If you read through his autobiography you can see that his formative years were spent hanging out either in, or very close to, the Fourth Ward, as a newsboy and then as a teen reporter.

from Luc Sante

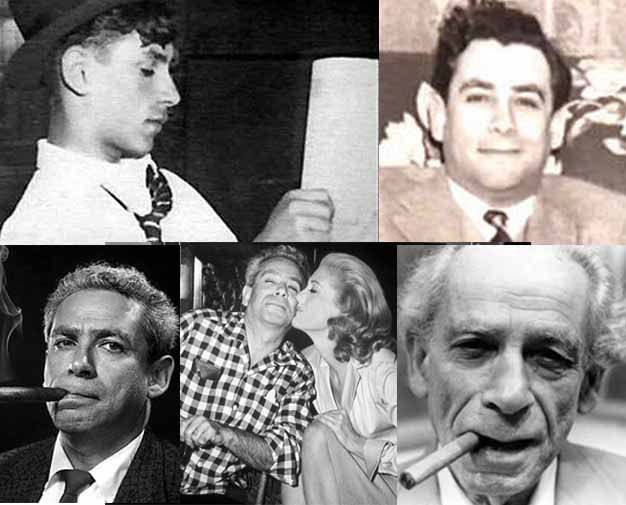

Samuel Fuller had ink in his veins, just like the hero of his 1952 newspaper epic, Park Row. After all, he started working as a copy boy when he was fourteen or so, and at seventeen he was the youngest crime reporter in the country, employed by the most daring and scurrilous tabloid America has ever seen, the New York Evening Graphic. When that paper folded (under the combined impact of a number of libel suits), he moved to California and soon began supplementing his salary by writing film scripts, selling his first in 1936, when he was just twenty-four. Five years later he was in the movie business full-time, and he directed his first picture, I Shot Jesse James, in 1949, not long after he got out of the service. In Hollywood he was clearly drawing on another part of his brain—he was a wildly visual and visceral filmmaker, and one of the great masters of the moving camera—but he never shed his reportorial instincts. He knew how to sell a story as well as tell one, how to hit hard and not let go. Every one of his movies has a built-in banner headline.

Pickup on South Street has a nominal subject as timely as any in the morning paper in 1952—PICKPOCKET HEISTS RED SPY MOLL––although today we might be more inclined to see it as PICKPOCKET FINDS LOVE, CHEATS DEATH. The Commie angle, besides being practically de rigueur for Hollywood that year, was a surefire means of injecting fear and trembling into the proceedings, by introducing a faceless, inhuman evil to contrast with the peccadilloes of the workaday American crook. That the picture is barely political can be demonstrated by the fact that, in France, where the Communist Party was a significant presence nobody wanted to offend, Pickup was released as Le Porte de la drogue—the villains became drug smugglers—with changes made only to the dubbed dialogue. What is at stake, after all, is nothing as high-flown as The American Way (“Are you waving the flag at me?” pickpocket Skip McCoy asks the FBI agent grilling him); rather, it is the possibility of a force so morally alien that, like the child molester in Fritz Lang’s M, the law and the underworld can be united, however briefly, against it.

McCoy is played by Richard Widmark, whose face could illustrate the dictionary definition of insolence. One look at him and you don’t even need the backstory to know why the cops want to send him up the river for good. Although he went on to play a wide variety of characters in his career, he was initially typed by his screen debut, which was also his first starring role, in Henry Hathaway’s Kiss of Death (1947), in which he kicks an old lady down the stairs. Here it is the old lady who nearly does him in, although their relationship is complex—she is, for all dramatic intents and purposes, his mother. Playing the part is the inimitable Thelma Ritter, who was unsurprisingly nominated for an Oscar for the role (it was the fourth of her six nominations in a twelve-year span; she never won). Ritter, only nine years older than Widmark, took the stereotypical Apple Annie character and over the course of her career made a Russian novel out of it. Here she is pathetic, cold-blooded, kittenish, stalwart, cunning, and tender, sometimes all at once. The love interest is supplied by Jean Peters, who is awe-inspiringly ripe—you imagine wardrobe having to gaffer-tape her dress every morning, to keep her from bursting out of it. Peters may not have been the greatest line-reader who ever lived, but she exudes sex so palpably, you can smell the pheromones. (She lost the fifties erotica sweepstakes to the forces of blondeness, alas, and gave up and married Howard Hughes.)

The locations are few but well chosen. A street, a subway station, a Chinese restaurant, a precinct-house office, an apartment (with that forgotten urban-thriller resource, the dumbwaiter)—put them together and presto! you have New York City and its teeming masses. Richard Widmark’s home is something else again, though: a bait-and-tackle shack on stilts, connected to South Street by a swinging bridge. It seems like a preposterous idea today, when New York’s function as a port has been all but erased, but (although I could almost swear I’ve seen a Berenice Abbott photograph of it from the 1930s) it was close to preposterous then, too. The shack is a bubble cantilevered off the tip of the material world, the bridge leading to it passing through the wall of sleep. In the midst of a zillion urban-grit signifiers, the shack cues viewers to the numerous fantasy elements of the story, not least the Red spy subtheme, but also the crooks themselves, who come from The Threepenny Opera by way of Damon Runyon. The shack is the beyond, but given that it is a real shack, roughly carpentered and battered by weather, it is also—what might be Fuller’s heraldic device—the embodiment of contradiction.

Fuller is crude and subtle, blatant and deep, unschooled and spilling over with ancient lore, harsh and plaintive, cynical and so attuned to complicated human emotions, you can’t accuse him of being merely sentimental. Pickup on South Street, it follows, is a penny dreadful with a hundred layers of felt meaning—the kind you register subcutaneously, without requiring professors to dissect and explicate it. If film noir is a genre in which tin-pot crimes are merely the outer manifestations of the churning unconscious, then Pickup on South Street is quintessential noir. Like so many of the worthwhile products of the American 1950s, it is a work of reverberating complexity, wrapped up to look like a candy bar.

No comments:

Post a Comment