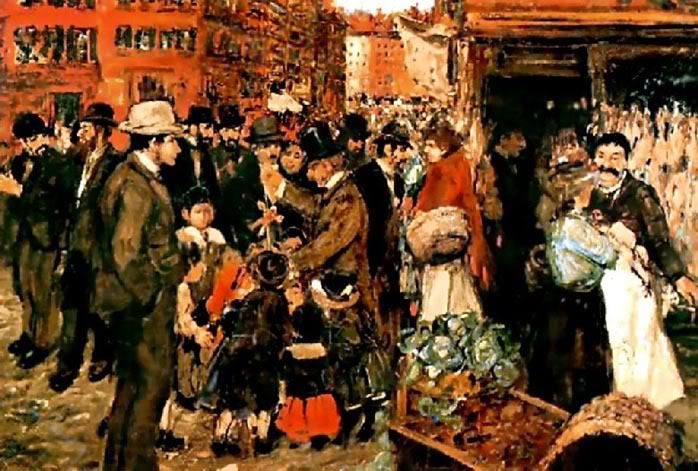

George Luks: Allen Street, 1905

from a nytimes review of a recent ashcan exhibit

Ashcan Views of New Yorkers, Warts, High Spirits and All

By KEN JOHNSON December 28, 2007

The painters of the Ashcan School just wanted to have fun. They chronicled the lives of poor city dwellers, but they were neither social critics nor reformers. Robert Henri, George Luks, John Sloan and other early-20th-century American realists identified with the group were high-spirited fellows who prided themselves on fielding a baseball team that regularly defeated those of the National Academy of Design and the Art Students League. They liked to dine in fancy restaurants and hang out at McSorley’s, the men’s-only tavern on East Seventh Street. They enjoyed the theater, the circus and trips to Coney Island. No Puritan crusaders, they were manly epicureans, and their virile hero was Teddy Roosevelt.

Such is the view propounded by “Life’s Pleasures: The Ashcan Artists’ Brush With Leisure” at the New-York Historical Society. Organized by James W. Tottis, associate curator of American art at the Detroit Institute of Arts, the exhibition presents more than 80 paintings by 22 artists dating from 1895 to 1925 that focus on scenes of recreation: bars and restaurants, sporting events, carnivals, parks and beaches.

The exhibition will not prompt any great re-evaluation of the Ashcan School. Its painters were not of world-class spiritual depth or formal imagination. But they were a lively bunch of provincial rebels who created America’s first true avant-garde, and their chapter in the book of art history is still fascinating.

The show also commemorates the forthcoming centenary of the exhibition that put the Ashcan School on the map: the 1908 show at MacBeth Gallery in New York called “The Eight,” which included Henri, Luks and Sloan, as well as William Glackens, Arthur B. Davies, Ernest Lawson, Maurice Prendergast and Everett Shinn. Henri organized the show to protest the rejection of himself and his friends from the National Academy of Design’s spring exhibition the previous year.

It was not until much later, however, that the Ashcan School got its name. In 1916 a staff member of the socialist magazine The Masses objected to the insufficiently high-minded “pictures of ashcans and girls hitching up their skirts on Horatio Street” by Sloan, George Bellows and others of the Henri circle that illustrated the magazine.

Elevated or not, the Ashcan painters were drawn to what they saw as the vitality of the lower classes. Bellows’s 1907 painting “Forty-two Kids,” in which a gang of mostly naked boys swims off a decaying Hudson River pier, is not an indictment of poverty but an anti-academic celebration of unsupervised freedom, spontaneity and play.

Favoring a brushy, gestural application inspired by the paintings of Hals, Velázquez and Manet, the Ashcan artists were action painters who mirrored the flux of reality with the flux of their brushwork, and, sometimes, by intensifying light and color. See, for example, Shinn’s extraordinarily luminous paintings of theatrical productions.

Many of the Ashcan painters were well prepared for this approach, having started out as newspaper illustrators. Being able to draw on the run, however, did not necessarily translate into very good painting. Ashcan paintings often look muddy and too hastily made.

Judging by an exhibition of his etchings at the Museum of the City of New York, Sloan, for one, was a better draftsman than painter. Most of the 34 prints in “John Sloan’s New York” are not much bigger than postcards, but teeming as they are with affectionate, finely detailed observations of old, young, poor and rich on sidewalks, in parks and on subways, they have a Dickensian amplitude.

This being America at the turn of the 20th century, sexuality tends to be muted, but it’s not totally repressed. One of Sloan’s most delightful prints shows a young woman descending subway stairs: Her skirt has flipped up in a sudden gust, giving a man going up the stairs a leggy eyeful. And back at the Ashcan show, there’s Henri’s bigger-than-life painting of a voluptuous model posing as a smirking Salome in a sparkly halter top, with bared midriff and sheer fabric revealing her naked legs; it was shocking enough in 1910 to be rejected from the National Academy’s spring annual.

Glackens’s sumptuous, Impressionist-style masterpiece, “Chez Mouquin,” intimates a socio-sexual complexity that is mostly missing from the rest of the show. The image of a beautiful, extravagantly dressed, sad-eyed young woman sitting in a restaurant with a beefy, prosperous-looking man in a tuxedo is like a scene from Edith Wharton’s “House of Mirth,” which, as it happens, was published in 1905, the same year as the painting was made. Alternatively, Guy Pène du Bois’s haunting, smoothly simplified, slyly satiric pictures of upper-class people in empty rooms could illustrate novels by Henry James.

In 1913 disaster struck the Ashcan School in the form of the Armory Show, which, by introducing European avant-gardists like Picasso, Matisse and Duchamp to America, caused the near-total eclipse of native realism.

If Ashcan painting looks like a dead end today, we should not forget that it gave birth to two indisputably great American painters: Edward Hopper and Stuart Davis. It might also be said that the Ashcan spirit returned in Abstract Expressionism, a movement that favored visceral action over aesthetic refinement. Willem de Kooning’s famous line — “I always seem to be wrapped in the melodrama of vulgarity” — could have been the Ashcan motto.

No comments:

Post a Comment