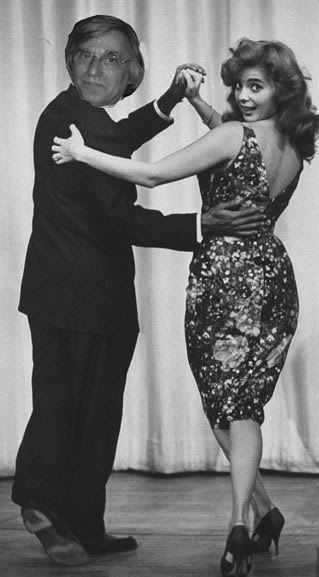

a video from the 1960's.

Abbe Lane (born December 14, 1932) is an American singer and actress.

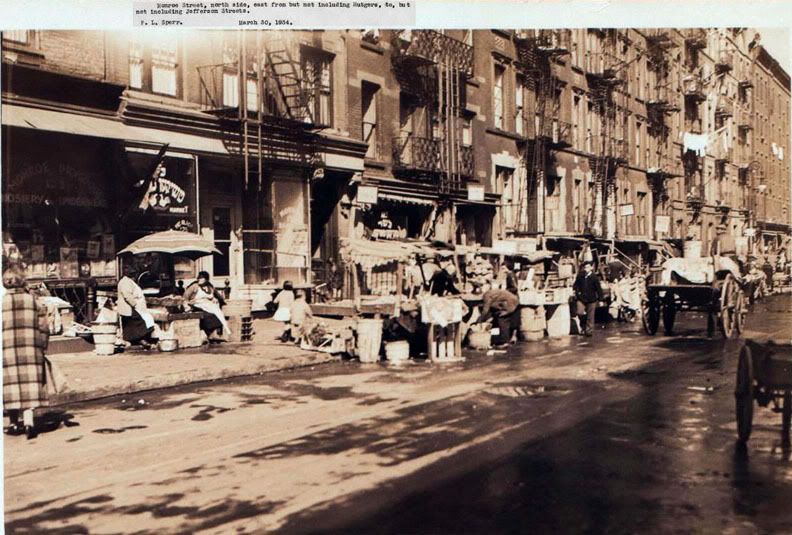

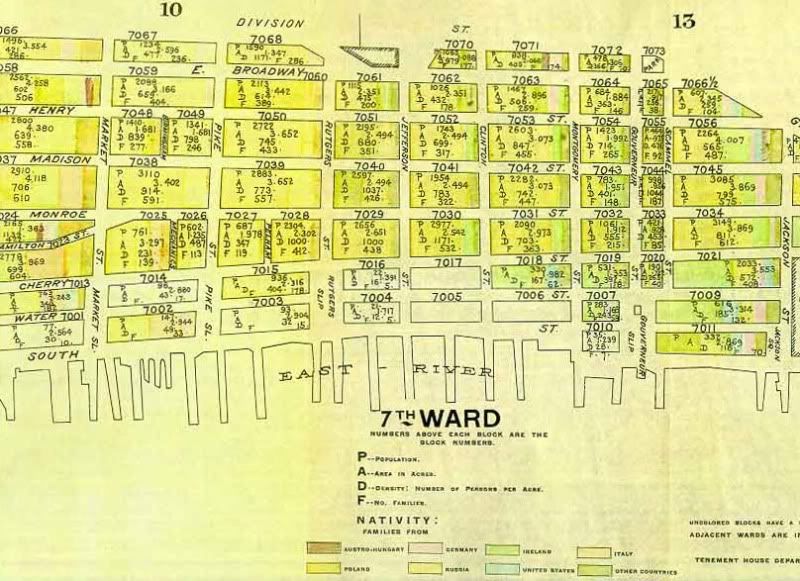

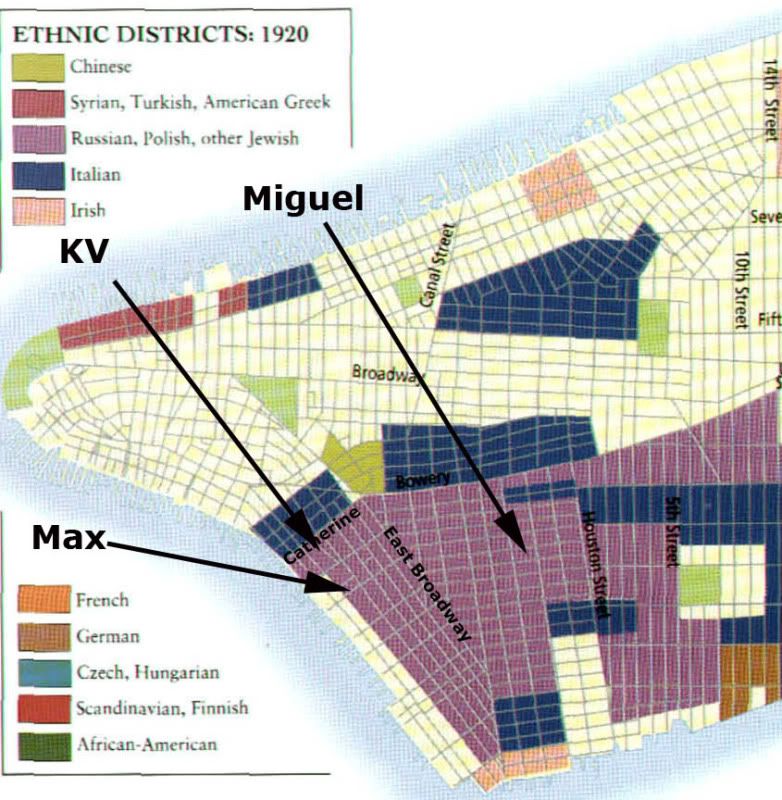

Born Abigail Francine Lassman to a Jewish family in Brooklyn, New York, Lane began her career as a child actor on radio, and from there she progressed to singing and dancing on Broadway. Quickly establishing herself as a "femme fatale", Lane found popularity in Italian films but was often criticized for her flagrantly sexual persona.[citation needed]

Married to Xavier Cugat from 1952 until their divorce in 1964, Lane achieved her greatest success as a nightclub singer, and was described in a 1963 magazine article as "the swingingest sexpot in show business". Cugat's influence was seen in her music which favored Latin and rumba styles. In 1958 she starred opposite Tony Randall in the Broadway musical Oh, Captain!. Unfortunately, her recording contract prevented her from appearing on the original cast album of the show. On the recording, her songs were performed by Eileen Rodgers. Lane later recorded her songs on a solo album. The most successful of her records was a 1958 album collaboration with Tito Puente titled Be Mine Tonight. Fans either didn't know or care that Abbe's roots were as far away from a Latin bombshell as a Jewish girl from Brooklyn could have. Apart from working solo, Lane would frequently make the talk show rounds with Cugat. After their break-up, Cugat would introduce his new wife/discovery, Charo.

She attracted attention for her suggestive comments such as "Jayne Mansfield may turn boys into men, but I take them from there", and also commented that she was considered "too sexy in Italy". Her costume for an appearance on the Jackie Gleason Show was considered too revealing and she was instructed to wear something else; however she appeared on the shows of Red Skelton, Dean Martin and Jack Benny without attracting controversy.

In addition to her Italian films, Lane was a frequent performer on the television show Toast of the Town during the 1950s. She also played guest roles in such series as The Flying Nun, The Brady Bunch (as cosmetics maven "Bebe Gallini"), Hart to Hart and Vega$. Lane fans got to see her once more in the 1983 film version of The Twilight Zone, in the role of an airline stewardess.

She has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame for her contribution to television, at 6381 Hollywood Boulevard.