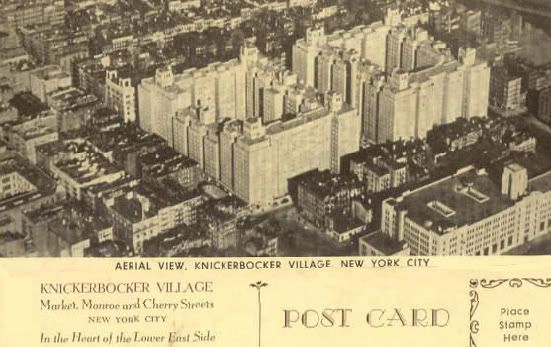

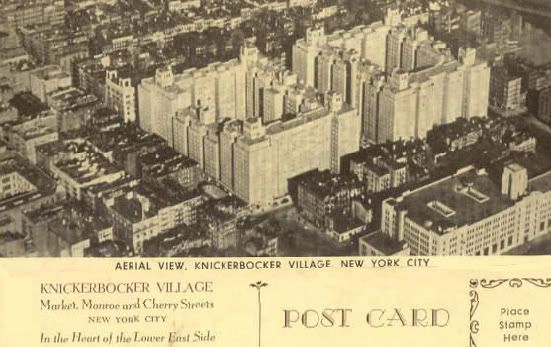

Here's the Lopate piece referred to on the previous post. I figured I'd use it to offset these misc images of KV that needed a "home" The first is a still that I captured I think from the 1948 film noir classic, "Naked City." I don't know why McCourt used KV as a background for "Tis." I'm pretty sure he didn't live there.

A block or so north of the Brooklyn Bridge, just behind the old New York Post Building, between Catherine and Market Streets, squats Knickerbocker Village. This unassuming enclave of bare brick apartment towers, privately managed, which might easily be mistaken for one of the nearby government projects, made history as the first major housing development even partially supported by public funds. Though currently in scale with everything around it, it seemed huge when it opened in 1934, "a blockbuster," according to the AIA Guide to New York City, which added that "It maintains its reasonably well-kept lower-middle-class air today." The other historical significance of Knickerbocker Village is that it stands on the same site as the notorious Lung Block, which it obliterated.

Whenever we are tempted to bemoan the monotony of these brick high-rise compounds that dominate the riverbanks of the Lower East Side, we might stop for a moment and think about all the Lung Blocks that used to populate the site.

Ernest Poole, the journalist and novelist of The Harbor whom I discussed earlier, wrote journalistic exposés about the Lung Block, which had the highest tuberculosis incidence of any street in the city. Poole was part of a circle of idealistic young reformers (including Isaac N. Phelps-Stokes, who later wrote the monumental study, The Iconography of Manhattan Island) trying to raise a moral outcry about housing conditions in the Lower East Side. In The Bridge, his 1940 memoirs, he describes how he went down to the Lower East Side in 1902:

"The Lung Block, as I named it then, was far down on the East Side near the river. In early years, when that quarter was a center of fashion in our town, many of the buildings had been great handsome private homes, but long ago they had been turned into grimy rookeries, the spacious rooms divided into little cell-like chambers, many only stifling closets with no outer light or air. I can still smell the odors there. In what had been large yards behind, cheap rear tenements had been built, leaving between front and rear buildings only deep dank filthy courts. Nearly four thousand people lived on the block and, in rooms, halls, on stairways, in courts and out on fire escapes, were scattered some four hundred babies. Homes and people, good and bad, had only thin partitions between them. A thousand families struggled on, while many sank and polluted the others. The Lung Block had eight thriving barrooms and five houses of ill fame. And with drunkenness, foul air, darkness and filth to feed upon, the living germs of the Great White Plague [tuberculosis], coughed up and spat on floors and walls, had done a thriving business for years."

Poole vividly described a young, tubercular Jew, near death, crying out for more air. The paradoxical proximity of the Lung Block to the expansive, world-connecting river was also noted: "There was a huge Danish woman too, on the Lung Block, who became my friend. Sailors came and stayed with her, 'deep-water' sailors, by which I mean that they shipped on voyages around the Horn to Singapore and Shanghai and other fascinating ports. As gifts or loans when they sailed away, they had left a lively marmoset, a scarlet parrot, heathen idols, painted shells and other things that pulled my thoughts out of the stinking rooms near by and sent them careering far off over the Seven Seas. I sometimes felt the Wanderlust and, in those lovely days of spring, wandered along the East River piers where lay the last of the ships with sails, listening for 'chanteys' of their crews as they heaved on the ropes and slowly, slowly the big ships moved out on the river, bound by the sea. But from such whiffs of the ocean world back I would dive into the Lung Block, all the more bitter that human beings should be choked to death in such foul holes, when there was so much fresh air and health and sunlight so close by."

