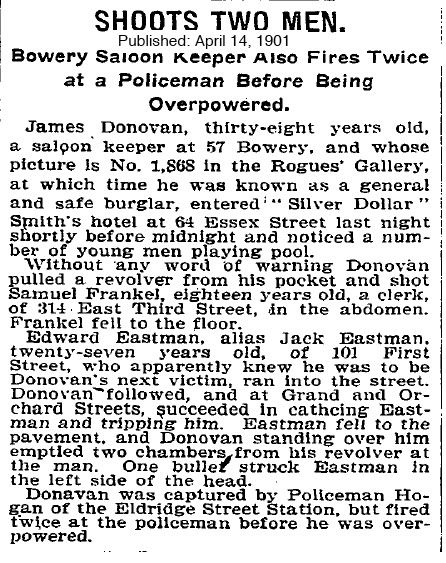

Smith's saloon was one of the sites of operation for the Eastman Gang, run by Jewish gang leader Monk Eastman, who worked as a bouncer for Silver Dollar Smith. Smith himself was a corrupt local politician and member of the Max Hochstim Association, also known as the Essex Market Court Gang due to the saloon’s proximity to the Essex Market Court. The Silver Dollar Saloon was notorious for housing Tammany Hall leaders, politicians and false witnesses, and Smith was reported to physically threaten local saloon owners in the neighborhood. In one such instance, Smith was arrested for stabbing August Gloistein, owner of a saloon on 354 Grand Street.

The Monk Eastman Story: From Gangster To Hero Doughboy

Eastman

There's also a very interesting site about a character who recreates the Monk Eastman

of the past

There's also a very interesting site about a character who recreates the Monk Eastman

of the past

"Halloween" 1901: A Scary LES Dude Of The Past: Monk Eastman

You wouldn't want to mess with Monk. Image by Pat Hamou. Pat has a great mobster site six for five and he sells his art work, very reasonably, on etsy

There's another story about Monk and the Silver Dollar Hotel/Saloon over at the Lower East Side History Project

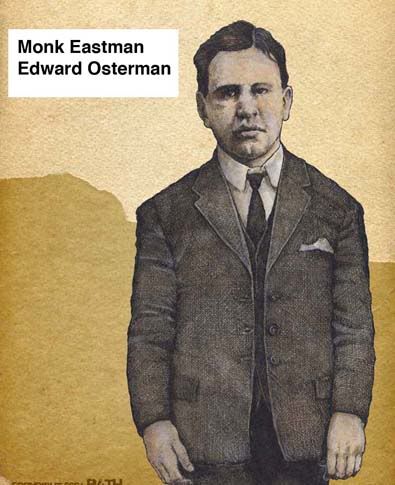

Monk Eastman, aka: Joseph Morris, William Delaney, Edward Delaney, etc., was born around 1873 in Brooklyn under the name of Edward Osterman. His parents were respectable Jewish restaurateurs and set Edward up with a pet store on Penn street, near their restaurant. Edward grew bored and soon abandoned his store for the excitement of street life, gangsters, prostitutes, stuss games and all of the ilk associated with it. However, Monk (Edward) always held an extreme fondness for cats and birds and he later opened up a pet store on Broome street. Monk trained a pigeon to sit on his shoulder while he went about his street travels and sometimes carried a cat with him. This "sensitive" trait contrasted sharply with his fondness for backjacking assignments and other violent deeds. Monk boasted that he had never struck a women with his club or killed one. When a lady suffered a severe lapse in manners, he blackened her eyes.

"I only give her a little poke, just enough to put a shanty on her glimmer. But I always takes off me knucks first."

Around 1895, Monk moved to lower Manhattan and established himself as Sheriff of New Irving Hall. The "Sheriffs" acted as armed bouncers and were responsible for keeping order (of sorts) in the social clubs or resorts that were frequented and owned by gangsters/politicians. Monk developed a patois of clipped, slangy speech and an indifferent dress style. The artist's rendition of Monk shows him at his best, usually only when he was before a magistrate. Monk became very popular with the hoodlums of the East Side and they began to imitate his slang and sloppy clothes. Monk's outfit usually consisted of a derby hat several sizes too small, a blackjack tucked into his pants, open shirt, and brass knuckles adorning each hand. He carried a large club and enjoyed using it, "sending so many men to Bellevue Hospital's accident ward that ambulance drivers referred to it as the Eastman Pavilion."

