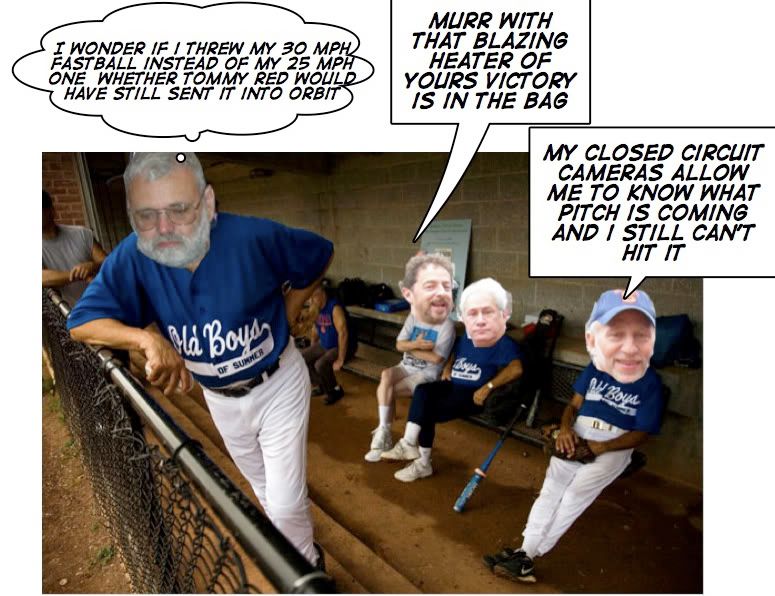

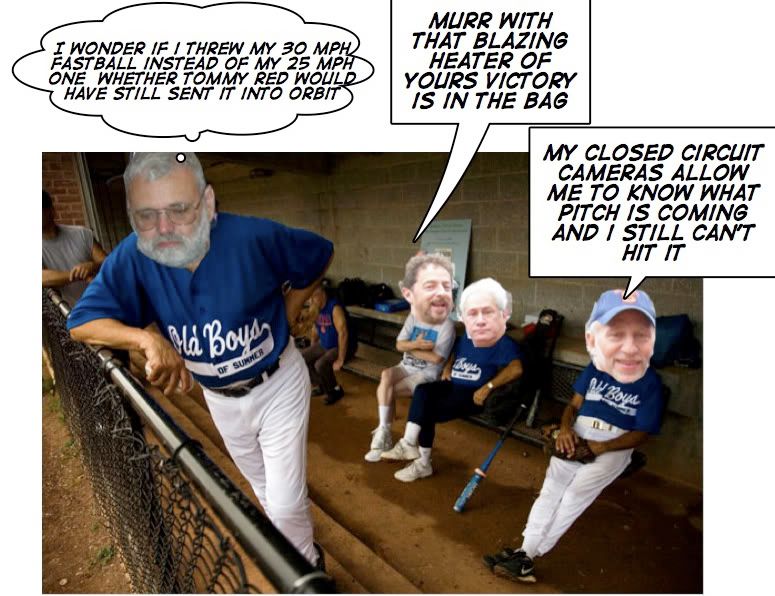

The Old (LMRC) Boys Of Summer

From the nytimes 8/7/09, with altered photos:

Still Boys at Play on a Field They Love, By JAVIER C. HERNANDEZ

The Old Boys of Summer, as they call themselves, trailed by seven runs in the seventh inning. As they readied for their final at-bats, looking for an improbable rally, pills for heart ailments were in the dugout, just in case. Each hitter planted his feet in the dirt, grumbling while trying to keep creaky bodies loose.

Tony Famular, 75, gripped his bat tightly, knocked the ball to the right side of the field and began his arduous dash to first base. The pitcher fielded the ball and threw him out at first for the final out of the game.

At the Prospect Park Parade Ground on Wednesday, the Old Boys played their annual ballgame against staff members of the Brooklyn Cyclones, a minor league affiliate of the New York Mets. For many of them, it has been a half-century since they took their first swings at the fields, a cradle of Brooklyn baseball that has been a training ground for the likes of Joe Torre, Sandy Koufax and Shawon Dunston, to name a few.

The players were a little grayer, a little slower and a little less optimistic about the future of their sport. But this was their diamond, the field where they spent many of their childhood summer days — and all they wanted was victory.

“This is what I live to do now,” Mr. Famular said. “It all started here.”

Growing up in Brooklyn, Mr. Famular said, he and his friends played baseball and its variants — stickball, slapball, punchball, stoopball, boxball — in the streets.

“Everyone talked baseball all the time,” he said, standing near the pitcher’s mound after the game.

He used to ride his bicycle the four miles from his house to play on the Parade Ground. Back then, the diamonds were so crowded that fields would overlap and they had to be reserved in advance. Today, the veteran players said, the park is much different.

“The kids today have too many options to have fun,” Mr. Famular said. “Whatever we saw in baseball, they don’t see.”

The Old Boys, many of whom did not know one another until they started playing together in 1995, practice once a week and try to schedule at least four games each year. Their ages range from 60 to 76.

During the fourth inning, the Old Boys manager, Andrew P. Mele, 69, went to bat. Mr. Mele has written a book, “The Boys of Brooklyn,” a history of the Parade Ground, which came out in May. The fields opened in 1869 and had by 1930 become the place to see new baseball talent, attracting crowds of more than 20,000, according to Mr. Mele’s book.

“It was a place where there was always a lot of activity going on,” Mr. Mele said. “It was something you always looked forward to. It was our life.”

Mr. Mele estimated that 40 Parade Ground graduates have earned World Series rings. As Mr. Mele, No. 7, hit a ball into right field, an old friend from the bleachers cried out.

“There you go!” shouted Gil Bassetti, who used to play against Mr. Mele as a pitcher for the Brooklyn Bisons, once a Kiwanis League team. Mr. Bassetti, 74, later became a professional baseball player and is now a part-time scout for the Baltimore Orioles. “That’s exactly the way he hit when he was young,” he told other spectators.

The Bisons’ former manager, Clarence L. Irving, sat in the bleachers cheering some of his former players. Mr. Irving, 83, recited the year-by-year history of the Bisons, reliving the championships that his team had won in the 1950s.

He said that being on the field again and seeing how his former players had embarked on diverse career paths — law, marketing, major league baseball — brought him a sense of pride.

“They are role models and the most generous of people,” Mr. Irving said.

Halfway through the game, as the Cyclones tallied up their runs (they ultimately secured an 8-1 victory), an Old Boys player, Frank Chiarello, took a moment in front of his fellow players to gripe about youthful energy.

“Life stinks,” he joked. “I hate young guys. I hate every guy on that team.”

Mr. Chiarello, a retired police officer, remembered his days as a centerfielder who would play until sunset. One day in the late 1950s, his wife came to the field to remind him they had a wedding to attend. He decided to skip it. “I’m going to finish the game,” he told her.

Mr. Chiarello said the team had developed a special camaraderie because of a shared history on the fields of Brooklyn.

“I learned how to make friends,” he said. “I learned how to be a human.”

Now that his vision is failing, Mr. Chiarello has trouble tracking the ball. Other team members said that they could still summon the strength for a powerful hit, but that running could be difficult.

“As long as we can stand up for a little bit longer,” Mr. Mele said, “we’ll keep doing it.”

No comments:

Post a Comment