Poole went to work, writing up the horrors in strong muckraking fashion. A radical friend, scoffing at the notion that the pen was mightier than the sword, told him: "What the Lung Block needs is the ax." (Later, Robert Moses would similarly remark: "when you operate in an overbuilt metropolis, you have to hack your way with a meat ax.") Undaunted, Poole shouldered on: "My report was featured in the press. Reporters came to write up the block. I took them around, with photographers. Hearings were held up at Albany. I gave my testimony there. So we raised hell with the politicians, and at twenty-three I thought that our campaign would succeed. I was wrong. For the landlords on the Lung Block had many influential friends. So came delays, delays, delays, until in the papers the story grew cold. It took thirty-two years to bring the ax. It came at last, under the New Deal. The rotten old block was razed to the ground and in its place you may see today the airy sunny apartment houses of Knickerbocker Village."

Fred C. French, the same developer who had built Tudor City a few years earlier (1925-31), put together Knickerbocker Village, which, completed in 1933, housed 4000 persons on five acres in twelve-story blocks around inner courts. During the Depression, the federal government had made available a small pot of funds for private developers nationwide to clear slums and construct housing developments in their stead, based on a set of guidelines regarding building standards and occupational density. French had to travel to Washington over fifty times, hat in hand, to get an $8 million loan from the federal government's Reconstruction Finance Corporation for the housing development. The sticking-point was the government's objection that the complex had a density at least double that recommended by federal guidelines, but which the developer argued was needed for a satisfactory investment. In the end, the government agreed. French, who was both public-spirited and profit-minded, (French told some impressed Princeton students in 1934: "Our company, strangely enough, was the first business organization to recognize that profits could be earned negatively as well as positively in New York real estate--not only by constructing new buildings but by destroying, at the same time, whole areas of disgraceful and disgusting sores." [Quoted in Max Page's The Creative Destruction of Manhattan] ) helped offset the costs for buying the land and developing Knickerbocker Village in two ways: first, by raising the density of land use through taller apartment towers, and second, by replacing low-income tenants with middle-income households. (This same strategy would be followed later by the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, which tore down another chunk of the Lower East Side along the river to build Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village).

There is certainly an argument to be made for the state helping middle class, white-collar workers in urban areas defray housing costs. Less valid was the argument employed that by subsidizing new housing for the middle class, you would then free up thousands of units for rental by low-income tenants. The trickle-down theory, applied to housing, proved as faulty as elsewhere, since rents in the vacated apartments were still beyond the reach of the poor. The effect of slum clearance on its inhabitants was thus to push them into new slums, as Anthony Jackson showed in his study of Manhattan low-cost housing, A Place Called Home. "When 386, mostly Italian, families had been forced to leave the old 'Lung Block'…to make way for Knickerbocker Village, four-fifths of them moved into other nearby tenements. At Stuyvesant Town, a survey showed that roughly three-quarters of the 3000 displaced families would move into other slums."

Not everyone saw the slums on the Lower East Side as blight. Jimmy Durante, the entertainer, who grew up in the Lung Block ward, reminisced to Joseph Mitchell about a time "'when the East Side amounted to something'….Sitting there in the dark theater, nursing his hangover, the big-nosed comedian began to talk about his childhood, the days when he used to run wild on Catherine Street, raising hell with the other kids, the days when he liked to go barefooted and they had to run him down and catch him every winter to put shoes on him…" Like most children who were reared in slums, he had a slightly different perspective than the housing reformers. "'We kids used to have a good time,' he said. 'They tore down where my home was and where my pop had his [barber] shop. They tore it down to put up this high-class tenement house, this Knickerbocker Village. Most of the old-timers moved out long ago."

There was, it seems, in the insular poverty of the Lower East Side, a yeasty substance breeding ambition along with despair. You have only to read the charged memoirs of Anzia Yezierska's Red Ribbon on a White Horse or Mike Gold's Jews Without Money, both writers from the Lower East Side, to sense their pride in the ghetto they were so desperate to escape. The emotional glue that bound the tenement-dwellers to the Old Country dissolved when the rickety buildings were demolished and replaced by anonymous, modern high-rises. As Alfred Kazin wrote about a similar urban renewal, ''despite my pleasure in all the space and light in Brownsville…I miss her old, sly and withered face. I miss all those ratty little wooden tenements, born with the smell of damp in which there grew up so many school teachers, city accountants, rabbis, cancer specialists, functionaries of the revolution, and strong-arm men for Murder, Inc."

