It wasn't so sweet. The city was in the middle of a polio epidemic and Solomon Grunberg of 167 Orchard Street was a victim.

It wasn't so sweet. The city was in the middle of a polio epidemic and Solomon Grunberg of 167 Orchard Street was a victim.about that epidemic from the University of Mary Washington

Polio Epidemic of 1916

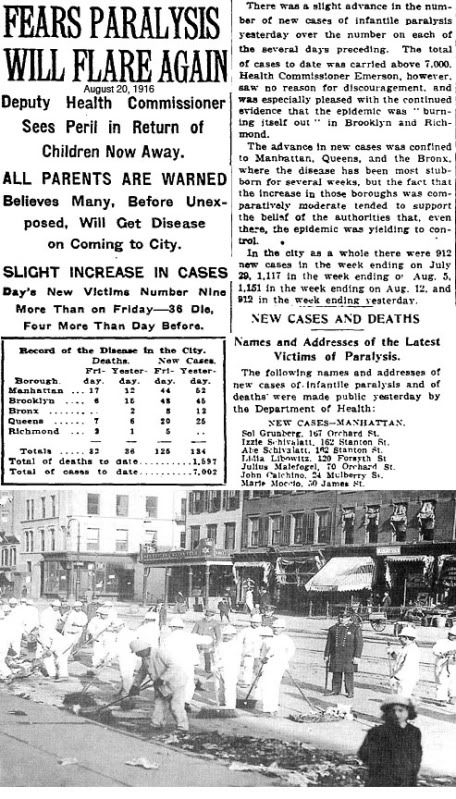

Although polio has sporadically plagued the earth for thousands of years, isolated cases did not show up in the United States until the late nineteenth century. Even then, it was considered a "medical rarity" as doctors spanned entire careers without seeing a single case of polio. However, this changed in 1916 when the first polio epidemic hit the United States, killing and crippling thousands of Americans.

The polio epidemic of the summer of 1916 appears to have begun in Brooklyn, New York when a limited number of children awoke one morning unable to move their arms or their legs. Desperate, their parents rushed the stricken children to neighborhood health stations, but the doctors and nurses were puzzled by the various symptoms. As the days passed, the cases continued to steadily increase. By the end of June, the professionals finally recognized that they were facing an epidemic of infantile paralysis or polio. But, the doctors could not explain it, accurately diagnosis it, treat it, or prevent it--circumstances that enhanced the public's fear and uncertainty, especially since most Americans in the early twentieth century believed that they were living in a new age of science and medicine. As the disease spread, and doctors could not provide effective help or knowledgeable answers, many Americans concurred with one Philadelphian who wrote that "the ignorance of the medical profession in this instance is appalling, and is quite sufficient to cause lack of confidence and distrust toward the whole profession."

Out of confusion and lack of control and understanding of polio, scientists turned to the usual scapegoats of disease and epidemics in America: immigrants and their slums. However, this explanation was not tied solely to rampant nativist sentiments of the early twentieth century; it was based also in the Progressive Era's emphasis on sanitation and hygiene. Scientists and medical professionals claimed that the simple explanation for the spread of polio was the apparent filth and overcrowding of the immigrant neighborhoods. The disease then reached the middle- and upper-classes through direct contact, flies, or animals like cats and dogs.

Ironically, as scientists eventually would come to understand, polio was, according to polio historian Jane Smith, an "inadvertent by-product of modern sanitary conditions." As a result of public sanitation efforts and closed sewer systems, Americans had a dramatically decreased possibility of being exposed to the polio virus as infants, resulting in non-immunity for children and adults. Thus, polio defied traditional demographics of disease. It struck blacks, immigrants, and native Americans whether urban, suburban, or rural, clean or dirty, rich or poor, and young or old (although the largest percentage of cases were elementary school-age children). By December of 1916, the polio epidemic had spread from New York City to twenty-seven states along the eastern seaboard and into the mid-west. Over the course of seven months, out of twenty-seven thousand reported cases of polio, six thousand people had died, and thousands more would be paralyzed or deformed for the rest of their lives. After 1916, the United States did not escape a single summer without an epidemic, although some years were far worse than others.

No comments:

Post a Comment