After a few years, Monk quit his position as Sheriff of New Irving and moved up the crime ladder towards gang leader. Monk had established his kingdom by 1900 with more than twelve hundred warriors under the Eastman banner. The Eastman headquarters was a dive on Chrystie street, near the bowery, where they stockpiled slung-shots, revolvers, blackjacks, brass knuckles, and other tools of gang warfare. Their main sources of income were derived from houses of prostitution, stuss games (a form of faro), political engagements, blackjacking services, and the operations of pickpockets, footpads, and loft burglars. Tammany Hall, the political power in New York City, frequently engaged the services of Eastman to bring in the votes at election time. In return, Tammany Hall lawyers bailed Eastman out whenever he got arrested.

Monk Eastman's feud with Paul Kelly began over a strip of territory between Mike Salter's dive on Pell street and the Bowery. Eastman claimed domain over the territory from Monroe to Fourteenth streets and from the Bowery to the East River. Paul Kelly and his Five Pointers believed that their kingdom included the Bowery and any spoils found in this area. Eventually, the constant feuding would cause the downfall of both Monk Eastman and Paul Kelly.

Wednesday, October 28, 2009

Saturday, October 24, 2009

Sidney Hillman

on excerpt from wikipedia. The last 4 paragraphs (bold-faced) mention the ILGWU/mob connection which Hillman tried to put a stop to after it had got out of hand.

Sidney Hillman (March 23, 1887 - July 10, 1946) was an American labor leader. Head of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America, he was a key figure in the founding of the Congress of Industrial Organizations and in marshaling labor's support for Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the Democratic Party.

Born in Zagare in Lithuania, Hillman left home to attend rabbinical school at age 14, but soon left school and became a member of the General Jewish Labor Union, a Jewish and socialist labor union within the Pale which the Czarist authorities tried to repress. After being arrested twice for political activity and spending several months in prison, Hillman fled the country in the wake of the suppression of the Russian Revolution of 1905, moving first to Manchester, England, and then in 1907 to Chicago.

Hillman found work there as an employee of Hart Schaffner & Marx, a prominent manufacturer of men's clothing. When a spontaneous strike by a handful of women workers there led to a citywide strike of 45,000 garment workers in 1910, Hillman was a rank-and-file leader in the strike.

That strike was a bitter one and pitted the strikers against not only their employers and the local authorities, but also their own union, the United Garment Workers, a conservative AFL affiliate. When the UGW accepted an inadequate settlement, the membership rejected the offer and continued the strike, winning some gains at Hart, Schaffner. Hillman became a business agent for the new local.

The leadership of the international union mistrusted the more militant local leadership in Chicago and in other large urban locals, which had strong Socialist loyalties. When it tried to disenfranchise those locals' members at the UGW's 1914 convention, those locals, representing two thirds of the union's membership, bolted to form the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America.

Hillman had taken the position of Chief Clerk within the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union in New York in early 1914. He found that job, in which he tried to maintain the stability imposed on a ferociously competitive industry by the Protocols of Peace, and in which the internal rivalries within the union threatened to flare up into all-out conflict, frustrating. When the insurgents who had walked out of the UGW convention to form the Amalgamated sent him a telegram imploring him to accept the Presidency—followed by another telegram from Bessie Abramowitz, one of the original leaders of the 1910 strike, an important figure in union politics and his fiance—he accepted and left the ILG after less than a year.

Hillman knew the risks he was taking. The AFL refused to recognize the new union and the UGW regularly raided it, furnishing strikebreakers and signing contracts with struck employers, in the years to come. He helped the Amalgamated solidify its gains and extend its power in Chicago through a series of strikes in the last half of the 1910s and to extend the union's membership into important garment centers in Baltimore and Rochester, New York, where the union had to overcome divisions within garment workers on ethnic lines and the opposition of the Industrial Workers of the World.