Some of the nostalgia of Kazin and Durante for slum-bred ambitions seems in retrospect a disguised ethnic boasting. The ghetto may have proven a launching-pad for Jews and Italians to reach the middle class by the second generation, but it was not having the same catapult effect for the Hispanics and African-Americans who had taken their place. The new, nonwhite poor were in no position to organize protests at the razing of tenements, nor were they necessarily as attached to them as previous groups had been.

Thus, Robert Moses had a point in scoffing at the notion that "since the slums have bred so many remarkable people, and even geniuses, there must be something very stimulating in being brought up in them." But the more debatable point was Moses' leap from asserting that the "slum is still the chief cause of urban disease and decay," to contending that its "irredeemable rookeries" had to be eradicated. It takes a certain literalism to go from deploring the disease and crime in a poor neighborhood, to indicting the very buildings themselves as criminals. After all, the hovels that comprised the Lung Block had begun their existence in the early nineteenth century as respectable houses for well-off families; only later were they were subdivided and rented to the poor at unspeakable densities. Current medical science suggests that even the Lung Block buildings might have been spared--given a good disinfectant cleaning and spruced up, their rear tenements removed for better light and ventilation--and restored to salubrious respectability. But that is not how it appeared to most social reformers of the day (including those far more committed to helping the poor than Moses): they hated the suffering they witnessed in the tenements so much that they came to blame the very mortar, bricks, staircases, walls. Having invoked so often the metaphors of pathology (slums were described as "cancerous," "pestilential," "abscessed," "a tumor," "puss-filled,"), it seemed the most sensible course to call for their surgical removal.

Among the lower-middle-class strivers attracted to Knickerbocker Village were Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, who moved into a three-room apartment in the spring of 1942. They paid $45.75 a month for their river-view, eleventh-floor accommodations, and made use of the project's nursery school and playground after they had children, and it was there, the bulk of evidence now suggests, that Julius conspired with Ethel's brother, David Greenglass, to spy for the Soviet Union.

Knickerbocker Village had one of the strongest and most insurgent tenant unions in the city, the Knickerbocker Village Tenants Association (KVTA). In 1947, when the landlord, French, tried to raise the rent twelve percent and evict tenants who exceeded income limits, KVTA waged a campaign against him in the press and the courts, vowing a rent strike as well. I like to picture Julius going to these meetings and putting in his two cents' worth, though he probably regarded such local efforts as trivial, compared to stealing atomic secrets.

If you grew up in a Jewish ghetto in the 1950s, as I did, you could not escape the Rosenberg case. Newspaper photographs of Ethel in her mouton coat and upswept coif looked strikingly like my mother. In fact every other woman in our neighborhood looked like Ethel: dark-eyed, pudgy, scared, self-righteous and exalted with ideals of social justice. We felt personally imperiled by the Rosenbergs' persecution, removed as we were by less than a few degrees of separation. When my mother joined a fight to have a traffic light installed in front of our nursery school, many of her fellow-protestors were Communists. She became friends with these Party members, up to a point, but then they bored her by turning every conversation into a political harangue. Never mind the millions of kulaks slain by Stalin, or the Moscow Show Trials; my mother didn't like Communists because they violated the rules of conversation. No one in my family, to my recollection, ever maintained the Rosenbergs' innocence; if anything we assumed they were guilty, but thought they shouldn't be executed because the secrets they stole were probably small potatoes, and because capital punishment was wrong.

My Aunt Minna was a Communist: when my brother and I stayed one summer with her in California, she would get apoplectic as soon as anyone appeared on television who had named names. Lloyd Bridges in Sea Hunt? "He sang. Change the channel!" I thought of Communists as a slightly cracked set of familiars, character actors left over from the Yiddish theater, admirably wanting to make the world a better place, but rigid in their refusal to consider opposing facts. Who knows whether I might have joined the Party had I grown up in the Thirties instead of the Fifties? By the time I started college, in 1960, JFK was off to the White House, Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. was advising him, and the Communist Party no longer counted, except as a joke. My mother told me: "If you're ever on unemployment insurance and they send you to interview for a job you don't want, just bring along a copy of The Daily Worker."

