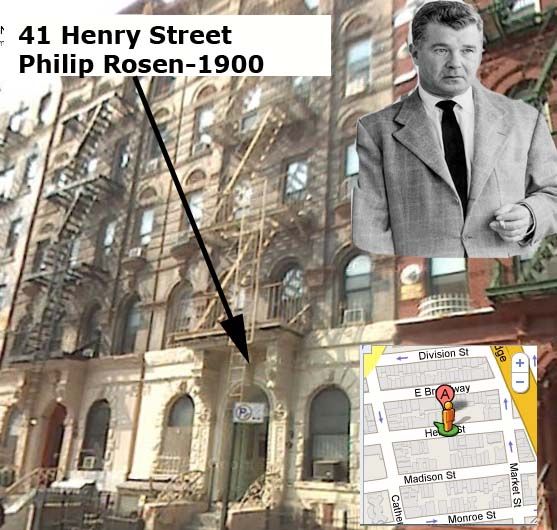

Two biographies. The second led me to possibly find Robert's father Philip (knowing the real name was Rosen) either living here in 1900 or on 45 Eldridge Street. Philip Rosen is the only Rosen to give birth to a Robert Rosen in 1908.

Two biographies. The second led me to possibly find Robert's father Philip (knowing the real name was Rosen) either living here in 1900 or on 45 Eldridge Street. Philip Rosen is the only Rosen to give birth to a Robert Rosen in 1908.Rossen's body of work is amazing

Robert Rossen (March 16, 1908 – February 18, 1966) was an American screenwriter, film director, and producer. In a film career that spanned almost three decades, Rossen was twice nominated for an Academy Award for best director and once for best adapted screenplay. Rossen was twice called before the House Un-American Activities Committee, in 1951 and again in 1953. He exercised his Fifth Amendment rights at his first appearance, refusing to state whether he had ever been a Communist. As a result he was was unofficially blacklisted by the Hollywood movie studio bosses. At his second appearance he named 57 people as current or former Communists and was removed from the unofficial blacklist. He returned to filmmaking, although his last film so disillusioned him that he did not work for the last three years of his life.

Rossen was born and raised on the lower East side of New York City, the son of a rabbi. In his youth he hustled pool and did some prizefighting. Rossen began his career on Broadway as a playwright and a stage manager.Rossen directed two plays in 1932, Steel by John Wexley and The Tree, an anti-lynching play by Richard Maibaum. Rossen directed Maibaum's Birthright, an anti-Nazi drama, in 1933. Rossen wrote and directed The Body Beautiful, a comedy about a naive burlesque dancer, in 1935. The play ran just four performances but Warner Bros. director Mervyn LeRoy was so impressed that he signed Rossen to a personal screenwriting contract. Rossen came to Hollywood in 1937.

Rossen's first solo script was for They Won't Forget, based on a fictionalized account of the Leo Frank case and featuring Lana Turner in her debut performance.

After ten years with Warner Bros. Rossen moved to Columbia Pictures. He wanted to direct and was given his opportunity with the 1947 film Johnny O'Clock. He followed this up the same year with Body and Soul, described as "possibly the best prizefight film ever made." His next film was All the King's Men (1949), described as Rossen's "triumph and very likely his corruption".The film, based on the novel of the same name by Robert Penn Warren, won the Academy Award for Best Picture; Broderick Crawford won the award for Best Actor and Mercedes McCambridge was honored as Best Supporting Actress. Rossen was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Director but lost to Joseph L. Mankiewicz and A Letter to Three Wives. He won a Golden Globe for Best Director and the film won the award for Best Picture. Rossen joined the American Communist Party in 1937. He left the party in 1947. He joined, he would later tell his son Stephen, because he believed the party was “dedicated to social causes of the sort that we as poor Jews from New York were interested in." Rossen was one of 19 "unfriendly witnesses" subpoenaed in October 1947 by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) during the second Red Scare but ultimately was one of eight not called to testify. Rossen in 1948 sent a letter to Columbia Pictures chief Harry Cohn advising Cohn that he was not at that time a Communist. In 1951, however, Rossen was named as a Communist by several HUAC witnesses and he appeared before HUAC for the first time in June of that year. He testified that he was not a member of the Communist Party and that he disagreed with the aims of the party but when asked to state whether he had ever been a member of the party Rossen took what came to be known as the "augmented Fifth" and refused to answer. In May 1953, Rossen again appeared before the committee and named 57 people as Communists. He explained to the committee why he chose to testify: "I don't think, after two years of thinking, that any one individual can indulge himself in the luxury of personal morality or pit it against what I feel today very strongly is the security and safety of this nation." Stephen Rossen later shed light on his father's decision:

"It killed him not to work. He was torn between his desire to work and his desire not to talk, and he didn't know what to do. What I think he wanted to know was, what would I think of him if he talked? He didn't say it in that way, though. Then he explained to me the politics of it—how the studios were in on it, and there was never any chance of his working. He was under pressure, he was sick, his diabetes was bad, and he was drinking. By this time I understood that he had refused to talk before and had done his time, from my point of view. What could any kid say at that point? You say, 'I love you and I'm behind you.'"

Having testified before HUAC and having been removed from the unofficial blacklist, Rossen returned to producing and directing with Mambo (1954), followed by Alexander the Great (1956). In 1961, Rossen co-wrote, produced and directed The Hustler. Drawing upon his own experiences as a pool hustler, Rossen teamed with Sidney Carroll to adapt the novel of the same name for the screen. The Hustler was nominated for nine Academy Awards and won two. Rossen was nominated as Best Director and with Carroll for Best Adapted Screenplay but did not win either award. He was named Best Director by the New York Film Critics Circle and shared with Carroll the Writers Guild of America Award for Best Written Drama. The Hustler was an enormous popular success and is credited with sparking a resurgence in the popularity of pool in the United States, which had been on the decline for decades.

Following his final film, Lilith (1964), Rossen lost interest in directing, reportedly because of conflicts with Lilith star Warren Beatty. "It isn't worth that kind of grief. I won't take it any more. I have nothing to say on the screen right now. Even if I never make another picture, I've got The Hustler on my record. I'm content to let that one stand for me."

Robert Rossen died at age 57 following a series of illnesses and is interred at Westchester Hills Cemetery in Hastings-on-Hudson, New York. He was survived by his wife Sue, daughters Carol and Ellen and son Stephen.

No comments:

Post a Comment