The ACWA also benefited from the relatively pro-union stance of the federal government during World War I, during which the federal Board of Control and Labor Standards for Army Clothing enforced a policy of labor peace in return for union recognition. Hillman was particularly receptive to the opportunities that government intervention in labor relations presented the union; he not only did not have the ingrained distrust of governmental regulation that now marked Samuel Gompers and other leaders of the AFL, but had a firm belief in the sort of industrial democracy in which government helped mediate between labor and management. The government's interest in maintaining production and avoiding disruptive strikes helped the Amalgamated organize non-union outposts such as Rochester and control the cutthroat competition that had prevailed in the industry for decades.

That policy ended in 1919, when employers in nearly every industry with a history of unionism went on the offensive. The ACWA not only survived a four month lockout in New York City in 1919, but came away in an even stronger position. By 1920, the union had contracts with 85 percent of men's garment manufacturers in the city and had reduced the workweek to 44 hours.

The ACWA pioneered a version of "social unionism" in the 1920s that offered low-cost cooperative housing and unemployment insurance to union members and founded a bank that would serve labor's interests. Hillman had strong ties to many progressive reformers, such as Jane Addams and Clarence Darrow, who had assisted the Amalgamated in its early strikes in Chicago in 1910 and New York in 1913. While other unions, notably the railroad brotherhoods and building trades unions within the AFL also founded banks of their own, the Amalgamated also used its banks to supervise the business operations of those garment businesses that came to it for loans.

Under Hillman's leadership, the union tried to moderate the fierce competition between employers in the industry by imposing industry wide working standards, thereby taking wages and hours out of the competitive calculus. The ACWA tried to regulate the industry in other ways, arranging loans and conducting efficiency studies for financially troubled employers. Hillman also favored "constructive cooperation" with employers, relying on arbitration rather than strikes to resolve disputes during the life of a contract. As Hillman explained his philosophy in 1938:

Certainly, I believe in collaborating with the employers! That is what unions are for. I even believe in helping an employer function more productively. For then, we will have a claim to higher wages, shorter hours, and greater participation in the benefits of running a smooth industrial machine....

Hillman's belief in stability as the basis for progress was coupled with a willingness to embrace industrial engineering approaches, such as Taylorism, that sought to rationalize the work processes as well. This put Hillman and the ACW leadership at odds with the strong anarcho-syndicalist tendencies within the union's membership, many of whom believed in direct action as a principle as well as tactic. On the other hand, it made Hillman receptive in the early 1920s to the Soviet Union's reconstruction efforts, particularly during its New Economic Policy phase. Hillman led the union into a joint business project with the Soviet Union that brought western technology and principles of industrial management to ten clothing factories in the Soviet Union.

Hillman's support for the Soviet experiment won him the enthusiastic support of the Communist Party USA in the early 1920s; it also further alienated him from those in the Socialist Party and associated with the Daily Forward under the leadership of Abraham Cahan, with whom Hillman and the Amalgamated already had strained relations. While Hillman's relationship with the Communist Party ultimately broke up in the conflict over whether to support Robert La Follette, Sr.'s candidacy for President on the Progressive Party ticket in 1924, Hillman never faced the sort of volcanic upsurge that nearly tore apart the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union during this period and never undertook the wholesale purges that David Dubinsky and other leaders of the ILGWU used to stay in power. By the end of the decade, after fighting and losing battles in Montreal, Toronto and Rochester, the CP was no longer a significant force in the union. While battling the CP, Hillman turned a blind eye to the infiltration of gangsters within the union. The garment industry had been riddled for decades with small-time gangsters, who ran protection and loansharking rackets while offering muscle in labor disputes. First hired to strongarm strikers, some went to work for unions, who used them first for self-defense, then to intimidate strikebreakers and recalcitrant employers. ILG locals used "Dopey" Benny Fein and his sluggers, who were more often hired by unions than employers although they were thugs for hire.

Internecine warfare between labor sluggers eliminated many of the earliest racketeers. "Little Augie" Jacob Orgen took over the racket, providing muscle for the ILGWU in the 1926 strike. Louis "Lepke" Buchalter had Orgen assassinated in 1927 in order to take over his operations. Buchalter took an interest in the industry, acquiring ownership of a number of trucking firms and control of local unions of truckdrivers in the garment district, while acquiring an ownership interest in some garment firms and local unions.

