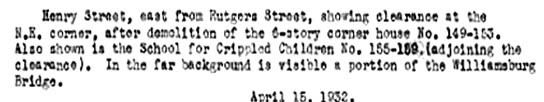

Here's Moe Fishman speaking at a convention in 2006. He passed away last year

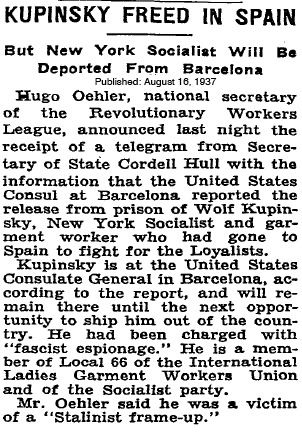

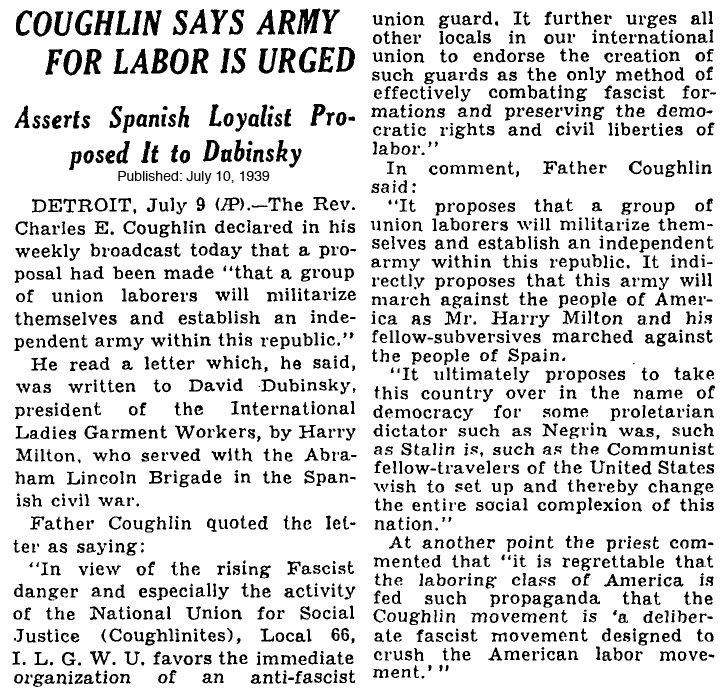

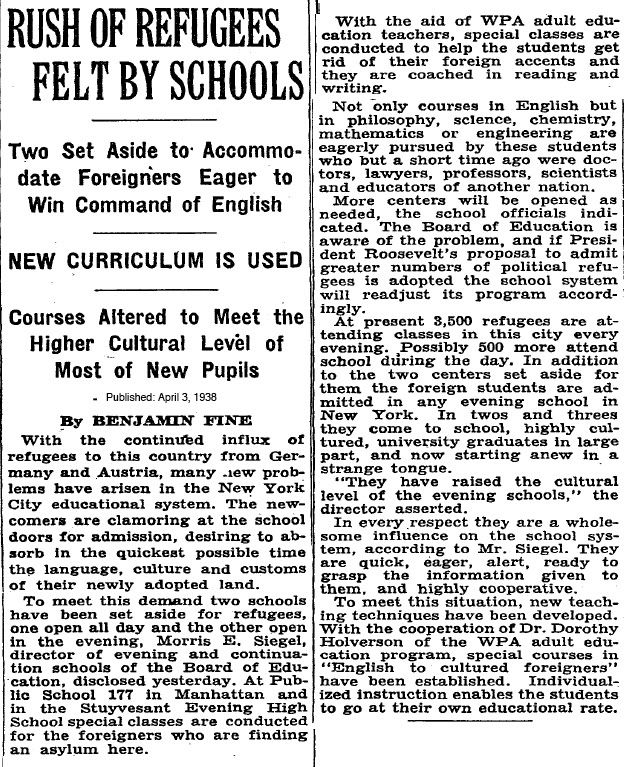

August 12, 2007, Moe Fishman Dies at 92; Fought in Lincoln Brigade

By DOUGLAS MARTIN

Moe Fishman, who as a 21-year-old from Astoria, Queens, fought Fascists in Spain with the Abraham Lincoln Brigade and was severely wounded, then led veterans of that unit in fighting efforts to brand them as Communist subversives, died on Aug. 6 in Manhattan. He was 92.

The cause was pancreatic cancer, said Peter Carroll, chief of the board of governors of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives.

