available from amazon

available from amazon and at the Washington Post's Book World

Reviewed by Jonathan Yardley :

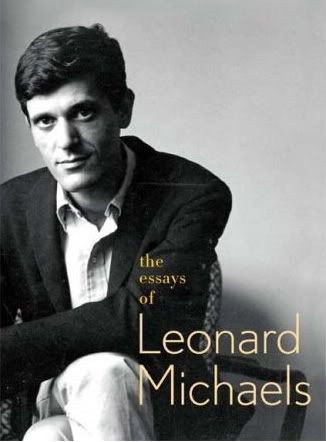

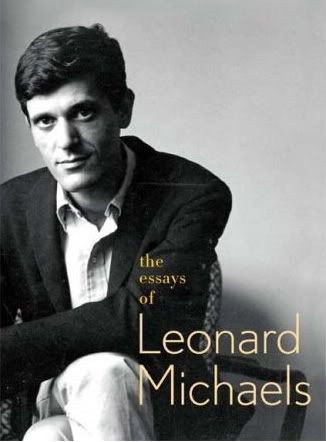

Leonard Michaels was a sublimely gifted prose stylist who died much too soon, in 2003 -- he had barely reached his 70th birthday but suffered from lymphoma -- and who left a slender but durable literary legacy. Primarily a writer of short stories, he made an improbable appearance on the bestseller lists in 1981 with his novel "The Men's Club," perhaps because it appeared at precisely the moment when its portrayal of male bonding coincided with feminist ridicule of male rituals. Such fame as that brought him was pretty much dashed five years later when the book was transformed into a dreadful movie, leaving Michaels feeling, as he says in one of the essays in this collection, "like a rape victim who not only suffers the opinions of cops but also feels guilty." That wry, self-mocking comment is typical of Michaels the writer, as it was of Michaels the man. At almost exactly the time that "The Men's Club" was published, I came to know him slightly -- he was teaching at Johns Hopkins, and I was living in Baltimore -- and to like him a great deal. In 1984 I served as chairman of the fiction jury for the newly revived National Book Awards and, hoping to have a jury whose members would have literary tastes diametrically opposed to my own, asked Michaels and Laurie Colwin to serve with me. No one was more surprised than I when we agreed, immediately and unanimously, to give the award to the unknown Ellen Gilchrist for her second book of stories, "Victory over Japan." To the best of my recollection, I never spoke or wrote to Michaels thereafter, but I remembered him with pleasure and was shocked by his death, just as I had been by Colwin's even more sudden and premature death in 1992. So I have been delighted to see his publisher bringing out his work in new editions over the past three years, first "The Collected Stories of Leonard Michaels" (2007) and now his collected essays. This is a considerably leaner book than the collected stories, but it packs a lot of punch and is filled, as was all his work, with sentences that border on poetry. If it is true that, as years ago someone said, Gore Vidal (as essayist) writes in perfectly shaped paragraphs, it is equally true that Leonard Michaels writes in perfectly shaped sentences. This would be cause for admiration and celebration in any writer, but surely it is far more so for one who did not begin to speak English until he was 5 years old. His parents immigrated from Poland to Manhattan's Lower East Side only steps ahead of the Holocaust -- "When the Nazis seized Brest Litovsk, my grandfather, grandmother, and their youngest daughter, my mother's sister, were buried in a pit with others" -- and in their tiny apartment the language spoken was Yiddish. That, and Jewishness, permeate his writing, as no one knew more keenly than he did: "Eventually I learned to speak English, then to imitate thinking as it transpires among English speakers. To some extent, my intuitions and my expression of thoughts remain basically Yiddish. . . . This moment, writing in English, I wonder about the Yiddish undercurrent. If I listen, I can almost hear it: 'This moment' -- a stress followed by two neutral syllables -- introduces a thought that hangs like a herring in the weary droop of 'writing in English,' and then comes the announcement, 'I wonder about the Yiddish undercurrent.' The sentence ends in a shrug. Maybe I hear the Yiddish undercurrent, maybe I don't. The sentence could have been written by anyone who knows English, but it probably would not have been written by a well-bred Gentile. It has too much drama, and might even be disturbing, like music in a restaurant or elevator. The sentence obliges you to abide in its staggered flow, as if what I meant were inextricable from my feelings and required a lyrical note. There is a kind of enforced intimacy with the reader. A Jewish kind, I suppose. In Sean O'Casey's lovelier prose you hear an Irish kind." Michaels said his literary influences included Franz Kafka, Lord Byron and Wallace Stevens (this last is frequently quoted in these essays), but reading that paragraph one can't help thinking that as a young man in the 1950s he must have spent a lot of time listening to Mort Sahl, Lenny Bruce and the other great Jewish comedians of the day, as his own comic voice and timing bear more than passing resemblance to theirs. In another essay, "A Sentimental Memoir," he recalls being "saved" as a young man by a professor of English at the University of Michigan named Austin Warren, and then he meanders into an account of falling "insanely in love" (which seems to have been a strong predilection with him) with a girl in Warren's class: "The girl had a slender boyish figure and blondish hair. I thought nobody but me considered her striking or had noticed the subtle perfection of her beautiful face. When I told my friend Julian that the most beautiful girl in Michigan was in Warren's class, he named her. He told me that she modeled naked for art students, she had a horrible reputation for licentiousness, everybody knew who she was, and that he was in love with her too. I decided that I was ready to forgive her everything. To forgive a girl was a very popular sentiment of the day. There were plays, novels, and movies about forgiving bad girls. As for the girl I was ready to forgive, I now suppose there were a couple of hundred other men who were forgiving her at the same time, all of us subject to a sort of spiritual narcissism that has long since gone out of the world. Too bad, I think, since it had extraordinary intensity and made a man feel tortured by goodness, which is a very high order of feeling." The phrasing ("tortured by goodness") and timing of that paragraph are absolutely perfect, and it points to a recurrent theme in these essays, not merely the autobiographical ones but also the critical ones about books, art and movies. Michaels certainly was no sentimentalist, but he strongly preferred the more modest, introspective, feeling culture of his youth to the arrogant, assertive, rude one of the present. Writing about the paintings of Edward Hopper, he gets to the point: "We rap, we shriek in the raving crowd, and wear clothing big enough to hold two or three people, and walk about wearing earphones, or talking into cell phones, lest we feel alone. There are no philosophers. In Hopper's day we wore tight clothing and held each other close, saying nothing, dancing slowly, shuffling a few inches this way and that, feeling possessed, possessed by feeling. People preferred feeling to sex." And, a few pages later: "There used to be obscenity. There used to be a distinction, as between day and night, between private and public. There used to be privacy." These are not the maunderings of one seized by nostalgia, but ones of an acutely sensitive man who was appalled by the coarsening of what now passes for adult civilization. As it happens this is a horror that I feel myself, which doubtless predisposes me to these essays, but what really matters is that you'll look for a long time to find writing as good as this and thinking as clear.

available from amazon and at the Washington Post's Book World Reviewed by Jonathan Yardley :

available from amazon and at the Washington Post's Book World Reviewed by Jonathan Yardley :

No comments:

Post a Comment