In one of the best New York waterfront movies, Samuel Fuller's Pickup on South Street (1953), a number of key scenes were set a stone's-throw away from the Rosenberg’s apartment, on a South Street pier. Coincidentally, it revolved around a plot by Communist spies to steal government secrets. "If you don't cooperate," the FBI agent tells the cynical hero, "you'll be as guilty as those traitors who gave Stalin the A-bomb."

Our hero, or anti-hero (played by Richard Widmark) is a pickpocket who hides out in an abandoned bait shack, perched on pilings in the East River, and reached only by a flimsy catwalk. The atmospheric night scenes prove again that the waterfront and film noir make an irresistible combination. Through the shack window we glimpse the Manhattan Bridge, and a dependably passing tugboat or barge (courtesy of rear view projection, since the film was really shot, for the most part, in California ).

The great supporting actress Thelma Ritter gave the film's most memorable performance as Moe, an aging necktie-peddler and stool pigeon in a tired flower-pint dress, who is saving up for a fancy funeral. She tells the threatening Communist agent, Joey, in her weary Brooklyn accent: "Look, mister, I'm so tired, you'd be doing me a big favor, blowing my head off." Moe and the Rosenbergs: both from the same New York working-class milieu, striving to reach the lower-middle-class; both doomed to a premature, unnatural death by the Cold War.

Apparently Julius and Ethel felt cramped in their small apartment in Knickerbocker Village, after their two children were born. I stare up at the nondescript brick towers, and wonder what they would have thought about the transformation of the Lower East Side in our day. They did not live to see the particular horror of 1960s "urban renewal," with its wholesale destruction of neighborhoods deemed slums, and its displacement of the working poor. Gentrification, which began later, in the 1980s, probably displaced as many poor tenants in the long run as did urban renewal, but it had a gentler effect on the streetscape--indeed, preserving what might otherwise have crumbled into dust. Those surviving parts of the Lower East Side's old tenement environment that survived have seen their housing stock slowly improved and renovated through gentrification for the past twenty years, while playing host to bohemian cultural activities and chic little boutiques: not so bad a fate for the old ghetto, all things considered.

The esplanade gives out, and becomes an inhospitable parking area and repair shed for city sanitation and fire department trucks. So I cross over to the inland side. One public housing complex after another: The Rutgers Houses, Laguardia Houses, Two Bridges, Vladeck Houses, Corlear's Hook Houses. The one architectural standout is Gouverneur Court, which used to be the old Gouverneur Hospital. It has those magnificent red-brick rounded bays with black wrought-iron balconies that I've often admired in a car from the FDR Drive. Now I'm seeing it at street-level and it's quite impressive. A plaque informs me it was built in 1898, and is now on the National Register of Historic Places. Its red sandstone has wonderful carved ornamental detail. Surprisingly, it was not turned into expensive condos, but preserved, under a deal brokered by then-Mayor David Dinkins, for lower-income occupants (the management sign says "Affordable Housing for NYC.")

An affable, proprietary tenant in blue shorts, with incredibly thick glasses, who looks like he hangs out often in front, seeing my curiosity about the building, tells me, "It's all single-room apartments. Section 8." Section 8 is a Federal program that provides subsidies for impoverished, often elderly people, or people on disability.

"It's beautiful."

"You should see the courtyard."

"I'd like to," I say. "Can you take me in for a moment?"

"Nah. You can't go into Gouverneur House without photo ID. They're very strict about it."

Just then another tenant, a middle-aged woman in shorts and curlers, comes out of the building. "Hey Denny, want some coffee?"

"Nah. I never had a taste for it. I get all my caffeine from Coca Cola."

"It's getting cold."

"September, it's all over. You won't be able to wear shorts no more."

"I went to the doctor, they say it's a heat rash. I was afraid it's diabetes. Everyone I know got diabetes."

"You'll be okay."

"You're a saint, Denny," she waves at him, and walks away. He nods: Saint Denis. He continues to guard the steps, looking out across at the stern Vladeck Houses, angled all different ways. I head back towards the East River, to try to pick up a navigable walking trail along the waterfront

Here's the Lopate piece referred to on the previous post. I figured I'd use it to offset these misc images of KV that needed a "home" The first is a still that I captured I think from the 1948 film noir classic, "Naked City." I don't know why McCourt used KV as a background for "Tis." I'm pretty sure he didn't live there.

Here's the Lopate piece referred to on the previous post. I figured I'd use it to offset these misc images of KV that needed a "home" The first is a still that I captured I think from the 1948 film noir classic, "Naked City." I don't know why McCourt used KV as a background for "Tis." I'm pretty sure he didn't live there.

No comments:

Post a Comment