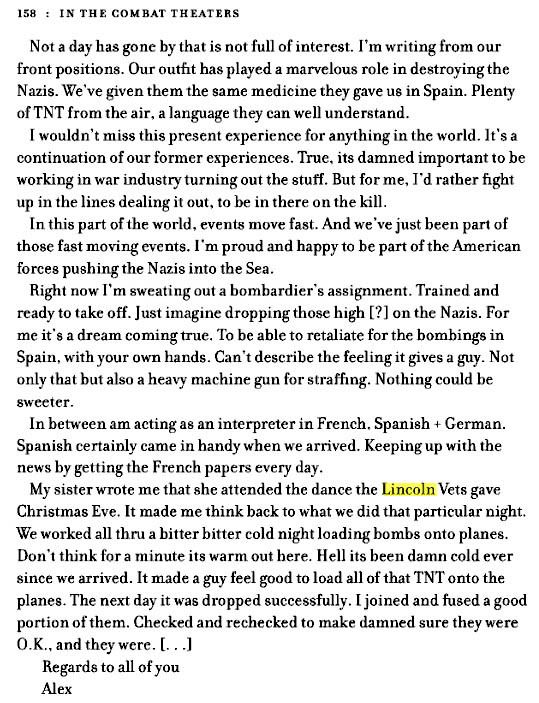

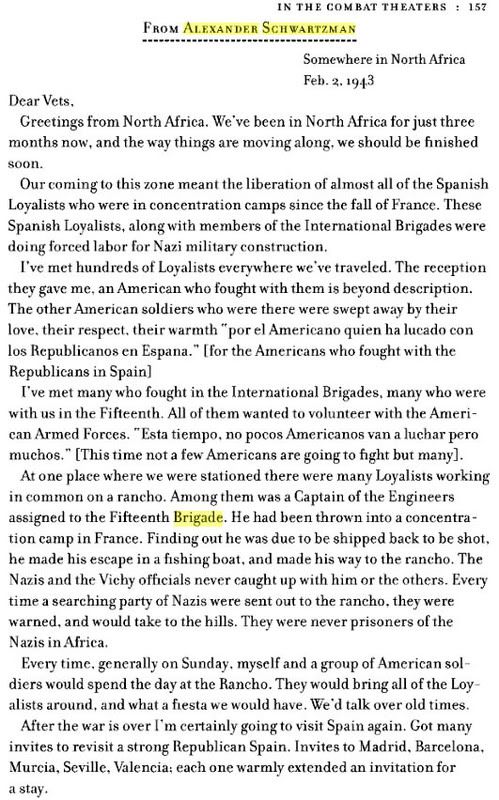

Mr. Carroll said that about 40 of about 3,000 American veterans of the Spanish Civil War volunteers are living. It had been the job of Mr. Fishman, as executive form the XV International Brigade.

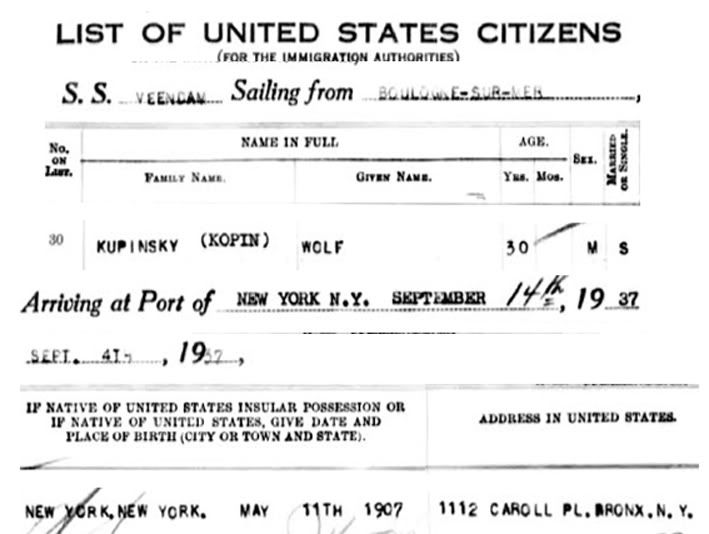

In 1937, Mr. Fishman was a college dropout working in a laundry and driving a truck. He was also a member of the Young Communist League, having joined partly to meet like-minded young women at dances the organization sponsored, he said in an interview with The New York Times in 2004.

He also liked how the Communists responded when a family behind on the rent was evicted and thrown on the streets with its furniture. He told The Times that party members would use an ax or hammer to break the lock on the door and put the family back in.

Many believe that at least half of the volunteers for the Lincoln Brigade were Communists, but Mr. Fishman’s reasons for joining were more complex, he told The Times in 1969.

“Why did I go?” he said. “That’s hard to say. That’s a key question. I was active in trade union work. I wanted to travel. I belonged to the 92nd Street Y.M.H.A., and we were very anti-Fascist, much opposed to Hitler, Franco.”

He was born Moses Fishman on Sept. 28, 1915, and grew up in Astoria. On the day he was to depart for Spain, he left for work at the usual time to deceive his parents. Halfway down the stairs, he realized he had forgotten his toothbrush, returned for it and broke it in half so it would fit in his pocket. (It was the only thing he brought back from Spain, he told The Hartford Courant in 2000.)Mr. Fishman called his parents when he got off the subway near the dock, and they cried when he told them his plans. His mother had never seen his father cry. He himself was unafraid. “When you’re 21, there’s no bullet meant for you,” he told The Times in 2000.