Buchalter, who had provided services for some locals of the Amalgamated during the 1920s. also acquired influence within the ACWA. One of his allies within the ACWA was Abraham Beckerman, a prominent member of the Socialist Party with close ties to The Forward, whom Hillman used to inflict strongarm tactics on his communist opponents within the union. Beckerman and Philip Orlofsky, another local officer in Cutters Local 4, made sweetheart deals with manufacturers that allowed them to subcontract to cut rate subcontractors out of town, using Buchalter's trucking companies to bring the goods back and forth.

In 1931 Hillman resolved to act against Buchalter, Beckerman and Orlofsky. He began by orchestrating public demands on Jimmy Walker, the corrupt Tammany Hall Mayor of New York, to crack down on racketeering in the garment district, Hillman then proceeded to seize control of Local 4, expelling Beckerman and Orlofsky from the union, then taking action against corrupt union officials in Newark, New Jersey. The union then struck a number of manufacturers to bar the subcontracting of work to non-union or cut rate contractors in Pennsylvania and New Jersey. In the course of that strike the union picketed a number of trucks run by Buchalter's companies to prevent them from bringing finished goods back to New York.

While the campaign cleaned up the ACWA, it did not drive Buchalter out of the industry. The union may, in fact, have made a deal of some sort with Buchalter, although no evidence has ever surfaced, despite intensive efforts of political opponents of the union, such as Thomas Dewey and Westbrook Pegler, to find it. Buchalter claimed, before his execution in 1944, that he had never had any deal with either Hillman or Dubinsky, head of the ILGWU. He did claim to have murdered a factory owner and labour opponents of Hillman at Hillman's behest, a claim which was never corroborated.

Friday, October 23, 2009

Garment Gangsters 2

portions of a 1914 nytimes article mentioning Benny Fein's use as a starker or strong arm for labor. Images are by Pat Hamou. Pat has a great mobster site six for five and he sells his art work, very reasonably, on etsy

portions of a 1914 nytimes article mentioning Benny Fein's use as a starker or strong arm for labor. Images are by Pat Hamou. Pat has a great mobster site six for five and he sells his art work, very reasonably, on etsya biography of Benny Fein

Benjamin "Dopey Benny" Fein (c. 1889-1962) was an early Jewish American gangster who dominated New York labor racketeering in the 1910s. With a criminal record dating back to 1900, Fein's arrest record included thirty charges from petty theft and assault to grand larceny and murder (of which he was acquitted twice due to lack of evidence). Fein was nicknamed "Dopey Benny" because of his eyes always being halfway-closed due to a medical condition.

Born in New York City, New York in 1889, Fein grew up in a poor neighborhood on Lower East Side becoming a petty thief and pickpocket as a child. A talented organizer Fein had formed his own gang of robbers in 1905 and during the next 5 years Fein would be sent to Elmira Reformatory several times particularly serving 3 1/2 years for armed robbery. Soon after his release in 1910 Fein joined "Big" Jack Zelig's organization soon becoming involved in labor union and extortion of the garment district. Fein also used his gang as labor sluggers, renting his gang out to either unions or companies, dominating much of New York's East Side eventually earning $20,000 a year. In 1913 several minor labor slugger gangs formed to break the monopoly held by Fein and rival Joseph Rosenzweig in which a large shootout took place on Grand Street and Forsyth Street lasting several hours, although few were killed, beginning the New York Labor slugger war which would last almost 4 years. Arrested for assault in 1914, Fein agreed to testify against several members involved in labor slugging when his political connections refused to help Fein resulting in the indictments of 11 gangsters and 21 union officials however none would be brought to trial. That same year Fein was again arrested for the murder of court clerk Frederick Strauss, who was killed in the crossfire during a shootout near St. Mark's Place, however he was later released when witnesses could not identify Fein at the scene. After his release in 1917 for labor slugging Fein's power had declined and by the end of the gang war, with Rosenzweig in prison for manslaughter, Fein decided to retire becoming a successful garment businessman.

