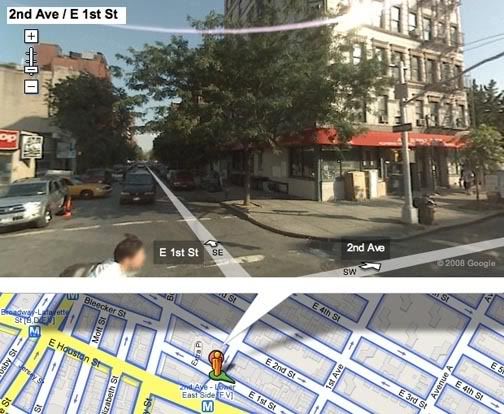

In the interview, Polonsky mentioned that the family moved to Manhattan in the late 1920's so his father could be closer to his pharmacy on East 1st and 2nd Avenue. It's possible this might be the store (actually it's the only one left on any of the for corners of that intersection). Polonsky lived in an Italian section of the East Village on 16th Street. But wait, I had completely forgotten about a much more concrete link to KV. Back in November 2007 there was a posting about Abraham Polonsky's son Hank. Hank worked on the production of Bananas and his sister Susan married former KVer Sherwood Epstein whose father was an owner of Normandie Pharmacy on Catherine and Monroe. Whew!

Abraham Polonsky's obituary from the latimes

Hollywood Blacklist’s Abraham Polonsky Dies, By Myrna Oliver, October 28, 1999 Abraham Polonsky, a blacklisted Hollywood screenwriter and director who continued his creative output without credit for two decades during the anti-Communist era, has died. He was 88. Polonsky, who scripted and directed such films as “Force of Evil” and “Tell Them Willie Boy Is Here,” died Tuesday at his Beverly Hills home after suffering a massive heart attack. His film credits numbered a scant nine, but Polonsky remained highly respected in Hollywood for his work as well as for his refusal to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee on his flirtations with communism.

The eclectic Polonsky wrote not only screenplays, but also five novels, top-quality radio and television scripts, essays and even legal briefs during his short stint as a lawyer. An American wartime spy whose full name was Abraham Lincoln Polonsky, he was in many ways an odd target for the blacklist. When Polonsky first decided to write after practicing law and teaching English at what is now City University of New York, he scripted radio dramas for Orson Welles and wrote novels. He didn’t need Hollywood.

But he decided that being a filmmaker would provide an excellent cover for his wartime work in Europe with the Office of Special Services, the forerunner of the CIA. Besides, he told The Times in 1970, American servicemen in World War II were guaranteed the same jobs they left, and he liked the idea of a $450 weekly screenwriter’s pay waiting for him. After a debut credit for collaboration on the script for “Golden Earrings” in 1947, Polonsky found real success with the John Garfield boxing film “Body and Soul.” That script netted him an Oscar nomination and a contract from Garfield to co-write and direct “Force of Evil” in 1948. Critic Andrew Sarris described that film noir, starring Garfield as a racketeer’s lawyer, as “one of the great films of the modern American cinema.” But Polonsky was to have only one more writing credit, for “I Can Get It for You Wholesale” in 1951, before politics intervened. The promising new director would not direct again for 21 years until “Tell Them Willie Boy Is Here” starring Robert Redford in 1969. When the Un-American Activities Committee convened in 1947, 10 of those subpoenaed refused to discuss Communist Party affiliations or name party members. Dubbed the Hollywood 10, they were held in contempt of Congress, fired from their jobs and imprisoned.

Polonsky, who had been a member of the Communist Party, was subpoenaed for a new round of hearings in 1951 in Hollywood. He refused to testify, and Rep. Harold Velde called him the “most dangerous man in America.” Polonsky was fired from 20th Century Fox and had to leave Hollywood–and the movie business–to get work. “If you said you were sorry you were a radical and had seen the errors of your ways, you were let off. That’s like saying you have no right to make political experiments in your mind,” Polonsky told The Times in 1968 when he returned to directing. “That’s the kind of thing they do in Communist countries, but we’re supposed to be a free country. We need to be a genuinely free country and not merely pretend to be one.” Polonsky more than made a living–even increasing his earnings, he often said with a chuckle–by writing such television shows as “You Are There” and the series “Danger.” In 1956, he also wrote one of his five novels, “A Season of Fear,” featuring not a screenwriter but a Los Angeles Department of Water and Power civil engineer imperiled by anti-communist zeal.

Never completely abandoning Hollywood, the outcast Polonsky co-wrote the 1959 film “Odds Against Tomorrow,” the writing of which was attributed to John O. Killens. Later a leader in the fight to have credits restored to blacklisted filmmakers, Polonsky earned his own credit for that screenplay in 1996 from the Writers Guild of America.

Remarkably unembittered by his experience, the easygoing Polonsky said philosophically in 1996: “Everything in life has its fundamental lack of charm.” But Polonsky was not charitable toward colleagues who had testified and named names (including his) in the 1950s. Although he taught in recent years at USC’s School of Cinema-Television at the same time as motion picture composer David Raksin taught in its School of Music, Polonsky pointedly refused to speak to him. Raksin had admitted having been a Communist and named 13 others in testimony before the Un-American Activities Committee.

And when the Academy of Motion Pictures set out to award director Elia Kazan its lifetime achievement Oscar earlier this year, Polonsky said: “I’ll be watching, hoping someone shoots him.” Polonsky told The Times he was willing to forgive anybody other than Kazan who apologized for testifying to the committee. “But Kazan,” he said, “didn’t just betray his friends. He took out an ad in the New York Times. He elected himself the head of the opposition. He acted like a big shot. I admit I’m prejudiced. He’s a creep. I wouldn’t say hello to him if he came across the street.”

Earlier this year, Polonsky was honored, along with screenwriter Julius Epstein, with the career achievement award of the Los Angeles Film Critics Assn. In the 1990s, Polonsky helped write the McCarthy-era docudrama “Guilty by Suspicion” and appeared around the country in programs observing the anniversary of the blacklist. His USC film course dealt with philosophy and was titled “Consciousness and Content.”

As a novelist, something he aspired to become in his youth, Polonsky published his first effort in 1940–“The Goose Is Cooked,” co-written with Mitchell A. Wilson under the joint pseudonym Emmett Hogarth. In addition to “A Season of Fear,” his other novels were “The Enemy Sea” in 1943, “The World Above” in 1951 and “Zenia’s Way” in 1980. Polonsky was married to Sylvia Marrow from 1937 until her death in 1993. He is survived by his wife, Iris; his son, Hank; and two granddaughters. For the record Polonsky obituary–The obituary of director and screenwriter Abraham Polonsky in Thursday’s Times contained an incorrect listing of survivors. He is survived by his son, Hank Polonsky, and a daughter, Susan Epstein. In the same obituary, a reference to OSS was incorrect. It stands for Office of Strategic Services. ↩

No comments:

Post a Comment