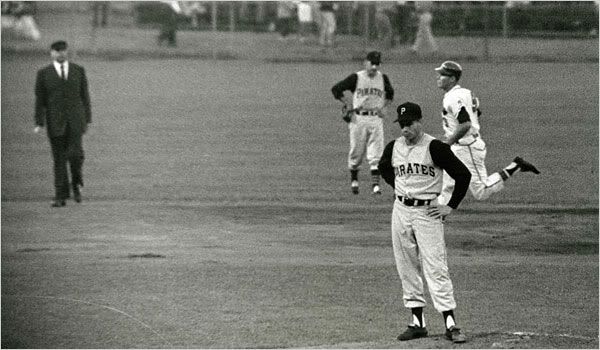

an excerpt from the nytimes of May 24th 2009 The 1959 LMRC team certainly remember this game.

Linked to Haddix’s Perfection by Western Union Ticker Tape, By GERALD ESKENAZI. The ticker tape in the bell jar began to click.

It was May 26, 1959, my first night at The New York Times. I was a $38-a-week copy boy.

I knew that Western Union ticker was important — it was the sports department’s lifeline to baseball games that were increasingly being played at night. Why, they were even playing on the West Coast now.

The yellow ribbon unfurled out of the jar. Usually, it gave bare information, a line score. This time, it read, in shorthand, as I recall: “Harvey Haddix Pittsburgh Pirates pitching perfect game through eight innings.”

Wow! What a business, I thought. What a way to start what was to be a sportswriting career with the paper for more than 40 years.

The game was in Milwaukee, another place that symbolized baseball’s break with its longtime franchise cities. But for me, baseball life, a part of my soul, had ended when the Dodgers left Brooklyn only a couple of years earlier. Here I was, a budding sportswriter, yet disenchanted with the American pastime. Oh, sure, I knew about the Columbia University cultural historian Jacques Barzun’s famous claim, “Whoever wants to know the heart and mind of America had better learn baseball.”

I had come in to work at 7 that night — I was on the 7 p.m. to 3 a.m. shift. But some of the other copy boys had whispered to me that you never had to stay that late, that usually you’d get a slide, be out by 2 in the morning. Even with stuff going on in the West Coast, nothing happened that late at night.

I watched what the other copy boys did: They brought the editors on the copy desk coffee. Like them, I tore off the stories from the Associated Press and the United Press machines. I took the “copy,” the edited stories that the head desk man gave me, and I rolled them up, put them in a plastic tube and sent it up the pneumatic tube toward the composing room. I went up to the composing room for the first edition, a noisy place clanging with metal, where men had ink on their fingers, where Linotype machines from the 1890s were going through some convoluted mechanics to punch out six metal words a minute.

Meanwhile, halfway across America, Haddix, the Kitten, was mowing them down, playing by the same rules they had played by for all the 20th century — 60 feet 6 inches from home, three strikes and you’re out — while I was part of an operation that, similarly, was unchanged over that course of time.

The ticker continued clacking: nine innings, no base runners; 10 innings; 11 innings; 12 innings! No one in the history of baseball had ever had such a performance, and I was there, tethered to the game through Western Union ticker tape.

No comments:

Post a Comment