In July 1931, appearing in court for the first time in 13 years, Fein was arraigned at Essex Market Court on felonious assault charges along with Samuel Hirsch and Samuel Rubin after throwing acid on local Brooklyn businessman Mortimer Kahn.

In 1941, Fein was arrested by detectives in a police raid ordered by District Attorney Thomas E. Dewey during which mobsters Abraham Cohen, John Ferraro and two Dallas businessmen, Herman Fogel and Samuel Klein, were also taken into custody after purchasing a recently stolen garment shipment valued at $10,000.

He and Cohen were named as the ringleaders of a criminal gang which, from armed robbery and burglary, took in an estimated $250,000 over a three-year period raiding the city's garment industry. Held in The Tombs until their trial, Fein was spared a mandatory life sentence for fourth time offenders and instead received a reduced sentence of ten to 20 years disappearing from public records sometime after.

Garment Gangsters

The Schmatta documentary doesn't touch on the gangster influence in the industry. Originally "good" mobsters were employed to counter the boss' use of mobsters to intimidate workers and break strikes. However, their influence soon transferred into control and ownership of several garment concerns, especially trucking. Little Augie and Benny Fein (mentioned in the article below) were part of that group. Benny Fein was mentioned before in April

Friday, October 16, 2009

More Early Gangs Of New York

from the book, The Road To Mobocracy What's being described is the rioting that was taking place in the 1820's and early 1830's. There's another reference to Fly (Vly) Boys, but it's a group very dissimilar to the one associated with the 1741 riots. The 1834 riots were mentioned here previously

mobcracy

mobcracy

Thursday, October 15, 2009

The Fly Boys Of 1741

from Gotham by Mike Wallace and Edwin Burrows The pages describe the events leading up to the executions in the common of 1741 pictured in the previous post.

Gotham Fly Boys

Gotham Fly Boys

Wednesday, October 7, 2009

27 Cherry Street: Nearby Now And Then

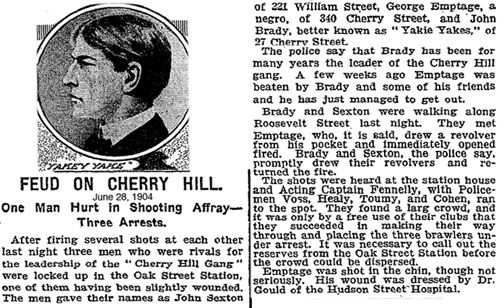

Above: Dover and Front Street in the early 1970's from a scene still of the French Connection. Below Cherry Hill Gang leader, Jake "Yakey" Brady, who lived at nearby 27 Cherry Street in the early 1900's

Labels:

french connection,

gangs of new york,

movies,

then and now,

Ward 4

Tuesday, April 21, 2009

239 Henry Street: Benny Fein

According to Ron Roth, Benny Fein was born here in 1889

from the six for five site

BENJAMIN FEIN aka DOPEY BENNY, 1889-1962

Dopey Benny acquired his nickname from an adenoidal condition, giving him a constant sleepy appearance. Another product of the Lower East Side, there was however nothing dopey about Benny. He had above average streets smarts and proved himself a visionary when it came to organizing the art of the shtarke, the strong-armed man. After a youth of stealing, pick pocketing and other petty crimes, his wayward habits caught up with him for awhile when was sent up to Sing Sing for armed robbery. Upon his release in 1910, he joined Big Jack Zelig's gang and it was during that period where he blossomed from just another street thug, exuding leadership qualities that he would later put to use.

That leadership in question fell into his lap after boss Zelig was shot and killed on a 14th St. streetcar. It was one of the many ripple effects that followed in the wake of the murder of gambler Herman Rosenthal, and the trial of Lieut. Charles Becker that followed it. Gang business could no longer operate in the same manner as it had in Zelig’s day, as there were too many prying eyes from every corner zeroing in on Lower East Side criminal activity. The corrupt nature of police and politicians and their affiliations to these gangs had been exposed, and some Tammany Hall members, once in bed with such gangs and rewarded handsomely, stepped back as well. Fein knew that the press coverage had been too hot on the Rosenthal – Becker affair and new angles needed to be figured out. While predecessors like Eastman and Zelig had dabbled in labor racketeering, Benny made it his first and foremost order of business and excelled at it. After all, he was the son of a tailor.