On July 5, 1937, during the Brunete offensive west of Madrid, a sniper hit Mr. Fishman’s thigh, leaving 32 pieces of bone and metal. He spent a year in Spanish hospitals, and a pin was put into his leg. At one point the leg became infected, he told The Courant. He was then in and out of hospitals in the United States for two years.

During World War II, Mr. Fishman was in the merchant marine. Afterward, he and other Lincoln veterans became involved in aiding refugees from Franco’s Spain. President Harry S. Truman’s attorney general labeled the veterans group subversive. In 1950, when such organizations had to register with the government, the entire executive committee of the Lincoln Brigade veterans resigned. Mr. Fishman stepped in to become secretary-treasurer.

After a federal court removed the subversive label in the 1970s, Mr. Fishman wrote a colleague that the change might not be good. He wryly suggested doing something subversive so as not to appear irrelevant to rebellious youth. (Mr. Fishman later dropped his party membership, Mr. Carroll said.)

Mr. Fishman is survived by his partner, Georgia Wever, of Manhattan, and his sisters Lilly Litsky, of Santa Cruz, Calif., and Pearl Fishman, of Yonkers.

He never tired of a lively demonstration. But he came to prefer sitting in a folding chair, as he did in 2004, when he hailed protesters at the Republican National Convention in Manhattan. When they saw his Lincoln Brigade banner, they applauded back. In an interview with The Villager, a neighborhood newspaper, he said, “They come up — these young girls — they want you to take a picture with them and they kiss you.”

Other late-life adjustments were harder. In 2001, an article in The Economist recounted how he stumbled over the word “globalization” at a protest against globalization. “It was so much easier to say when we called it imperialism,” he was reported to have said.

Correction: August 30, 2007

An obituary on Aug. 12 about Moe Fishman, a veteran of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, Americans who fought in the Spanish Civil War, referred incorrectly to his high school education. He was a graduate of Stuyvesant High School in Manhattan; he did not drop out. (He later dropped out of City College, primarily for financial reasons.)

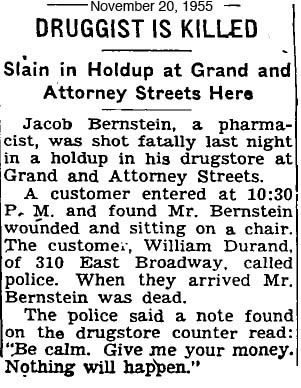

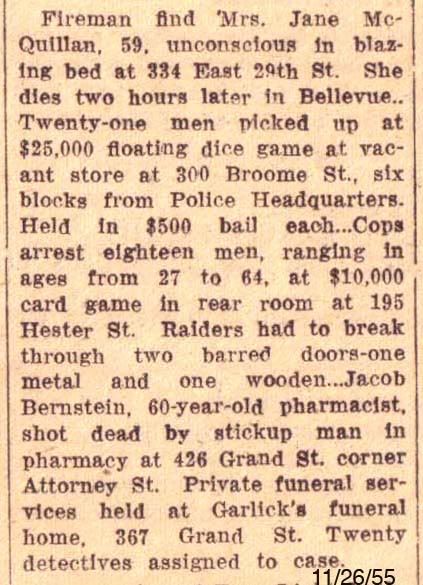

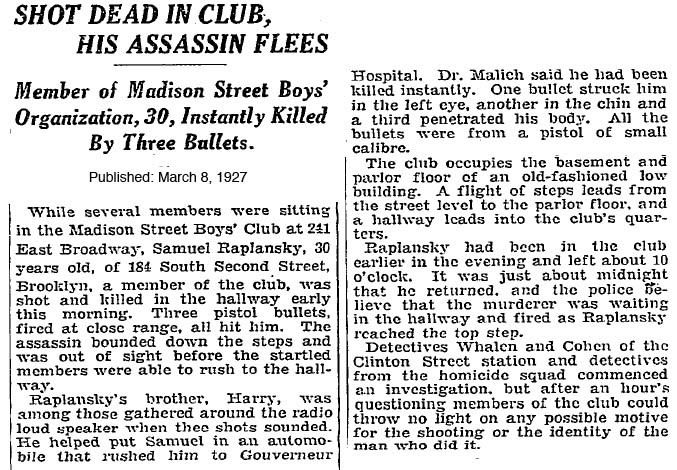

Interesting is that at this time the famous Epstein Twins, who were born on Market Street, just a few doors down from PS 177, were living at 245 East Broadway at this time. Was the murder later part of the plot for some of their screenplays? Did they belong to the Madison Street Club?

Interesting is that at this time the famous Epstein Twins, who were born on Market Street, just a few doors down from PS 177, were living at 245 East Broadway at this time. Was the murder later part of the plot for some of their screenplays? Did they belong to the Madison Street Club?