I was thrilled when I stumbled upon the information that a favorite author of mine, Leonard Michaels lived in Knickerbocker Village.

I was thrilled when I stumbled upon the information that a favorite author of mine, Leonard Michaels lived in Knickerbocker Village.From Wikipedia:

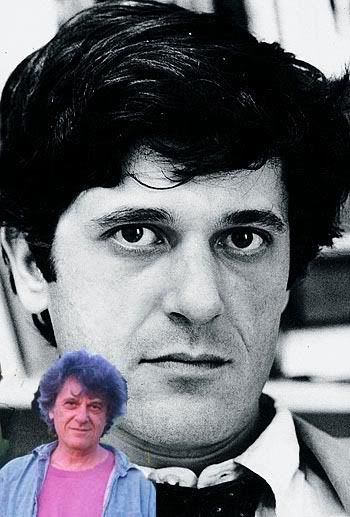

Leonard Michaels (January 2, 1933- May 10, 2003) was an American writer of short stories, novels, and essays. He was born in New York City and earned a B.A. from New York University and a M.A. as well as a Ph.D. in English Literature from the University of Michigan, before spending most of his adult life in Berkeley, California. Going Places, his first book of short stories, made his reputation as one of the most brilliant of that era's fiction writers; the stories are urban, funny, and written in a private, hectic diction that gives them a remarkable edge. The follow-up, coming six years later (Michaels was perhaps not prolific enough to build a widely popular career), was I Would Have Saved Them If I Could, a collection as strong as the first. The Men's Club, Michaels' first novel, is a story-like, relatively short comedic work that simultaneously attacks and celebrates the absurdities of men as they gather in a kind of urban support group. In 1986, the novel was made into a popular film, directed by Peter Medak, with the screenplay by Michaels, and starring Roy Scheider, Harvey Keitel, Stockard Channing and Frank Langella. Sylvia is a fictionalized memoir of Michael's first wife, Sylvia Bloch, who committed suicide. Michaels was a professor of English at the University of California, Berkeley. His son Jesse Michaels was vocalist in the seminal underground punk rock band Operation Ivy, a precursor to Rancid.

From the threepennyreview of 2003

When I was five years old, I started school in a huge gloomy Vic-torian building where nobody spoke Yiddish. It was across the street from Knickerbocker Village, the project in which I lived. To cross that street meant going from love to hell. I said nothing in the classroom and sat apart and alone, and tried to avoid the teacher’s evil eye. Eventually, she decided that I was a moron, and wrote a letter to my parents saying I would be transferred to the "ungraded class" where I would be happier and could play ping-pong all day. My mother couldn’t read the letter so she showed it to our neighbor, a woman from Texas named Lynn Nations. A real American, she boasted of Indian blood, though she was blond and had the cheekbones, figure, and fragility of a fashion model. She would ask us to look at the insides of her teeth, and see how they were cupped. To Lynn this proved descent from original Americans. She was very fond of me, though we had no conversation, and I spent hours in her apartment looking at her art books and eating forbidden foods. I could speak to her husband, Arthur Kleinman, yet another furrier, and a lefty union activist, who knew Yiddish.

Lynn believed I was brighter than a moron and went to the school principal, which my mother would never have dared to do, and demanded an intelligence test for me. Impressed by her Katharine Hepburn looks, the principal arranged for a school psychologist to test me. Afterwards, I was advanced to a grade beyond my age with several other kids, among them a boy named Bonfiglio and a girl named Estervez. I remember their names because we were seated according to our IQ scores. Behind Bonfiglio and Estervez was me, a kid who couldn’t even ask permission to go the bathroom. In the higher grade I had to read and write and speak English. It happened virtually overnight so I must have known more than I knew. When I asked my mother about this she said, “Sure you knew English. You learned from trucks.” She meant: while lying in my sickbed I would look out the window at trucks passing in the street; studying the words written on their sides, I taught myself English. Unfortunately, high fevers burned away most of my brain, so I now find it impossible to learn a language from trucks. A child learns any language at incredible speed. Again, in a metaphorical sense, Yiddish is the language of children wandering for a thousand years in a nightmare, assimilating languages to no avail.

I remember the black shining print of my first textbook, and my fearful uncertainty as the meanings came with all their exotic Englishness and de-voured what had previously inhered in my Yiddish. Something remained indigestible.

No comments:

Post a Comment