The Lower East Side garment industry was changing. Tenement sweatshops were giving way to factory - like production lines in buildings all around town up to 33rd st., and the industry was learning to meet the demands of a national marketplace. At the time, New York was producing the majority of clothing for the rest of America. Jews were at the forefront of this industry, as it was the one trade that they brought with them from Eastern Europe that helped them start a new life on these shores. Unions were set up early on to help the predominately Jewish labor force to make sure they were not exploited and working conditions were deemed satisfactory. At the forefront was the United Hebrew Trades (UHT), who in the past was not shy in relying on some of their own members to do a little intimidating with owners when needed. But after some time realized they would need to rely on some outside help for a little more persuading. Enter the gangster and his henchmen. Part of the problem in hiring whom some would deem ‘undesirables’ was there was never a guarantee they would work only for their side. Money motivated most of these men more than someone’s labor troubles, and reaping rewards from both sides of the conflict while it continued was a concern by the unions when hiring these gangs.

Benny Fein was different however. He was a man of principles. I like to think one particular event may of marked him significantly, and deeply affect they way he would conduct his business. On March 25, 1911 a fire broke out at the Triangle shirtwaist factory, housed in a building in Greenwich Village facing Washing Square Park. An unwatched, misplaced cigarette ignited a raging blaze that spread quickly within minutes, kindled by baskets of spare rags soaked in sewing machine grease and clothing materials. It consumed the upper three floors of the ten story building in less than ten minutes. Firemen at the scene were unable to conduct proper rescue operations, as their ladders just couldn’t reach past the sixth floor. Panic had set in for many of the trapped workers; most of them young women, and many of them Jewish. For unexplained reasons, some of the fire exits and doors leading to stairway exits and safety were locked or blocked. What crowds below at first thought were clothing bundles hurtling to the ground, soon realized the grim truth. Faced with the prospect burning alive, many watched in helpless horror from the street as some of the trapped workers started leaping, some holding hands with others, to their death nine and ten stories below. It was, and continues to be the worst workplace disaster in New York’s history. The death toll ended up at 146, and 123 of them were women, who worked more than fifty hour weeks in abhorrent working conditions. Despite unexplained locked doors, a fire escape that collapsed, and unsafe working conditions, Triangle’s owners were found not guilty of negligence in the trial that followed. District Attorney Charles Whitman, who was to be instrumental in the arrest and prosecution of Charles Becker had witnessed the building burn. So did Herbert Bayard Swope, the journalist who would print Herman Rosenthal’s story fifteen months later. I like to think Benjamin ‘Dopey’ Fein was one of those horrified in the crowd of thousands as well, helpless and angry, and vowing to try and make a difference.

"My heart lay with the workers." he was once quoted after refusing an offer of $15,000 to work on the manufacturer's side. He was unable to double cross his friends. His men, ‘shlammers’, broke heads only for the unions and under Benny they kept their loyalty. His operation was on the UHT payroll for four years. He also had ties to the ILGWU, the International Ladies Garment Workers Union. Dopey’s gang were given union cards as to picket alongside regular members so their actions seemed legitimate. He also was involved with the bakers’, butchers’, hat frame and neckwear workers, ragpickers’ and signpainters’ unions among others. Benny was busy. He almost single-handedly organized the practice of labor racketeering and thuggery into a full – fledged business. He drew up contacts and pay fees depending on the kind of slugging and ‘persuading’ that was needed by the unions. Instead of fighting, he created an elaborate system of territorial jurisdictions, delegating work to other gangs. Once contracted, he would sub-contract outside of the Lower East Side, somewhat unheard of in an underworld where most are motivated by greed and domination. Benny wasn’t dumb though. He still got his percentage on every sub-contract.

He also treated both sexes alike, giving equal pay for equal work, a very unusual practice back in the day. Because he used bats, clubs and blackjacks, though rarely guns, women were indispensable to him and served as ' toters' concealing weapons in mufflers, wigs, or a special hair-do of the day called the 'Mikado tuck-up'. Benny’s ladies encouraged nonunion female workers to join the unions with some intimidating practices as well. Of course, not all union members were happy with this scenario, after all, their demands were not always being met with legitimate manners, and a working relationship and trust between workers and employers could never be solidified completely. But, anytime anyone objected to their union’s strong - armed tactics, one of Benny's guerillas would warn them to keep quiet and avoid trouble. Not everybody was happy with Benny and his men, but many probably kept their jobs as a result.

Of course it wasn’t always smooth sailing for Fein and his gang. Rivalries with Italian labor racketeer Joe Sirroco led to many battles along Broome St and other areas. Dopey had led the way, building a monopoly, which was being continually challenged. Sirroco’s crew followed Dopey’s lead but in the other direction, working for the manufacturers. He also had a long running rivalry with Joseph ‘The Greaser’ Rosenzweig, and the labor slugging wars between these gangs would continue throughout 1913 and onwards. When an innocent bystander was shot and killed by accident after a botched set up by Dopey's men on Sirroco's troops, his power slowly began to decline.

Following numerous arrests, his last slip up was in the fall of 1914. Fein confronted and threatened to kill B. Zalamanowitz, a business agent for the butchers’ union who refused to pay Benny his $ 600 fee to protect his striking butchers, saying his job had been unsatisfactory. Zalamanowitz, panicked and frightened, called in the police prior to Dopey’s next scheduled visit. Waiting in the wings, they watched as Benny repeated his threats, and promptly arrested him on first-degree extortion charges. This was nothing new, a few hours in the Tombs and someone would come forward with the bail money, just like they always did, and Benny would be home by supper. But nobody came. Perhaps this time around the bail was too high at $ 8000, which the police had compounded from previous arrests. Maybe Benny was getting too hot for union officials to contiinue their affiliation and decided maybe the labor wars needed one less general. Benny sat and fumed. He felt double-crossed by everyone. Perhaps he had had enough. Benny finally broke down and began naming names. His organizational skills contributed to his thinking ahead, that this day may eventually come, and he had stayed one step ahead. Benny had written every single transaction down, unbeknownst to most of his associates. His testimony was a few hundred pages in length, explaining all the inner working of all the strike breaking gangs, and the unions involved. This led to many arrests of higher ups of both in the UHT and the ILGWU. Twenty -three labor leaders and eleven gangsters were charged with murder, extortion, assault, and riot in the months that followed. The man who designed the empire was able to tear it down as well.

Up until recently, crime historians had lost sight of him after the age of 26 and that last arrest, assuming he had disappeared into the city’s streets and never heard from again. But thanks in part to his grandson, Geoff Fein, the rest of Grandpa Dopey’s life has been brought to light a little bit more. While his 1914 testimony in exchange set him free, it would be a few more years before Benny would fly straight. He was arrested numerous times over the next few years, still active in the labor slugging trades, but in a smaller role. Benny probably didn’t make too many new friends after his testimony and it was probably much like starting over. He had a court appearance in 1931 on assault charges, his first in over thirteen years. Ten years later, Benny faced the courts again. He and fellow mobsters Abraham Cohen, John Ferraro, Herman Fogel, and Samuel Klein were taken into custody after a police raid caught them with a stolen garment shipment worth $ 10,000. He and Cohen were pegged as ringleaders in a gang responsible for over $ 250,000, 000 worth of stolen garments over a three year period. This would be his last trip to up Sing Sing, after being spared a mandatory life sentence. In the years following his release, Benny would stay in the garment industry, but on the legitimate side this time for good, applying his trade as a tailor, which he had learned from his father and had never forgotten. He made his life in Brooklyn and raised a family.

Benjamin Fein may have of walked a crooked line, and his actions deemed unjustifiable by most. But as a young man he was passionate enough to the cause of the worker, which he truly believed in, and was moved enough to try and do something about it. He was a rare breed of gangster; one spared a violent end on the streets, or in the electric chair. He passed away in 1962 from cancer and emphysema.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)